Part 4: RoadSafetyBC’s Driver Medical Fitness Manual Appendices

The table below describes the classes of B.C. driver licences.

- Semi-trailer trucks and all other motor vehicles or combinations of vehicles except motorcycles

- Buses, including school buses, special activity buses and special vehicles

- Trailers or towed vehicles may not exceed 4,600 kilograms except if the bus and trailers or towed vehicles do not have air brakes

- Any motor vehicle or combination of vehicles in Class 4

- Trucks with more than two axles, such as dump trucks and large tow trucks, but not including a bus that is being used to transport passengers

- Trailers may not exceed 4,600 kilograms except if the truck and trailers do not have air brakes

- A tow car towing a vehicle of any weight

- A mobile truck crane

- Any motor vehicle or combination of vehicles in Class 5

- Buses with a maximum seating capacity of 25 persons (including the driver), including school buses, special activity buses and special vehicles used to transport people with disabilities

- Taxis and limousines

- Ambulances

- Any motor vehicle or combination of vehicles in Class 5

- Taxis and limousines (up to 10 persons including the driver)

- Ambulances

- Special vehicles with a seating capacity of not more than 10 persons (including the driver) used to transport people with disabilities

- Any motor vehicle or combination of vehicles in Class 5

- Two axle vehicles including cars, vans, trucks and tow trucks

- Trailers or towed vehicles may not exceed 4,600 kilograms

- Motor homes (including those with more than two axles)

- Limited speed motorcycles and all-terrain vehicles (ATVs)

- Passenger vehicles used as school buses with seating capacity of not more than 10 persons (including the driver)

- Construction vehicles

- Three-wheeled vehicles - does not include three-wheeled motorcycles (trikes) or motorcycle/sidecar combinations

- Does not include Class 4 vehicles or motorcycles

- Motorcycles, all-terrain cycles, all-terrain vehicles (ATVs)

- Trailers or towed vehicles exceeding 4,600 kilograms provided neither the truck nor trailer has air brakes

- Any motor vehicle or combination of vehicles in Class 5

- Recreational (house) trailers exceeding 4,600 kilograms provided neither the truck nor trailer has air brakes

- Any motor vehicle or combination of vehicles in Class 5

Effective April 1, 1992, the US Department of Transport required all American commercial drivers to hold an American Commercial Drivers Licence (CDL).

In preparation for this requirement, a reciprocity agreement between Canada and the US completed 1989. This ensured that commercial driver’s licences issued by Canadian provinces and territories under the National Safety Code Standards are recognised in the US. In fact, to ensure the one driver, one licence concept, the holder of a provincial or territorial commercial driver licence is prohibited from obtaining a CDL. The US Federal Register of Tuesday, May 23, 1989 proclaimed the Reciprocity Agreement.

Subsequently on December 30, 1998, Canada and the US signed reciprocity letters on medical fitness requirements for operators of commercial motor vehicles. The elements prescribed in the reciprocity agreement related to Canadian provinces and territories adhering to the National Safety Code (NSC) and that the licensing and testing standards were deemed equivalent to US standards. A similar evaluation by jurisdictions deemed the US CDL to be equivalent to the NSC.

Letters between the US and Canadian federal governments were used as the agreement, and when taken together constituted the understanding between Canada and the US respecting reciprocity of commercial driver licences.

By virtue of the agreement, the two countries medical standards were deemed equivalent with the exception of the requirements regarding (Cdn) (1) insulin-dependent diabetic drivers, (2) hearing impaired drivers, (3) drivers with epilepsy and (4) drivers operating under a medical waiver or who are operating under medical grandfather rights who are prohibited from operating in international commerce.

Both countries agreed to adopt a unique identifier code to be displayed on the licence and the driving record to identify a commercial driver who is not qualified or disqualified from operating a commercial vehicle in the other country.

In December 2001, CCMTA agreed the Canadian identifier would be “W”, and defined as: “restricted commercial class - Canada only”. In December 2008, FMCSA announced it will implement the identifier “V” which will indicate the US driver is only allowed to drive in the US and is not medically qualified to drive in Canada. The identifier “V” is scheduled for implementation on January 2014.

As part of the Canada – US agreement commercial drivers (Class 1, 2, 3 and 4 licence holders) are required to file a satisfactory medical report on application, every 5 years to age 45, at least every 3 years from age 46 to 65 and annually thereafter.

The relationship between BC driver fitness policy and the Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators (CCMTA) Medical Standards for Drivers

All Canadian provinces and territories have the authority to establish their own driver fitness policies. In order to support a consistent approach to driver fitness across the country, CCMTA publishes the Medical Standards for Drivers (formerly called the National Safety Code).

The CCMTA Medical Standards are developed by medical advisors and administrators from Canadian provincial driver licensing bodies. The standards are intended as a guide in establishing basic minimum medical qualifications to drive for both private and commercial drivers and are intended for use by both physicians and regulators.

Although no jurisdiction in Canada is required to adopt the CCMTA Medical Standards, the majority are adopted by the provincial and territorial motor vehicle licensing departments. This achieves a uniformity of standards across Canada.

The relationship between BC driver fitness policy for commercial drivers, the CCMTA Medical Standards and the North American Free Trade Agreement

Under the North American Free Trade Agreement, the United States and Canada reached agreement on reciprocity of the medical fitness requirements for drivers of commercial motor vehicles effective March 30, 1999. The countries determined that the medical provisions of U.S. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Regulations (FMCSRs) and - what was then - the Canadian National Safety Code (NSC) are equivalent.

The exception however is that Canadian drivers who are insulin-treated diabetics, who are hearing-impaired, or who have epilepsy are not be permitted to operate commercial motor vehicles (CMVs) in the United States. U.S. regulations prohibit individuals with those conditions from operating CMVs in the United States. They are allowed to drive commercial vehicles in Canada.

Because the reciprocal agreement between the United States and Canada identifies the CCMTA Medical Standards as the standard for commercial drivers, this means that BC commercial drivers must meet or exceed the CCMTA Medical Standards if they drive in the United States.

The driver fitness guidelines in this manual for commercial drivers who are insulin-treated diabetics, hearing-impaired, or who have epilepsy clearly state where the BC guidelines are different from the CCMTA Medical Standards for Drivers and the U.S. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Regulations (FMCSRs) and the implication for BC commercial drivers with these conditions who want to drive in the U.S.

About aging drivers

As with the general population in Canada, the driving population is aging. The functional declines associated with aging are well documented. These functional declines in healthy aging drivers are unlikely to lead to unsafe declines in driving performance, except in the case of extreme old age.

However, aging is also associated with increased risk for a broad range of medical conditions, such as visual impairments, musculoskeletal disorders, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cognitive impairment and dementia. These medical conditions and medications used to treat them may affect fitness to drive.

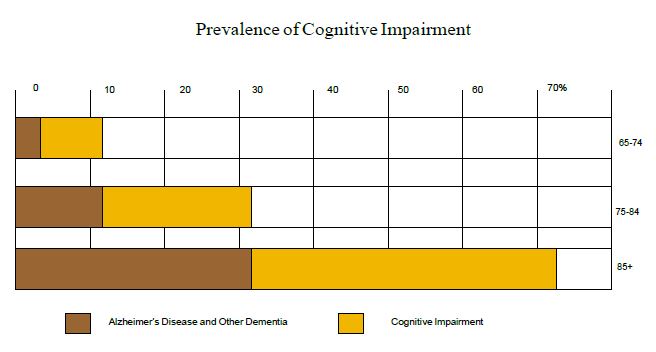

Although there are many age-associated medical conditions that may affect driving, there is a particularly strong association between cognitive impairment and dementia and impaired driving performance. A large, national population-based study done in Canada in 1991 showed that 25% of the population 65 and older have some form of cognitive impairment or dementia, rising to 70% for those 85 and older.

Demographics

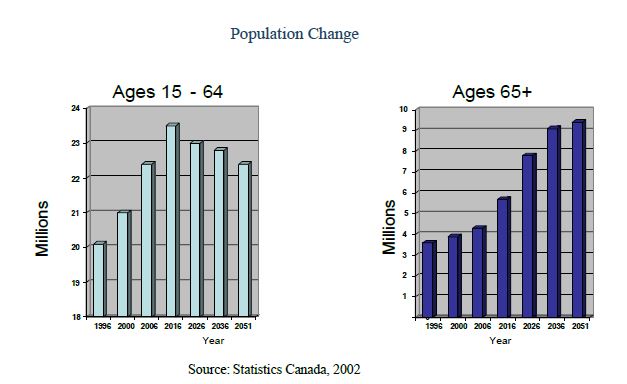

The number of people in Canada over the age of 65 increased from 3.5 million in 1996 to 4.2 million in 2006. By 2051, it is projected to be more than 9 million.

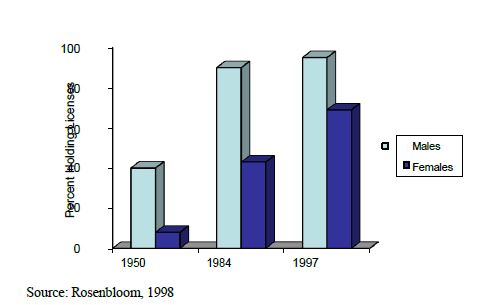

These increases are reflected in the driving population, with the percentage of drivers who are older increasing over time. Increases in the percentage of older women who have a driver’s licence will also have an impact. Currently, 50% of females over the age of 65 are licensed to drive; in 2031 it is projected to be 85%.

Aging and multiple medical conditions

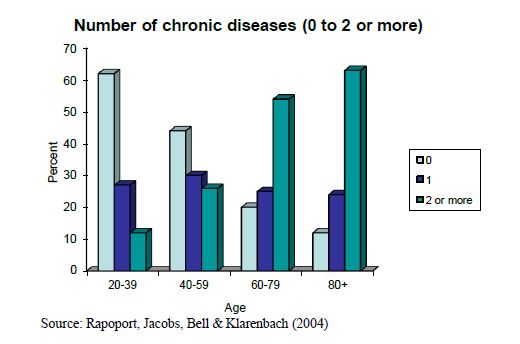

Because of the association between age and many chronic medical conditions, aging drivers are more likely to have one or more of these conditions. A 2003 survey found that 33% of Canadians age 65 and older had 3 or more chronic medical conditions, compared with 12% of younger adults. The survey also found that the average number of chronic conditions increases with age.

With an increased rate of multiple medical conditions, there is also a greater likelihood that aging drivers will be taking multiple medications (polypharmacy). With each additional medication taken, there is an increased risk of side effects and adverse interactions between medications, which may affect fitness to drive. While in many cases the adverse effects may be temporary or avoidable, where specific medications or dosages are required there may be a persistent impairment of the functions needed for driving.

Aging and adverse driving outcomes

As a group, older drivers are less likely to be involved in a crash than other age groups. However, the reason for this is that older drivers spend less time driving than others. When driving exposure is considered, older drivers show an increased crash risk, an increased risk for at-fault crash, and an increased risk of being injured and dying in a crash.

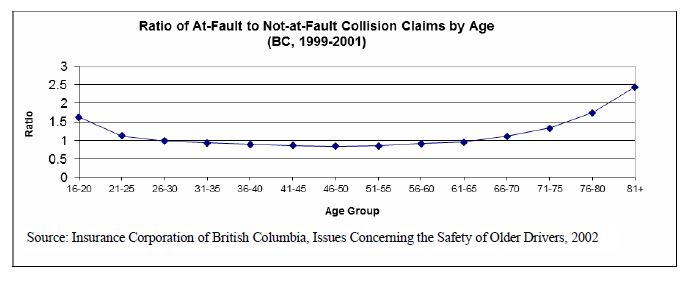

Statistics from ICBC indicate that older drivers are involved in a disproportionate number of at-fault crashes. The chart below shows the ratio of at-fault (50% liable) to not-at-fault crashes for different age groups. Drivers between the ages of 16 and 20 have more than 1.5 times the average at-fault versus not-at-fault crashes. Drivers in the 30 to 65 age group have a lower-than-average at-fault crash ratio. At about age 70, the ratio of at-fault crashes begins to rise, climbing to 2.5 for drivers who are 81 and older.

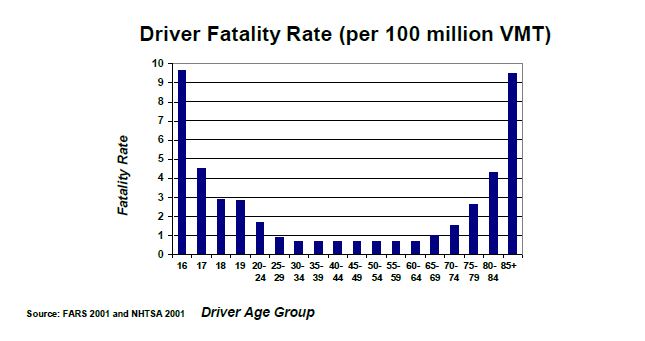

An examination of driver fatality rates, adjusted for driving exposure, indicates that there are two high risk age groups: ages 16 to 19 and 65 and older. Older drivers are also more likely to be injured in a crash and to incur more severe injuries than younger drivers. The higher injury and fatality rates of older drivers is, in part, attributable to an increased susceptibility of older people to injury and death.

Unlike younger driver crashes, most traffic fatalities involving older drivers occur during the day time, on week-days, and in safe road conditions, with the majority of the crashes involving another vehicle.