The effects of overstory mortality on snow accumulation and ablation

Mountain pine beetles have killed a large percentage of mature lodgepole pine trees over an area of more than 14 million hectares in the B.C. Interior. Research has shown that this can increase the magnitude of spring runoff (Uunila et al., 2006).

On this page

- Project overview

- Project objectives

- Monitoring activities

- Publications

- References and additional resources

Project overview

Forest licensees are also permitted to log beetle-attacked pine stands at an accelerated rate. The net effect is that most of B.C.’s mature pine stands will be changing rapidly over the next decades due to deterioration of the overstory, natural regeneration, clearcut harvesting, and managed reforestation.

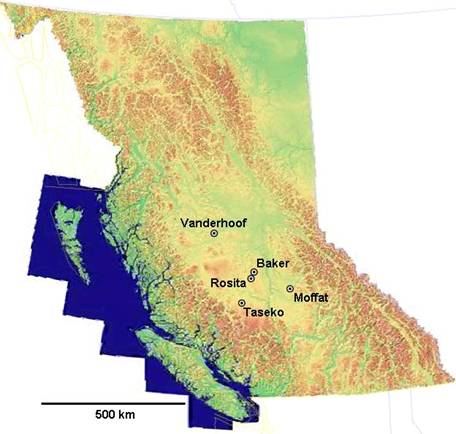

This project documents differences in structure between pine stands at different stages of growth and deterioration, changes within stands over time, and the effects of those differences on snow hydrology at the stand level. This will help watershed modellers predict possible changes in stream flow due to pine beetles and forest management. The map shows the locations of five study areas where this work is being done.

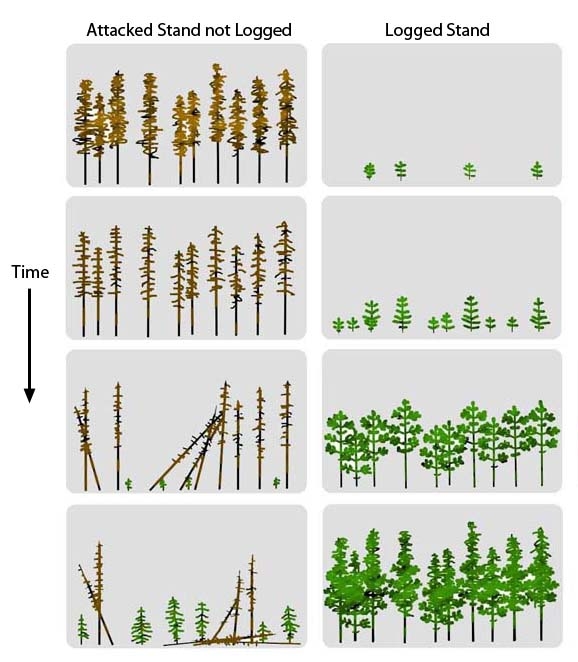

The following shows a conceptual model of how a beetle-attacked pine stand might change over several decades if it were left to develop naturally versus how it would be expected to change if it were logged and reforested.

This is a photo of a stand in which the mature lodgepole pine trees were killed about 20 years earlier. The dead trees have fallen and the site is recovering naturally due to pine and spruce that established both before and after beetle attack. This stage of development corresponds with the fourth frame from the top in the left-hand side of the figure above.

Project objectives

Resource managers are concerned about hydrologic changes due to beetle-related stand deterioration, as well as accelerated timber harvesting for the purpose of utilizing the affected timber before it deteriorates.

When pine trees die and deteriorate, more snow and rain reach the ground and less soil moisture is removed by transpiration. This can lead to wetter soils and increased runoff. However, dead trees still intercept some precipitation and eventually, the forest will regenerate. Clearcut harvesting also reduces interception and transpiration but the effects are greater and occur faster than those associated with overstory mortality. On the other hand, forest regeneration on a clearcut is faster than that in a beetle-killed stand. We need to quantify the magnitudes of hydrologic changes due to beetles versus logging and the different rates of recovery after those changes.

In order to make watershed management decisions, managers need professional advice on the expected hydrologic effects of pine beetles and logging under different scenarios. The quality of such advice can be improved with the application of a watershed runoff model that accurately represents what is happening at the stand-level.

This project is improving our understanding of stand-level processes by quantifying snow hydrology and stand characteristics in natural and managed pine stands at different stages of deterioration and recovery. Each study area has at least five plots including one in a recent clearcut, at least one in a partially-recovered clearcut, and at least three in natural pine stands. The Rosita and Vanderhoof study areas also include immature natural pine stands recovering from wildfire. The Rosita study area includes two stands that were severely attacked by beetles in the early 1980s. Differences in snow accumulation and ablation are being compared with stand properties derived from tree surveys, ground-based canopy photography, and high-resolution aerial photography.

Monitoring activities

A total of 29 plots in 5 study areas were monitored from 2006 to 2008. Snow storage and ablation rates were documented in each plot for three years. Vegetation and coarse woody debris were surveyed in 2007. A variety of radiation parameters have been calculated from fisheye canopy photos taken in the summers of 2006 and 2008. Aerial photography has been used to document rates of snow disappearance, stand structure, and changes in stand structure over time.

The effects of plot characteristics on snow hydrology have been described in the following publications.

Publications

Redding, T., R. Winkler, P. Teti, D. Spittlehouse, S. Boon, J. Rex, S. Dubé, R.D. Moore, A. Wei, M. Carver, M. Schnorbus, L. Reese-Hansen, and S. Chatwin. 2008. Mountain pine beetle and watershed hydrology. In Mountain Pine Beetle: From Lessons Learned to Community-based Solutions Conference Proceedings, June 10–11, 2008. BC Journal of Ecosystems and Management 9(3):33–50.

Teti, P., 2008. Effects of overstory mortality on snow accumulation and ablation. Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Pacific Forestry Centre, Victoria, BC. Mountain Pine Beetle Working Paper 2008-13. 34 p.

Teti, P. 2009 (in press). Effects of mountain pine beetles and timber harvesting on stand attributes and snow on the B.C. Interior Plateau. Proceedings of the 77th Western Snow Conference, Canmore, Alberta.

Teti, P. and R. Winkler. 2008. Snow hydrology and solar radiation in growing and deteriorating pine stands. In Mountain Pine Beetle: From Lessons Learned to Community-based Solutions Conference Proceedings, June 10–11, 2008. BC Journal of Ecosystems and Management 9(3):136–138.

References and additional resources

The Upper Penticton Creek Watershed Experiment (PDF, 875KB)

Uunila, L., B. Guy, and R. Pike. 2006. Hydrologic effects of mountain pine beetle in the interior pine forests of British Columbia: Key questions and current knowledge. BC Journal of Ecosystems and Management 7(2):37-39.

Winkler, R. and J. Roach. 2005. Snow accumulation in B.C.’s Southern Interior forests. Streamline Watershed Management Bulletin 9(1):1-5.