Capital Asset Management Framework: 4. Planning

- 4.1 Introduction

- 4.2 Service Plan

- 4.3 Needs Identification & Analysis

- 4.4 Exploring Options to Meet Service Delivery Needs - Strategic Options Analysis

- 4.5 Business Cases

- 4.6 Program and Project Lists

- 4.7 Performance Measurement & Reporting

- 4.8 Capital Asset Management Plans

4.1 Introduction

Capital asset management planning is the process of identifying current and future capital needs, and developing strategies and projects to address those needs.

B.C. uses a consolidated capital planning process wherein public-sector agencies’ capital plans are consolidated into a single plan to support effective financial and risk management of the government's bottom line.

As part of this process, agencies are encouraged to develop rolling, multi-year capital asset management plans (also referred to as capital plans) that flow from and support their service plans. These plans should reflect the operating and capital cost of managing assets through their life cycles.

This chapter:

- explains key tasks and elements agencies should consider in their capital planning processes, and

- identifies the outputs or products from these processes that should be included in agencies’ capital plans

For a detailed description of the consolidated capital planning process, see Chapter 5.

4.1.1. Key Elements of Capital Planning

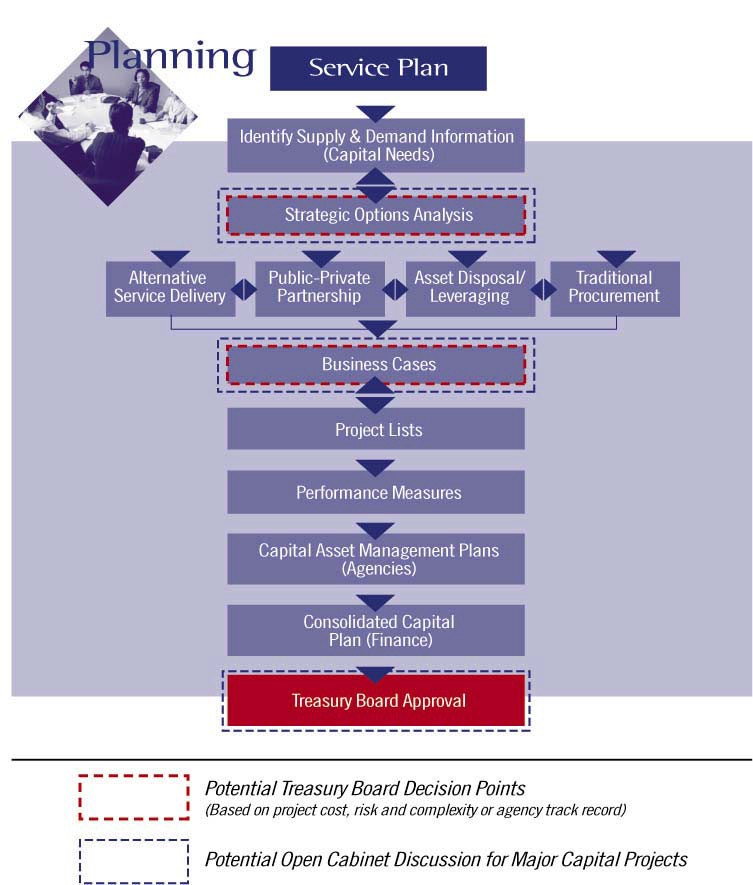

Figure 4.1.1 illustrates the main elements of the capital planning process. It also identifies potential Treasury Board decision points. These depend on the project costs, risks, complexity and/or the agency’s track record to date.

This chapter is organized to generally correspond with the elements identified in Figure 4.1.1. However, this is not intended to suggest that capital planning is a linear process, or that the guidelines in this section should be followed in the order in which they appear.

Recognizing that capital planning happens continuously and often involves simultaneous processes, agencies are encouraged to use the guidelines in the order that best suits their individual needs.

For an overview of the content and organization of capital plans, refer to Section 4.8.

Figure 4.1.1

4.2 Service Plan

The purpose of capital planning, and all capital projects, is ultimately to meet or support service delivery needs. Every public agency in B.C. is responsible for delivering a range of core services, as set out in its service plan, and this should be the central factor driving the capital planning process.

Agencies’ capital plans should clearly articulate the links between their service plans and capital plans, including:

- a description of the mandate, core services and priorities in the service plan

- an explanation of how the capital plan supports the agency’s service plan, and

- where relevant, a summary of how the agency’s plans link to broader government strategic priorities

This information is important for decision makers, ensuring that they view an agency’s capital plan in the proper context. It also supports agencies to stay “on strategy” throughout the capital planning process.

4.3 Needs Identification & Analysis

During this phase of the capital planning process, agencies analyze their service delivery needs by:

- examining factors driving need

- assessing their asset bases, and

- based on these assessments, forecasting capital asset needs, including maintenance requirements and a contingency fund for emergencies

Each of these steps is addressed in detail in the following sections.

4.3.1 Factors Driving Capital Needs

A broad range of factors can affect an agency’s capital needs. Some of the most common are outlined in Figure 4.3.1.

Figure 4.3.1

| Factors | Description |

|---|---|

| Demographics | Agencies should consider both current and future indicators, such as population change by age; impacts of births, deaths, immigration and emigration; and issues specific to program areas. |

| Program changes | Examples include the impact of web-based technologies on distance learning or e- business opportunities. |

| Technological changes | These include current and projected financial or economic/market trends and opportunities – in general, or specific to the service sector. |

| Economic or business changes | These include the impact of any potential changes to environmental standards. |

| Social changes | Agencies should consider any trends that could affect service delivery needs. |

| Legislation | Factors to consider here include any new statutory requirements affecting the agency or its service plan. |

Agencies’ capital needs will be affected by different factors, but all capital plans should include:

- an analysis of the most significant factors driving capital needs, and

- an overview of the methodology underpinning the agency’s demand-forecasting models

4.3.2 Inventory Information

Inventory information is critical to capital planning and should be updated on a rolling basis. Every public agency should develop and update annually a comprehensive asset inventory, including an assessment of the physical condition, functionality (i.e. ability to support current program delivery) and utilization (i.e. capacity) of its capital stock.

This inventory information:

- allows for meaningful comparisons between assets

- helps form the basis for ranking projects

- informs the nature, cost and timing of work required, including renovations and maintenance, and

- supports agencies to develop strategies to meet service needs in the most cost effective and efficient manner (e.g. identifying and capitalizing on excess capacity)

Figure 4.3.2 outlines the types of information generally tracked by an asset inventory.

Figure 4.3.2

| Asset Information | Description |

|---|---|

| Baseline information |

Information on assets such as land, buildings, building systems and equipment, such as:

|

| Physical condition and risk factor | An assessment or rating of the physical condition of the inventory, including maintenance requirements, seismic vulnerability, asbestos, etc. |

| Functionality | An assessment of how effectively each asset meets existing program or service needs; functionality is sometimes measured as the difference between current operating costs and the projected cost of operating a "state of the art" facility. |

| Utilization | An assessment of how each asset is being used; this is sometimes measured by comparing forecast service demand against an asset’s current capacity to determine whether there is an excess or a shortage of capacity. |

A capital plan should include an overview of the agency’s capital stock, including its average age and condition, utilization, suitable valuation(s) (e.g. replacement cost and book value) and a description of any major inventory issues the agency feels are relevant (e.g. deferred maintenance, excess capacity, etc.).

4.3.3 Maintenance, Repair and Rehabilitation

One of the key priorities of provincial capital management is to safeguard the Province’s investment in its capital stock. Deferring maintenance can save money in the short term, but it creates a future liability which will continue to increase over time.

As part of the full life-cycle approach, agencies should adequately plan and budget for maintenance needs to ensure that capital stock meets or exceeds its expected economic life. This planning is based on inventory assessments (as described above) and appropriate methodologies to estimate maintenance needs for an agency’s full portfolio of assets.

Maintenance requirements should be identified in capital plans as a need. Capital plans should also provide details of the methodologies used to develop the forecasts such as the measurement tools, standards and formulas based on asset value or square footage.

4.3.4 Quantifying Needs

Agencies may identify a diverse range of capital assets required to meet the objectives in their service plans. The potential cost of each of these assets should be determined (typically covering three or four years) to allow agencies to:

- assess their ability to meet their objectives, within what is available within the prevailing fiscal framework, and

- assess projects and develop strategies to meet those objectives

Agencies should apply budgeting tools or models to estimate the. A range of budgeting tools is discussed in Chapter 9, Budgeting and Cost Management.

Categorizing or grouping needs can also support effective decision-making at both the agency and central government levels. Capital needs can be grouped by program area, business sector, construction type or accounting treatment. Or, consistent with accounting terminology, they may be grouped to reflect the type of need they represent, such as maintenance/repair, renewal/rehabilitation, and replacement or expansion (new construction). At a minimum, the Province supports a categorizing approach based on generally accepted accounting terminology.

Estimates of capital asset related needs should be aggregated into identifiable categories in capital plans as outlined above. The following issues should also be addressed:

Fiscal situation

Capital plans should include a high-level overview of the agency’s fiscal situation, including a discussion of debt, debt service, amortization and other future-year operating costs

Pre-planning and pre- feasibility requirements

Capital plans should include a forecast of budget needs for pre-planning or pre- feasibility studies and a description of the methodology used to prepare the forecast.

Contingency for emergency requirements

As part of the full life-cycle approach, agencies need to plan and budget for unforeseen emergencies that have the potential to undermine ongoing services, programs or business. These may include:

- immediate health or safety issues such as fire loss, access barriers, mechanical failure or roofing failure, or

- immediate program space demands due to such things as property loss, changing program parameters or changes in an agency’s legislative obligations

Agencies should establish procedures to manage emergency budget risks, ensuring appropriate insurance coverage and/or working with the Risk Management Branch, Ministry of Finance, as needed. These procedures should be identified in capital plans as a budget contingency item. Capital plans should also describe the methodology used to estimate contingency requirements and/or the process used to address emergency issues.

Planning models and assumptions

Capital plans should outline the planning models used to estimate needs. They should also detail the critical material assumptions made in planning and the sources involved (e.g. discount rates, amortization periods, asset valuation methodologies and market assumptions).

4.4. Strategic Options Analysis - Exploring Options to Meet Service Delivery Needs

One of the key objectives of the Capital Asset Management Framework is to support ministries, health authorities, school districts, Crown corporations and other public agencies to think creatively and find the most efficient ways to meet the Province’s capital needs associated with meeting service delivery needs. Agencies are encouraged to be innovative and to challenge traditional service delivery approaches and assumptions.

That means looking at a full range of options for meeting service delivery needs. It also means considering key questions, such as:

- Is there a way to meet our needs without new capital spending?

- Is there a way to better use or manage existing assets that could reduce the need for additional expenditures?

- Is there a way to share the cost and risk of capital acquisition with a partner such as the private-sector or another public-sector agency?

Agencies should also consider traditional approaches (i.e. public financing and service delivery). No final decisions should be made until the agency has identified and considered the options that achieves the greatest value for taxpayers.

Greater integration between the private and public sectors has the potential to improve services, increase efficiency and deliver value for money. It may also generate financing options which reduce the requirement for taxpayer-supported debt.

However, there should be no presumption that either sector is inherently more or less efficient. Decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis, supported by analysis of all practical options.

To support these determinations, the following section describes:

- the range of strategies agencies should consider to meet service delivery needs

- key value for money and public interest issues that should be considered when assessing options, and

- the Strategic Options Analysis to assess the strategies and options to identify the best approach

4.4.1 Alternative Service Delivery

In examining options to meet service delivery needs, agencies should consider alternate service delivery methods, potentially changing the way services are delivered to avoid or limit capital spending. Examples include:

- developing new service delivery methods

- outsourcing

- implementing demand-management techniques (e.g. pricing alternatives such as peak load pricing)

- improving asset utilization for example, extending hours, developing more efficient space standards, introducing scheduling strategies or changing approaches to managing service (i.e. catchment) areas

- enhancing technology (e.g. electronic service delivery)

- reconfiguring programs

- forming partnerships with non-government organizations or other levels of government

- jointly using facilities, and/or

- sharing services with other agencies

This is not a complete list of alternative service delivery methods. Agencies are encouraged to identify as many options as may be feasible that could be used to effectively achieve service delivery outcomes.

4.4.2 Alternative Capital Procurement

Alternative capital procurement refers to any method other than the traditional buy-and- borrow approach (e.g. public financing and service delivery). It involves the acquisition of capital assets and services:

- With financing provided by the private-sector

- transferring some or all of a project’s life-cycle risks to outside parties, or

- transferring some or all of a project’s life-cycle risks to outside parties, and/or

- financed with limited or no recourse to the Province

This emerging area of capital asset management offers a range of potential benefits, including the opportunity for public-sector agencies to make use of private-sector ideas and innovations. However, the main advantage of alternative procurement remains the potential for risk transfer. Alternative procurement offers the potential for an optimal distribution of risk, whereby risks are assumed by those parties best able to manage them at the least cost while protecting the public interest.

If the private sector is required to provide an asset or a service, agencies using alternative procurement may be able to transfer to the private partner some or all the risks in areas such as design, construction, financing, market, operations, industrial relations and asset ownership (e.g. maintenance or technological obsolescence).

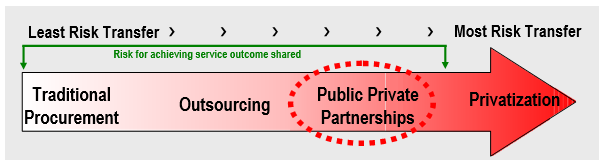

As illustrated below in Figure 4.4.2, one form of alternative capital procurement (known as public-private partnership or P3) is at the higher end of the spectrum of risk transfer from the public to the private sector. By contrast, in traditional procurement, most or all of the risk is retained by the public sector while, in pure privatization, most or all of the risk rests with the private sector.

Figure 4.4.2

With alternative capital procurement, risks should always be allocated to those parties best able to manage them at the least cost while serving the public interest. For example, a private partner may assume the risks related to the potential for unsatisfactory service levels. However, the Province retains ultimate authority and responsibility for providing public services.

4.4.2.1 Forms of Alternative Capital Procurement

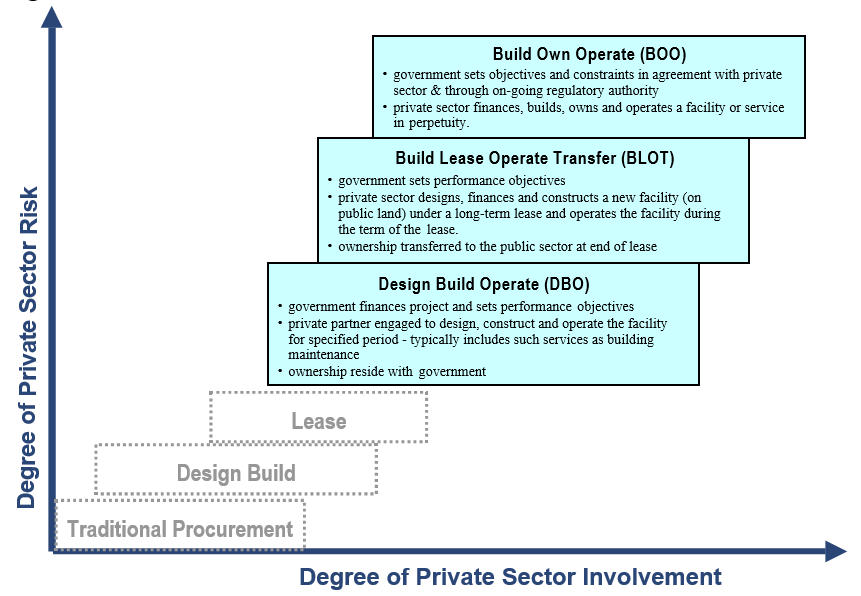

Alternative capital procurement encompasses a wide range of models with a range of implications for issues such as risk transfer, ownership, operations, accounting and debt reporting. In general, agencies should consider whether the public or private sector is better equipped to design, build, finance, operate and ultimately own a given capital asset.

Methods of alternative procurement can include:

- operating leases

- self-supporting projects (e.g. ancillary services at post- secondary institutions)

- internal payback (e.g. energy efficiency) projects, and

- partnership approaches such as joint ventures and public-private partnerships (a variety of models)

Each model has different service delivery potential and, as illustrated in Figure 4.4.2.1, each model is predicated on different levels of risk being transferred or allocated to the private sector.

Figure 4.4.2.1 identifies a sample of alternative models. Agencies should consider as many options as possible to determine which is best able to meet service delivery needs.

Figure 4.4.2.1 - Continuum - Traditional and P3 Procurement Models

4.4.2.2 Identifying Appropriate Projects for Alternative Procurement

Alternative procurement does have advantages, but it is not appropriate in every situation. It may be a feasible option when:

- significant opportunities exist for private sector innovation in design, construction, service delivery and/or asset use

- clearly definable and measurable output specifications

- (i.e. service objectives) can be established, suitable for payment on a services-delivered basis

- a market for bidders can be identified or can be reasonably expected to develop

- there is potential to transfer risk to the private sector

- the private-sector partner has an opportunity to generate non-government streams of revenue (e.g. charge for private access in off-hours), and/or

- projects of a similar nature have been successfully procured using a similar method

Agencies should develop screening criteria to help identify viable alternative procurement projects. Figure 4.4.2.2 identifies six basic types of criteria that agencies can consider.

All screening criteria should be modified as needed to suit agencies' business or program areas, and tailored to the context of specific projects. In general, projects that appropriately address the issues discussed in the table below may be candidates for public-private partnerships.

Figure 4.4.2.2

| Criteria | Considerations | Sample Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Financial | Can the alternative procurement method accommodate financial terms acceptable to both parties? |

|

| Technical | Could alternative procurement result in a technical solution to meet service delivery needs? |

|

| Operational | Could operational hurdles undermine an alternative approach? |

|

| Public Policy | Will the public sector accept private involvement? |

|

| Implementation | Could implementation barriers prevent the use of alternative methods? |

|

| Timing & Schedule | Could time constraints pre-empt alternative procurement? |

|

In addition to using screening criteria, agencies considering alternative procurement should consult with the Provincial Treasury, Ministry of Finance, regarding the appointment of external financial advisors to aid in assessing project economics, appropriate discount rates, financing structures, etc.

4.4.2.3 Accounting Treatment for Alternative Procurement Projects

For budgeting, accounting and financial statement reporting, agencies should follow Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) – regardless of which procurement approach they use. Alternative approaches should be pursued on the basis of the substance of the underlying business case, not as a means of achieving certain accounting or reporting outcomes.

Elaborate structures designed for accounting purposes generally do not withstand the test of time and can result in significant restatement of financial statements in the future. For example, proposed leases have been structured to avoid meeting capital-lease financial tests. Upon analysis, it is clear that these agreements assign little risk to the private sector lessor and may result in the Province taking on most of the risks associated with ownership – without the corresponding benefits. In these cases, thebagency could be required to restate its financial statements.

Levels of risk transfer through alternative procurement should be clearly and accurately identified in the classification of capital financial transactions.

For further information, see Chapters 12 Financing and 13 Accounting. For advice, agencies should first consult with their own financial and accounting professionals and those of their sponsoring ministry. Agencies may then wish to contact the Provincial Treasury and/or the Office of the Comptroller General, Ministry of Finance.

4.4.2.4 Alternative Procurement Tools

Alternative procurement tools are being developed, including examples of alternative procurement models - and their potential risks and benefits - and sample screening criteria.

4.4.2.5 Asset Leveraging

Asset leveraging is the process of maximizing the value of government assets to offset service or capital costs. Examples could include:

- selling or leasing part of a property (e.g. sale and leaseback transactions)

- using excess capacity (e.g. unused space or off-hours use) to generate revenue; and/or

- using other government properties, even those unrelated to the project, to generate revenue for a capital project. Agencies considering this form of leveraging must first assess whether any restrictions exist on their ability to dispose of assets or to use the proceeds of disposal

Asset leveraging may be appropriate when an agency has excess capacity; when program changes render assets obsolete; or when changes in service demand reduce an agency’s capital needs.

4.4.2.6 Traditional (i.e. publicly-financed) Procurement

Traditional procurement is the process whereby public agencies procure capital assets – retaining direct responsibility for financing, design, construction and (usually) operations, and assuming most or all the risks throughout an asset’s life cycle.

This method of procuring is appropriate where it provides the best value for money of the options considered and it is necessary to protect the public interest. Agencies may also wish to assess a traditional procurement approach as a benchmark against which to measure the relative merits of alternative procurement options.

Traditional procurement takes a variety of forms, such as design- bid-build, construction management, unit price, cost plus or design- build.

4.4.2.7 Integrated Strategies

In some cases, the best approach to meeting service delivery needs may be a combination of varying procurement and service-delivery methods, integrated into a single project- specific strategy. For example, one or more aspects of demand could be met through an alternative service delivery strategy such as outsourcing; part of an existing asset could be sold to offset costs. Another aspect of service delivery could be provided through a public-private partnership and, where it provides the best value for money and is necessary to protect the public interest, a portion of service delivery need could be met through traditional (publicly-financed) means.

Finding the best solution will involve considering and analyzing a full range of options, and assessing them against public-interest and value-for-money criteria.

4.4.3 Assessing Potential Strategies

Capital decisions should be based, on meeting service delivery needs. To assess which strategy can do this most effectively, agencies need to determine:

- which service delivery option offers the best value for money, and

- which option best protects the public interest

The following sections describe these concepts in detail, identifying issues that should be assessed during project planning and implementation. It also offers guidance on how the concepts of value for money and protecting the public interest should be applied at critical phases of the project.

4.4.3.1 Assessing Value For Money

In the broadest sense, the option providing the best value for money is the one that uses the fewest resources to achieve the desired service outcomes. Relative value is determined through a rigorous examination of service delivery options and business case analysis, considering a broad range of factors including: service levels, cost, promotion of growth and employment, environmental considerations and other health, safety and economic issues.

A value for money assessment must consider both quantitative and qualitative factors.

Quantitative factors include those to which a dollar value can be assigned, such as initial capital costs, operating and maintenance costs over the life of a project (adjusted for risks), and ongoing operating costs related to service delivery.

Quantitative factors also include those which can be quantified but are difficult to accurately translate into monetary terms. Examples may include the number of indirect jobs created by a project, the potential for broader economic stimulus, the level of measurable environmental benefits or the number of people served within a given timeframe.

Qualitative factors include those to which a dollar value cannot be assigned and may include the nature (e.g. flexibility) and duration of a potential business relationship, the potential for innovation in service delivery, environmental considerations, community impacts, labour relations issues, or the potential for alternative use of an asset.

Qualitative factors should be assessed using an objective and disciplined approach, such as a multiple criteria or accounts methodology.

4.4.3.2 Achieving Value for Money in Alternative Capital Procurement Projects

A number of key factors often contribute to achieving value for money in alternative procurement projects. These include:

- Risk Transfer – Allocating or transferring project risks to the party or parties best able to manage them can reduce the all-in cost of the service to government.

- Innovation – In a competitive market, focusing on outputs rather than inputs gives private sector operators the opportunity and incentive to be innovative in service delivery. The benefits of innovation can be passed on to government.

- Asset Utilization –The private sector is often better positioned to generate proceeds from any surplus facility capacity which can be used, in part, to reduce the cost of services to government.

- Whole Life Costs – In some cases, the private sector is able to provide facilities more cost effectively than government from a whole-life cost perspective (i.e. the costs of design, construction, maintenance, refurbishment and service delivery).

4.4.3.3 Public Interest Considerations

Regardless of who delivers public services, the government has a duty to protect the public interest and users of public services. In determining the best way to meet service delivery needs, agencies must identify the key public interest issues specific to their business and program areas, and determine how effectively each option under consideration can address those issues. Table 4.4.2.2[AS1] identifies a minimum range of public interest issues against which agencies should rigorously assess all service delivery options.

Table 4.4.3.3

| Public Interest | Discussion/Questions to Consider |

|---|---|

| Service Effectiveness | Can required service levels be defined and measured, and can service outcomes be regularly assessed? |

| Accountability and Transparency. | Can the performance of the private provider/operator be monitored and reported, and can adequate accountability measures be put in place? |

| Public Access | Do strategies ensure appropriate access by the public (e.g. access in timely manner and at sufficient locations)? |

| Equity | Do strategies adequately ensure that disadvantaged groups (e.g. people with disabilities) have access to the services? |

| Privacy | Can the strategies be structured to provide adequate protection of individual privacy (e.g. personal information) and where applicable the rights of commercial enterprises (e.g. proprietary rights)? |

| Health and Safety | Does the strategy adequately protect the public and ensure appropriate health and safety standards are met? |

| Consumer Rights | Are the consumer rights of service users adequately protected (e.g. against price increases)? |

| Environment | Is the environment adequately protected? |

| Individual and Community Input | Where appropriate, have potentially affected individuals and communities been consulted? |

4.4.3.4 When and How to Assess Value for Money and the Public Interest

A full assessment of value-for-money and public-interest issues should be continually applied and refined as a project strategy is developed and proceeds through to implementation. Table 4.4.2.3 provides an overview of when and how these issues should be considered at critical points in the planning and implementation processes. It also outlines when and how it is appropriate to apply a Public Sector Comparator (PSC) methodology, as one aspect of a value-for-money assessment.

Generally, the province supports a multiple criteria evaluation approach to systematically and objectively assess value for money and public interest in the planning stages

(i.e. when preparing a strategic options analysis or business case). Analytical methodologies focused primarily on financial or quantitative analysis, such as benefit- cost or cost effectiveness analysis may be appropriate in certain circumstances requiring limited consideration of qualitative criteria (or criteria difficult to quantify).

Table 4.4.3.4

| Key Project Phase | |||

| Strategic Options Analysis | Business Case | Procurement | |

| Value for Money |

Criteria are initially identified and defined. An initial qualitative - strategic level assessment of relative value for money is conducted (i.e. ordinal ranking or assessment of likelihood as opposed to detailed quantitative analysis). |

Criteria are further refined and assessed on a comprehensive and detailed basis. Assessment methodology employed (e.g. benefit-cost, multi-criteria analysis) should be appropriate to the range of criteria being assessed. |

Procurement documents such as Requests for Expressions of Interest or Requests for Proposals include both quantitative and qualitative criteria. |

| PSC |

A preliminary assessment of the costs and risks of the options is prepared to determine affordability. |

When applicable, a detailed PSC is developed as part of the business case. |

The PSC, if applicable, is further refined and used in the evaluation of proposals. |

| Public Interest |

Issues must be identified, defined and then refined as projects develop. All options undergo a qualitative assessment to determine their relative capacity to protect the public interest. |

Issues are refined and clear, measurable standards for addressing them are defined. Business cases should include a full public interest assessment, including the identification of any mandatory requirements to ensure the public interest is protected. |

Procurement documents detail public interest issues and how they should be taken into account. Bids are evaluated against the public interest issues to determine whether they adequately meet the requirements. |

4.4.4 Strategic Options Analysis Methodology

4.4.4.1 Overview

Strategic options analysis (SOA) is a systematic approach to determining the best way to meet service delivery needs. A rigorous SOA, equal with the size, complexity and risk associated with a particular initiative, should be undertaken to support decision-making. This includes consideration of issues such as service delivery outcomes, value for money, the public interest and social, and labour and legal issues.

Preparing a SOA will ensure a thorough, cost-effective, strategic- level screening is completed on the widest possible range of service delivery options (e.g. alternative service delivery, leveraging and alternative procurement) before an agency invests in detailed and

- costly business case development. A SOA also allows key decisions to be made early in the project’s planning cycle, and helps agencies to:

- identify the critical business and public policy issues that need consideration

- identify and critically examine the financial and other advantages, disadvantages, risks and benefits to government of each available option

- identify and provide a clear rationale for a preferred option or short-list of options for further evaluation

- determine the appropriate depth of business case analysis needed, and

- provide a sound basis for key strategic decisions to meet service objectives, provide value for money and protect the public interest

Like a traditional business case analysis, a SOA should consider the implications of each option over the full life cycle of capital assets. However, a SOA is a higher-level analysis, typically based on preliminary cost and benefit estimates and only a qualitative assessment of risks. It is primarily focused on policy-level decisions and may not address some business case elements such as context assessments, implementation and risk management. Rather, it provides the basis for a targeted business case analysis, focusing on the best option(s) for meeting service delivery needs.

4.4.4.2 Basic Elements of Strategic Options Analysis

Generally, a strategic options analysis should include the five basic elements outlined in Table 4.4.3.2.

Table 4.4.3.2

| 1. Description of the Service Challenge/Problem | This should be a future-oriented outline of the fundamental service challenge or problem the agency wants to address, consistent with its service plan. A service challenge statement should focus on preferred service outcomes rather than outputs or activities. |

| 2. A Full Range of Strategic Deliver Options |

This section should describe a full and innovative spectrum of options including non-asset solutions, alternative service delivery mechanisms, public-private partnerships, traditional procurement approaches and leveraging of capital assets. It may also include an appropriate reference or base-case scenario indicating, for example, the most likely outcome if the recommended solution is not adopted, or if a traditional (publicly financed) alternative is adopted. |

| 3. Preliminary Evaluation of Options |

This involves identifying quantitative and qualitative criteria for screening options and, at minimum, a qualitative assessment of the issues and implications of the various options, relative to each screening criteria. A comprehensive set of financial and non-financial criteria should be developed, including criteria focused on value for money and protecting the public interest. A qualitative description of advantages and disadvantages can also be used in evaluating options depending on the nature of the criteria. Information on comparative results is often summarized in a table format where columns are used to list options, and rows list the criteria used in the evaluation. |

| 4. Preliminary Risk Assessment | This involves a high-level analysis of potential risks to estimate their likelihood and consequences (i.e. the potential level of risk), and establish relative risk priorities. The degree of rigor required in carrying out this risk assessment may vary depending on the nature of the service challenge and the nature of options under consideration. Identification of potential risk mitigation strategies should also be included. |

| 5. A Screened, Ranked Short-List of Options | Typically the short-list consists of the most promising strategic options and a recommendation to senior decision-makers on preferred options for further analysis. The short-list should describe the major features of each option and explain why the prioritized list is the preferred set (often presented in tabular form). |

4.4.4.3 Applicability – When to prepare a Strategic Options Analysis

As with most decisions in the capital planning process, the specific characteristics of a project will determine whether, and to what degree, an agency should prepare a strategic options analysis (SOA). An initial assessment of project complexity, risk and cost should be undertaken before a detailed SOA is completed. For more direction on making this assessment, see Section 3.2.1 which discusses risk rating.

Generally, if a project is likely to be complex or raise difficult policy issues, the agency should complete a SOA. For lower-risk projects, a SOA may not be warranted as a simple business case may be sufficient.

Agencies are expected to exercise professional judgement in determining:

- when to prepare a strategic options analysis

- the appropriate level of rigour and detail for the analysis

- a suitable time in the planning cycle for doing the analysis, and

- the appropriate analytical techniques to apply

4.4.4.4 Approval Requirements

Depending on the public policy, organizational or financial issues raised by the options under consideration, agencies may be required to present the findings of the SOA to Treasury Board or other government committees, as part of the capital approval process. The information may be required as part of a capital plan, or as a stand-alone submission.

Agencies must be able to clearly demonstrate how a preferred option will be accommodated within fiscal targets (e.g. operating budget, capital expenditure limits and debt limits). Specific submission requirements will be based on the project’s risk profile and public policy issues, and the agency's delivery and management track record.

4.5 Business Cases

A business case encompasses detailed assessments (e.g. estimates of the comparative costs and benefits) of a variety of:

- financial factors such as life-cycle costs

- non-financial factors such as environmental, job creation public health or other such socio-economic impacts, and

- associated public interest issues such as access, security and safety

A sound business case allows decision-makers to assess the viability of specific initiatives, including their affordability, desirability, efficiency and cost-effectiveness – based on value for money. It also supports the Province to assess and establish priorities in the context of overall service and capital plans, and to evaluate final asset and service outcomes against intended or projected results.

The following section offers a guide for preparing a sound business case, including:

- an overview of elements to address, and

- guidance on determining the appropriate depth of analysis, based on the complexity, risk and size of an initiative

4.5.1 Capital Programs

Some capital projects or expenditures, especially those that are large, complex or carry significant risk, should be analyzed through individual business cases. At other times, agencies responsible for managing large numbers of similar capital expenditures can simplify their planning processes, and required approvals, by categorizing or grouping individual projects or expenditures into "capital programs."

For example, similar expenditures can be consolidated into groups such as: maintenance and repair programs, vehicle replacement

programs, and seismic upgrade programs.

Agencies often standardize business case assessment and project ranking within capital programs, using simplified evaluation processes based on unit rates, guidelines relating to asset life, or other standard decision parameters. This approach to categorizing tends to work best where:

- reliable forecasts indicate that many proposed projects will have very similar features, and

- each group of expenditures will address a recurring problem where a limited number of options or solutions must be repeatedly assessed

4.5.2 Business Case Elements

Table 4.5.2

| 1. Description of the Service Challenge/Problem |

This is typically based on prior strategic options analysis, further refined to address the following questions:

This section should also address the current situation and work-to-date, explaining how the service was delivered in the past and describing the planning undertaken to date, including its history, current status and any commitments made or negotiations under way |

| 2. Analysis or Development of Preferred Options |

This section details the alternatives considered for addressing the identified problem/challenge - typically based on top-ranked options from a strategic options analysis (e.g. covering non-asset solutions, alternative delivery mechanisms, public/private partnerships) and different phasing for implementation or procurement strategies for the preferred solution. This section should also identify a reference or base-case scenario against which to make a meaningful comparison. A base-case scenario is the most likely approach or sequence of results expected if the proposed preferred option does not proceed. The base-case should be a feasible option, allowing a value- for-money comparison and indicating how the problem will likely evolve over time, if the preferred solution is rejected. Where applicable, this is the scenario to which the value-for-money test will be applied when assessing an alternative procurement scenario (e.g. applying a Public Sector Comparator). |

| 3. Evaluation of the Options |

This section should include a context assessment, describing the most significant features of the overall environment in which the initiative will function (e.g. strategic, market capacity, socio-economic, technical, legal and other factors that may affect the project over time). It should also list the selection criteria, including the quantitative and non-quantitative measures and standards used to compare and evaluate the options. Normally, this includes financial, environmental, social and other value-for-money criteria as well as public interest issues, with justification for any criteria unique to the case. Financial criteria include the net present value of quantifiable benefits and costs (measured against a Public Sector Comparator, where applicable) and financial impacts on key stakeholders. Agencies should consult with Provincial Treasury in determining an appropriate discount rate. A risk evaluation is also required, including the identification, analysis, mitigation/treatment, evaluation, and communication of risks, as well as sensitivity analysis including a description of the techniques, and/or approaches used. The risk evaluation should be consistent with government guidelines provided by the Ministry of Finance (Risk Management Branch). |

| 4. Recommendations |

In this section, the agency should describe its preferred solution, including:

A rationale for the preferred solution should be based on the earlier evaluation of options with explicit reference to implications relative to risks and the selection criteria used. This section should also include a description of authorities sought, including at minimum a summary of recommendations to key senior decision-makers and potential funding agencies, and a list of all authorities and decisions being sought from senior decision-makers. |

| 5. Proposed Implementation Strategy |

This section describes the key features and steps necessary to implement the proposed solution to approved scope, within schedule and on or under budget including:

|

4.5.3 Guidelines

A business case should be prepared for any significant capital project. Agencies are responsible for determining the level of analysis required in terms of the number of business case elements addressed, and the depth of analysis in each based on the project’s size, complexity and risk.

Agencies can use the preliminary risk assessment from their strategic options analysis to assess project risk and complexity and determine the type of business case required. Table 4.5.3 provides additional guidance to assess the level of analysis required for a capital project.

Table 4.5.3

| Project Risk & Complexity | Description |

|---|---|

| Large, complex and moderate to high- risk projects | A detailed business case analysis is needed and typically includes a substantive evaluation and comparison of variants of the preferred strategy with one or two variants of the next-most promising options. Each variant should be a real alternative, capable of practical implementation. All business case elements should be included, with detailed analysis and a thorough risk assessment. The latter is critically important when considering alternative service delivery or public-private partnership options. |

| Medium-sized projects of moderate risk or complexity | A less detailed business case analysis is needed and should focus primarily on the business case elements associated with the areas of highest risk, determined through a thorough risk assessment. |

| Smaller, less complex projects | A simplified business case analysis is typically sufficient for lower-risk projects, including those for which a strategic options analysis may not be appropriate. In these instances, only selected (relevant) business case elements are included, and levels of analysis are commensurate with risk. |

4.5.4 Approval Requirements

Agencies may be required to submit specific business cases to Treasury Board as part of their capital asset management plans or as stand-alone submissions. Specific submission requirements will be set out Treasury Board Budget or Decision Letters, Mandate Letters or Treasury Board Directives . This will be based on the project’s risk profile and the agency's delivery and management track record. For details of the Province’s consolidated capital planning approval process, see Section 5.3.

4.5.5 Business Case Tools

Business case tools are currently being developed and will include a more detailed user manual for preparing a business case, with examples of different types of business cases for projects of differing complexity and risk. A sample public sector comparator methodology is also being developed

4.6 Program and Project Lists

4.6.1 Description

Program and project lists are typically aggregated summaries of business cases, ranking projects or programs in order of priority and identifying multi-year (ideally three to five- year) funding strategies reflecting the full life-cycle cost of all capital assets. These lists should demonstrate how an agency is supporting core service delivery, prioritizing its projects, managing its asset base and implementing its capital strategy within its fiscal limits.

The following section describes the key components of project/program lists and offers guidance on:

- ranking methodology

- summary project/program information that should be included in capital plans, and

- project categorization

4.6.2 Project Ranking Methodology

Project (or program) ranking is a systematic way of setting capital priorities. It is particularly useful to agencies examining a broad range of proposed projects, because it provides a means to assess and prioritize competing demands, based on consistent and measurable criteria.

Agencies are encouraged to develop specific and quantifiable project-ranking criteria and to set priorities based on service objectives. Criteria may reflect:

- service needs e.g. projects may be ranked based on their potential to improve program delivery immediately as measured by volume, quality or other standards, or their potential to change program delivery to improve quality or increase volume at a minimal cost

- legislative, legal or contractual requirements

- protection of people, including the need to comply with building codes, health and safety standards or Workers’ Compensation Board requirements

- protection of existing assets, taking into consideration the cost of renovating existing assets vs. the cost of replacement, with facility audits substantiating the scope of work and budget

- cost savings or cost implications; these may be calculated to show the budget implications of implementing a capital project, or the future implications if the project is not undertaken

- service plan targets and strategic fit

- business case criteria measures (e.g. internal rate of return), and/or

- local conditions (physical, economic or demographic)

Capital plans should include a brief description of the ranking criteria and methodology used in establishing agency priorities.

4.6.3 Summary Project/Program Information

Project/program lists included in capital plans should demonstrate that an agency is managing, and will continue to manage, within in its fiscal limits on a multi-year basis. These lists should include summary information that clearly identifies each project and provides key financial and status information, including the project’s current phase (e.g. planning, design, construction).

Table 4.6.3 provides an overview of the information that should be included for each project.

Table 4.6.3

| Information | Description |

|---|---|

| Project description and justification | Information based on key elements of the strategic options analysis and/or detailed business case. For minor projects, the justification may be supported by other means, such as an engineering report. |

| Rank | Project rank showing the project’s place among the agency’s capital priorities. |

| Full life-cycle cost of the project |

Information including:

|

| Project phase and on-going expenditures | Information indicating the project’s current phase (e.g. pre-feasibility, planning, design, engineering, construction, commissioning, etc.) and identifying expenditures that are ongoing and legally (contractually) committed. |

| Funding source(s) | A description of how the project is being funded (e.g. cost sharing arrangements, debt financing, internal financing, user fees, or other revenue sources). |

| Procurement method | Description of how the project is being procured (e.g. by traditional or alternative approaches). |

Project or program lists should be included in agencies’ capital plans, summarized by category. The summaries should be consistent with those used in communicating capital requirements. They may be grouped according to

purpose (e.g. maintenance, renovation, replacement or expansion) or in categories relevant to an agencies’ program areas. For decision purposes, they should also be grouped by delivery method (e.g. alternative capital procurement or traditional/publicly financed procurement).

Where applicable, budget requirements should be identified for pre-feasibility studies, post implementation reviews and contingencies for loss replacement. This supports the Province’s full life-cycle approach to managing capital assets.

4.7 Performance Measurement & Reporting

As part of the Province’s commitment to accountability, public agencies need to measure their performance at every stage of the capital asset management process, at both the corporate and project/program level.

Corporate-level performance measures may include the agency’s ability to:

- manage within fiscal targets (e.g. capital-related) from year to year

- successfully implement proposed strategies and projects from year to year, and/or

- achieve asset management goals such as targets for average age of capital stock, utilization rates, maintenance-expenditure targets and levels of accumulated deferred maintenance

Program or project-level performance measures may include:

- how effectively assets are supporting service delivery objectives

- project management performance, including whether projects are delivered on scope, schedule and budget and whether risks have been effectively managed, and/or

- physical asset performance (whether the planned quantity and quality of assets are achieved)

Capital asset management plans should summarize agencies’ track records in meeting both corporate and project-specific performance measures in previous years. They should also set out measures against which agencies’ future performance will be assessed.

For a more complete discussion of performance measurement concepts, standards and methodologies, see Chapter 11.

4.8 Capital Asset Management Plans

Capital asset management plans capture the most significant information from an agency’s capital planning process. That process should be ongoing and continuous, and the findings should be used to continually update multi-year, rolling capital plans – based on agencies’ service plans and reflecting the cost of managing capital assets through their full life cycles.

The sample table of contents in Figure 4.8 offers general guidance on the structure and contents of capital asset management plans. It also provides descriptions and/or examples of elements that should be included.

Figure 4.8 Sample Table of Contents

Table of Contents

- Overview of Agency

- description of the agency’s mandate and core services as per its service plan, and their relationship to capital asset management

- links to broader government strategic or capital priorities

- relevant capital related organizational or governance structures (e.g. the relationship between ministries and local agencies)

- capital related legislative requirements

- overview of agency-specific funding mechanisms

- Factors Driving the Need for Capital

- identification and analysis of the significant factors underlying the agency’s demand for capital expenditures (e.g. demographics, technological change, market conditions, program changes) and a brief overview of the methodology used to forecast demand

- overview of the agency’s capital stock (e.g. identifying its average age and condition, utilization issues and any major inventory issues) and the methodology used (e.g. asset valuation methodologies) to track and calculate the inventory information

- maintenance requirements and an outline of the methodologies used in these forecasts (e.g. standards, formulas based on asset value or square footage)

- Overview of Capital Related Fiscal Situation

- overview of the agency’s debt, debt service, amortization and/or other capital related fiscal pressures

- material assumptions used in the planning processes and their sources (e.g. discount rates, amortization periods, market assumptions)

- Capital Expenditure History

- brief summary of the agency’s historical spending patterns and priorities

- Forecast of Capital Asset Related Needs

- summary of forecasted capital expenditure requirements, grouped into meaningful categories, such as:

- preplanning/pre-feasibility, with a description of the methodology used to estimate

- the requirements

- maintenance, renovation, replacement or expansion, with a description of the methodology used to estimate the requirements

- allowances, contingency requirements (or another approach) for managing emergency capital requirements, with a description of the methodology used to estimate or address the requirements

- summary of forecasted capital expenditure requirements, grouped into meaningful categories, such as:

- Strategies and Projects to Meet Needs

- where relevant, approaches to formula funding with an overview of the allocation methodology or criteria

- summary of alternative strategies used to meet capital needs, including a discussion of the implications if capital needs exceed affordability

- detailed project/program lists including a brief description of the ranking criteria and methodology used in establishing priorities; the information should be aggregated in meaningful categories for decision-makers and should include:

- a summary of need for each proposal (a brief statement of justification, appropriately reflecting the project’s size, complexity and risk);

- financial, project phase (life cycle) and other relevant information such as procurement method (e.g. P-3), and

- identification and status of ongoing (i.e. legally committed) projects including identification of any substantive issues (e.g. schedule slippage).

- Capital Related Performance Measures and Targets

- summary of an agency's key capital management performance measures, targets and benchmarks

- reporting on previous years’ performance

- Appendices as needed. Examples include:

- identification or summary of budget and planning methodologies applied

- project ranking methodology

- complete strategic options analyses or business cases as required for approval

- supporting reports or studies

4.8.1 Approval Requirements

Capital asset management plans are generally submitted to Treasury Board on an annual basis as per the consolidated capital planning and approval process outlined in Chapter 5.

3. Risk Management < Previous | Next > 5. Consolidated Capital Plan Process & Approvals