Memoirs of a Pioneer Probation Officer

In 1959, Royal Air Force veteran of World War II and former air gunner Peter Bone had served five years as a probation officer with Britain’s probation service and was looking for new challenges. He found them in British Columbia, where he was sworn in as the province’s 33rd probation officer. With his move from supervising “one square mile” in Bristol, England, to becoming the first probation officer in the 12,000-square-mile Cariboo, Peter began a career with the Provincial Corrections Branch that spanned nearly a quarter of a century. These writings provide an account of the early days of community corrections in the province and the challenges faced by probation officers like Peter, who were introducing new correctional practices to British Columbia.

***

In my cabin as the Canadian Pacific steamship ploughed its way sedately across the Atlantic in April 1959, I re-read the three letters that Ernie Stevens, the Director of Corrections for British Columbia, had enclosed with his offer of employment after the formality of a personal interview.

In my cabin as the Canadian Pacific steamship ploughed its way sedately across the Atlantic in April 1959, I re-read the three letters that Ernie Stevens, the Director of Corrections for British Columbia, had enclosed with his offer of employment after the formality of a personal interview.

I had been somewhat taken aback to see the word 'Corrections' in the letterhead on Mr. Stevens' letter, for to me it had a 19th-century ring about it. It made me think of the 'cat-o'-nine-tails,’ the squalid British debtor prisons and the sailing ships that deported criminals to Botany Bay penal colony in Australia! Surely not, I thought. But when I re-read those letters from three former British probation officers – Jack Selkirk, Ena Goodacre and Bill Haines – who had spoken so glowingly of their apparently seamless transition from 'assisting, advising and befriending' to' correcting,’ and thought again of Jack driving to work "as the sun rises over the mountains".

***

My initial interview with the Director of Corrections went well. I found Ernie Stevens easy to get along with, especially on learning that he had been a newspaperman like me. Doug Davidson, the Assistant Chief Probation Officer, told me that I would spend several weeks at headquarters 'getting the feel of things' before being posted to anywhere in British Columbia! When they told me that England could fit nicely into Vancouver Island, I couldn't believe it until I looked at a map.

I imagine that it was on my first day that I was introduced to the Deputy Director, Selwyn Rocksborough-Smith. Yes, this affable, broad-shouldered man was indeed the brother of the spare, reserved man who had inspected my work in Bristol four years earlier! He had risen from housemaster to an Assistant Borstal Governor in England before being recruited in 1947 by the Attorney General of B.C. to re-open the New Haven institution after the war as an open Borstal, or youth custody centre. In 1958, he had been appointed Deputy Director.

As it turned out, I spent six weeks at headquarters. I did get some court time in, of course, mostly observing, but I know I did at least one pre-sentence report, on an 18-year-old youth who was charged with simple possession of marijuana. The drug problem had not hit Britain yet, and I knew next to nothing about marijuana. In my naïveté, and since the lad had never been in trouble before, I had suggested probation – not knowing the going sentence for simple possession was, for a first offence, four months (and for a second, six) in the Young Offenders' Unit at Oakalla Prison. I was, therefore, aghast when the learned magistrate testily threw down my report and handed down the usual sentence.

***

British Columbia's probation service, after some faltering pre-war experiments in Vancouver with volunteers, had sputtered out with the outbreak of war and officially come into being in 1942. (There had been Juvenile Courts in Vancouver and Victoria since 1910.) Ernie Stevens, who had been, largely it seems, on his own initiative a "follow-up” or parole officer for adult offenders in Vancouver, was in 1943 appointed Provincial Social Service Officer. This title was amended in 1946 to Provincial Probation Officer with the passing of the Probation Act of British Columbia, and in 1951, he was also made administrative head of provincial gaols. It was, therefore, still a very young service when I arrived in 1959.

***

The next day, when Doug Davidson handed me the keys to a huge Ford Meteor, I couldn't help noticing that he had his fingers crossed. He told me to keep driving for 400 miles, by which time I “should hit Williams Lake.”I was to open up a brand new office, for I would be the Cariboo's first probation officer. In addition to serving the magistrate at Williams Lake, the economic hub of this logging and ranching country, I would also be available to the magistrates at 100 Mile House, Clinton and Lillooet. I looked at my map and saw to my dismay that my territory was roughly 120 miles long and 100 miles wide. Twelve thousand square miles! Ye gods! I turned on the ignition and headed in the direction Doug Davidson had indicated. This was going to be rather different from the square mile I had left in Bristol two months before.

The next day, when Doug Davidson handed me the keys to a huge Ford Meteor, I couldn't help noticing that he had his fingers crossed. He told me to keep driving for 400 miles, by which time I “should hit Williams Lake.”I was to open up a brand new office, for I would be the Cariboo's first probation officer. In addition to serving the magistrate at Williams Lake, the economic hub of this logging and ranching country, I would also be available to the magistrates at 100 Mile House, Clinton and Lillooet. I looked at my map and saw to my dismay that my territory was roughly 120 miles long and 100 miles wide. Twelve thousand square miles! Ye gods! I turned on the ignition and headed in the direction Doug Davidson had indicated. This was going to be rather different from the square mile I had left in Bristol two months before.

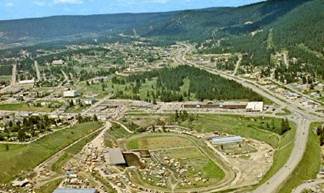

It was the end of May, and spring was turning into summer. The pastoral Fraser Valley gave way to the awesome Fraser Canyon and, by early afternoon, I was driving through the rolling hills and lakes of the Cariboo.....Clinton.... Lac La Hache..... 100 Mile House... then Williams Lake at last came into view; at least, that's what the highway sign said. A huge truck carrying a load of logs approached, swaying ominously. So this dusty, sprawling community would be my home for the foreseeable future! Doug Davidson, taking a chance I would arrive in one piece, had booked a motel cabin for me, and I found it easily enough, a second floor unit overlooking the lake.

It was the end of May, and spring was turning into summer. The pastoral Fraser Valley gave way to the awesome Fraser Canyon and, by early afternoon, I was driving through the rolling hills and lakes of the Cariboo.....Clinton.... Lac La Hache..... 100 Mile House... then Williams Lake at last came into view; at least, that's what the highway sign said. A huge truck carrying a load of logs approached, swaying ominously. So this dusty, sprawling community would be my home for the foreseeable future! Doug Davidson, taking a chance I would arrive in one piece, had booked a motel cabin for me, and I found it easily enough, a second floor unit overlooking the lake.

I was hot, tired and hungry. And I suddenly felt very alone and unsure of myself. I looked down at the stream of cars taking working folk home to their families, and realized I knew not a soul. I looked at my unopened suitcases and, for the first time since leaving England, wondered if I'd made the right career move after all. Then there was the sound of pounding footsteps on the stairs and a knock on the door.

"Hi! I'm Tom Beames, the high school principal. Come and have supper with the family.”

***

100 Mile House was a much smaller town of just one main street, I learned from the polite but rather distant corporal at the RCMP detachment, served many outlying communities, and here the magistrate was a retired police officer from the former B.C. Provincial Police. He seemed to be a stolid but reasonable man who, however, didn't think he would have much to send my way. I gave him one of the cards Doug Davidson had had printed up for me and went on to Clinton. The corporal there was, by contrast, very friendly and even offered to take me on a tour of his area in a police car. I was faced with a quick judgment call and may have made a diplomatic error when I declined with thanks, thinking that I might thereby be too closely associated with the police. However, I don't think too much harm was done. Here, the magistrate was a local sawmill operator, and he never allowed court to interfere with his work! So I had to get used to getting a call from Clinton RCMP just as I was settling down to my evening meal after a busy day around Williams Lake: "Can you get down here for court, Pete? We’ve got a case that might come your way.”

***

I now realized that, outside Vancouver and perhaps Victoria, justice in B.C. was dispensed by lay magistrates, who sat alone and in most cases were advised on the law by a police officer. In contrast, in Britain, three magistrates – one a woman – were required at every sitting; they had to form a consensus before adjudicating, and were advised on matters of law by a legally trained clerk.

***

I will always remember my first probationer. Knowing I was coming, the Williams Lake magistrate had placed a juvenile on six months' probation before I arrived. I can't remember his name or what he had done to earn this dubious distinction, but I certainly remember where he lived – Dog Creek. Apparently, instead of taking the school bus back home, he had got up to some kind of mischief in town. After some searching, I found Dog Creek on my road map, way off the highway on a wiggly thin line that led to the heart of the ranching country. I asked Sgt. Johnson what the road was like. "Well, it's a dirt road, and you don't want to get stuck in the shoulder ruts left by logging trucks, so keep to the centre of the road. But there you've got to watch for rocks hidden under grass tufts. They'll take your oil pan clean out. And listen out for those logging trucks on corners. They’ll blow their horn, but they won't slow down for you. But it's a good road!" I admit I enjoyed that journey, or rather, that adventure. I had certainly experienced nothing like it in Bristol! Dog Creek turned out to be a little green oasis in a dusty, brown landscape. I introduced myself to the youth and his parents, who, I seem to remember, owned a small ranch. It was soon clear to me that this was a decent, law-abiding family and that my first probationer, a likeable lad who had never been in trouble before, was not going to need much, if any, supervision. I planned to drop by once a month for three months and then ask the magistrate to terminate the order. As I drove back to Williams Lake, the late afternoon sun slanting across the hills made the scene worthy of a picture postcard.

My first adult probationer came to me in the aftermath of the Stampede. Or, perhaps I should say, I went to him. I learned that this young man had come into town with friends by truck from Bella Coola and, possibly just because it was the thing to do, got himself put in the drunk tank overnight. My training in England told me that a home visit was warranted, never mind that Bella Coola lay on the coast three hundred miles westward across the Chilcotin. How could I do my job properly without doing a home visit? When the Social Worker responsible for the Chilcotin heard I was going to Bella Coola, he instantly suggested that perhaps he could come along, and after dispensing a few social assistance cheques, he might get in a bit of fishing. That was fine by me, and off we went one Friday afternoon in my government car.

***

The 600-mile round trip went off well: the young man was apparently no problem on his home turf, and my only mishap was a flat tire on the steep, winding hill that descends into Bella Coola. Back in Williams Lake, I duly sent off my monthly expenses sheet to head office. It never crossed my mind that there might be a problem – so I was quite taken aback when I got a phone call from Doug Davidson.

“What the devil were you doing in Bella Coola?” he demanded.

"Doing a home visit," I replied, mystified. “I can’t expect a probationer to drive 600 miles to report, so I plan to visit him once a month.”

"You'll do nothing of the sort,” snorted the Assistant Chief Probation Officer. “You’ll delegate supervision to the R.C.M.P."

“O.K, O.K.” When in Rome....

I got through to a very obliging corporal at the Bella Coola detachment, whom I phoned once a month for six months and who reported that all was quiet on the Western Front.

My caseload grew slowly throughout that summer, most of it emanating from the Williams Lake magistrate. Some of my 'local' probationers lived in the outlying communities of Alexis Creek and Riske Creek to the west of Williams Lake, in Likely and Horsefly to the east, in 150 Mile House to the south, and up the highway between Williams Lake and Quesnel. This entailed a lot of driving on graded dirt roads, frequently trapping me in choking, gritty dust between two logging trucks driven, it seemed to me at times, by recently released patients from Riverview Mental Hospital.

It was out of the question to expect even these 'local' probationers, especially juveniles, to travel miles to report to me. Gradually, I worked out a schedule that saw me on the road many miles each day, calling in on homes and hoping that the family had remembered I had arranged to drop by. It was very much a hit or miss arrangement and I found it very unsatisfactory, but I saw no other way to cover this vast area.

***

It was when I realized that so few people seemed to understand my role that I started to write the occasional letter to the editor of the Williams Lake Tribune. On learning that a juvenile had been placed in a police cell together with adults, because there was no separate cell for juveniles, I wrote condemning the practice, and went on:

"Children of tender years, some emotionally disturbed, are incarcerated in small, dark police cells for days on end (a medieval practice if ever there was one), or in the company of adult criminals, some of whom have long criminal records. This is how many young offenders are expected to begin their rehabilitation, by being tutored in the art by the 'old hands.'"

And when the Williams Lake magistrate sent a local youth, described as "brilliant" but ruled to be "incorrigible," to the Brannan Lake Industrial School for Boys, I wrote another letter, as follows: "My Webster's dictionary defines 'incorrigible' as 'bad beyond correction, irreclaimable' and I think most people would agree that the word itself suggests a despairing finality, a state of permanence. Why not 'beyond control,' a phrase which indicates more accurately the temporary nature of the affliction, and holds out some hope of reformation?"

Whether either letter made more than a ripple in this busy community, where timber and cattle prices were uppermost in the minds of many of its citizens, is doubtful. But emboldened, I contacted the local Kiwanis Club and offered to give a talk on my work at their next meeting. Perhaps a little bored with timber and cattle prices – or were they just being polite? – they accepted my offer. The nub of my talk was what I felt was a growing need for a Cariboo remand centre. In justification, according to the report in the Tribune, I recounted how: "Only last week, two teenaged girls who had absconded from the Girls' Industrial School spent several days in police cells here. At least one had absconded on a previous occasion and was known to be a very tough nut. They were then joined in a small cell by a third girl, the day after her 17th birthday. This girl, far from being tough, is weak and easily led. One can easily imagine that by the time the two left to go back to the Industrial School, the new arrival had been taught every trick in the book."

The newspaper report ended by saying I hoped before long to call a meeting of people interested in such a project. Perhaps the response I got – none – persuaded me that such a meeting was premature.

***

In 1960, I took over the Richmond office. That's not quite correct, because there was no Richmond office, and would not be for a year or so. With the help of the magistrate, I was given an unused room, a table and two chairs in the Municipal Hall for reporting sessions. But no phone! As I lived in Vancouver, I would call in at headquarters every morning for phone messages and to dictate letters, and every evening would mentally "pull up" Oak Street bridge behind me to separate work from leisure.

But I also served the Delta magistrate, a retired police officer, and on my one day a week in Delta, I would hold a reporting session after court in the magistrate's tiny office behind the tiny courtroom adjoining the tiny police office in the tiny basement of the tiny Municipal Hall! This became the village museum when the new Municipal Hall and Justice facility were built. Then I would race – never exceeding the speed limit, of course – up River Road to see my probationers in a tiny cubicle in the Scott Road Fire Hall. You can imagine the excitement when the fire alarm bell rang, as it sometimes did in the middle of an interview, to the delight of all, including myself.

But I also served the Delta magistrate, a retired police officer, and on my one day a week in Delta, I would hold a reporting session after court in the magistrate's tiny office behind the tiny courtroom adjoining the tiny police office in the tiny basement of the tiny Municipal Hall! This became the village museum when the new Municipal Hall and Justice facility were built. Then I would race – never exceeding the speed limit, of course – up River Road to see my probationers in a tiny cubicle in the Scott Road Fire Hall. You can imagine the excitement when the fire alarm bell rang, as it sometimes did in the middle of an interview, to the delight of all, including myself.

***

I had inherited an active, full caseload from my predecessor and soon got stuck into it. As the sole probation officer for the first three years, I must have supervised both sexes – although I can't recall supervising any females – until I was joined by Marge Dennett in 1963, by which time we had an office. But in contrast to the relatively unsophisticated clientele I had had in the Cariboo, I found myself dealing again with a sizeable number of the same sort of streetwise youths and their ambivalent parents I had worked with in Bristol. I can still see myself standing on the doorstep as one indignant father, his erring son at his side, assured me that all boys did 'B and E’s’ and what was the big deal, anyway? But whereas my Bristol probationers called the police 'the law', these called them 'the pigs.’ So why should they take any notice of this new guy who talked funny, knew nothing about hockey or baseball, didn't know who Buddy Holly was, and had never even tried marijuana?

***

The monthly in-house Probation Branch Bulletin, a lively compilation of contributions from all over the province, was being ably edited by Bill Jackson at headquarters, and in the July 1961 issue I took a colleague to task for asserting in the previous issue that much was being done for juvenile offenders to the neglect of adult offenders. I pointed out that on the contrary, in many areas of the province, there was no probation service; juveniles were being 'thrown' straight into the Industrial Schools, after which there was no after-care, and first offenders were routinely remanded in the local lock-up, except in a few major cities.

"Isn't it time we stopped rushing our 'fire engines and ambulances' to the bottom of the cliff," asked, "and instead set about repairing the holes in the rather frail fence at the top? Perhaps if this fence was stronger and more extensive, there would be less need for the huge expenditure on rescue work when it was so often too late.”

Out of that initial gambit was born the Corrections Courier, a quarterly I edited throughout the 1960s, which was funded by the B.C. Corrections Association. I find it hard to believe now, but it was produced on a duplicating machine by Herb Pinchin and myself at the Vancouver Juvenile Court after work, and then, on a Saturday morning, assembled and stuffed into stamped, addressed envelopes at Herb's home by Herb, his wife and son, my sister, my nephew and myself. Talk about a cottage industry!

From about 1965 onwards, we also produced an annual Courier Anthology thought to contain the best of the previous year's articles. It was printed by the print shop at Saskatchewan Penitentiary, through, I think, the good offices of John Braithwaite of the Canadian Corrections Association. And believe it or not, both reached a circulation of about 300 copies, being mailed to addresses throughout North America and even in India, Holland and the U.K.!

***

Many changes in the justice system were happening in the early years of the decade. In 1962, Ernie Stevens retired and Selwyn Rocksborough-Smith – sorry, 'Rocky' – succeeded him as Director of Corrections. He appointed as his Deputy Dr. Malcolm Matheson.

Many changes in the justice system were happening in the early years of the decade. In 1962, Ernie Stevens retired and Selwyn Rocksborough-Smith – sorry, 'Rocky' – succeeded him as Director of Corrections. He appointed as his Deputy Dr. Malcolm Matheson.

In 1963, the Province formalized Family and Children's Courts with a number of measures, which included a requirement that every municipality have a Family Court Committee that 'shall examine the resources of the community for family and children's work... and generally make such recommendations to the Court, the Chief Probation Officer, or the Director of Welfare for the Province as may seem proper.' Another measure: the Attorney General 'may declare any place, house, home, or institution a detention home.' Now we were getting somewhere! It wasn't long before the Richmond Family Court Committee was formed. But more importantly – from my very practical point of view at any rate – every municipality had to make provision for a probation office! I think that was when I at last got an office in Richmond. With a phone, yet!

***

By the end of 1970, a reasonable array of resources was available to the juvenile court. In addition to the S.A.L.T weekend program at Porteau Cove, and the Probation Hostel at Marpole housing eight boys, there was the House of Concord run by the Salvation Army in Langley with beds for 18 boys and plans to increase that number to 65, and the newly-opened Maples in Burnaby for emotionally disturbed juveniles of both sexes. Locally, Father Patrick, an enterprising Catholic priest, was running a group home for boys, and of course, there was Richmond Receiving and Remand Home, housing eight. A few hardened juveniles were still sent to the maximum security Vancouver Detention Home, now at a cost to the municipality of $16 a day. But there were waiting lists everywhere.

***

When I advised my Local Director in 1982 that I planned to take early retirement a year hence, it was agreed that I wouldn't take on any new cases, but would devote most of my time to dealing with cases recommended by Crown counsel for diversion. This concession made my final year a relatively pleasant winding down of my career. I knew I needed to slow up somewhat. In my zeal, I was prone to forgetting that a judge was not bound to accept my recommendations, appropriate as I thought they were. At least two judges had told me privately with some asperity that they did not appreciate being glared at in court! That surprised me, as I had worked hard to achieve what I thought was a stare that was still respectful but conveyed disagreement. I didn't recognize it at the time, but I was clearly what is now called pushing the envelope!