Lesson 3: Where Does Karst Occur?

Illustration by P.A. Griffiths

On this page

- Lesson objectives

- Distribution of soluble rocks

- Karst around the world

- Karst in Canada

- Karst in B.C.

- Where can I see karst in B.C.?

- Test your knowledge

Lesson objectives

This lesson focuses on where karst occurs – around the world, across Canada, and within B.C. At the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Name some of the more famous karst areas around the world

- List some of the important karst areas in Canada

- Name some of the important karst areas in B.C.

- List some areas of B.C. where karst can be viewed

Distribution of soluble rocks

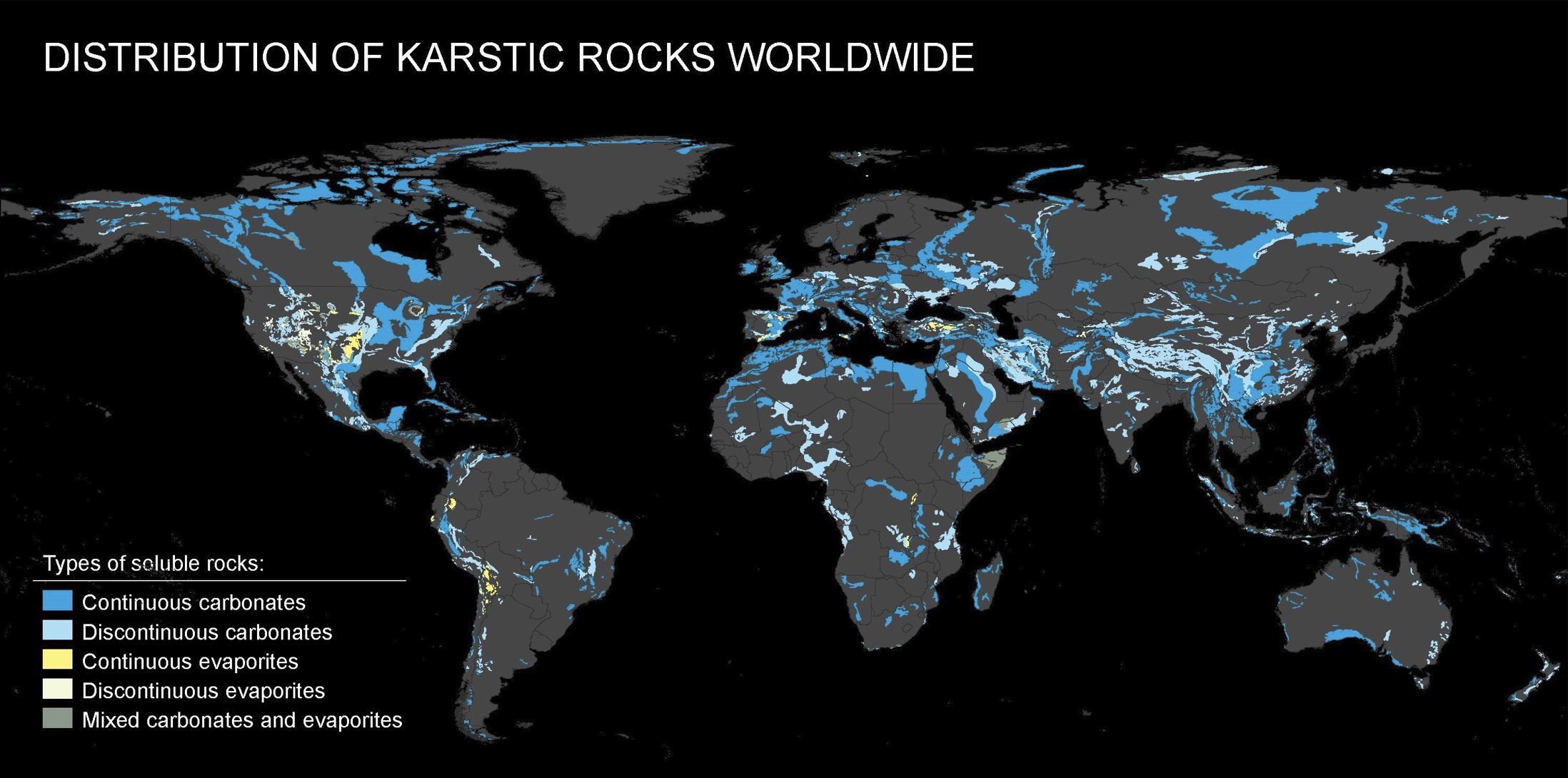

The types of rock in which karst typically forms cover about 20% of the dry, ice-free portions of the earth’s surface. However, karst is not necessarily present in all these areas. As we learned in the previous lesson, in addition to soluble rock, surface karst features and subsurface drainage must also be present. Karst is thought to occupy about 7 to 10% of Earth’s ice-free land surface.

Karst around the world

Karst occurs on every continent except Antarctica.

The original “type site” for karst is the Kras or “Classical Karst.” It is a karst plateau straddling the Slovenian and Italian border on the northeastern end of the Bay of Trieste. The names for this type of site area, “Kras” (Slovene), “Carso” (Italian) and “Karst” (German), are derived from a common root word meaning “rock” or “stony ground.”

Other examples of famous karst areas include the spectacular tower karst of Guilin (China), the Vézère Valley and Ardèche Gorge (France), Aggtelek Karst (Hungary), Dachstein Plateau (Austria), Gunung Mulu Park (Malaysia), Ha Long Bay (Vietnam), the Burren limestone pavements (Ireland), Plitvice Jezera (Croatia), the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site (South Africa), the Tsingy de Bamaraha karst of Madagascar, the Mogote karst of Cuba’s Viñales Valley, the Tongass National Forest (Southeast Alaska), USA (Mammoth Cave National Park and Carlsbad Caverns National Park (USA), and parts of Patagonia (Chile), Belize, and the Yucatan Peninsula (Mexico).

While the basic processes that produce karst are the same around the world, local conditions such as climate, bedrock chemistry, vegetation and soil cover (or lack of it), and overall geological history can produce variation in the types of features present and the degree of karstification. For example, although the basic structure and function of karst in a temperate region that was covered by glaciers in the past may be similar to that of tropical rainforest karst, the two may look very different on the surface. Also, the geological history may be very long and so local conditions that may have produced karst in the past may have changed over time. For example, karst in arid regions today may have been formed at a time in the past when wetter climate conditions were present. The result is that the character of karst in a particular area can be unique and distinctive.

Many UNESCO World Heritage Sites are in karst areas, though the presence of karst is not necessarily the sole reason these sites have been selected for world heritage status.

The short video (linked below), titled “ZIVO: Life and Water in the Karst Region,” provides a brief introduction to the karst in the Istrian Peninsula on the border of Slovenia and Croatia. (A link to a full-length version of this film, which explains the sensitivity and vulnerability of karst hydrological systems in greater detail, is provided in Lesson 5).

Click here to view Zivo Life and Water in the Karst Region Video

Did you know? The letter “k” in “karst” should not be capitalized in most cases. The exception is when “Karst” is being used as a proper noun (that is, in a well-known and or gazetted name or title for a specific area) like the Classical Karst (or Kras).

Karst in Canada

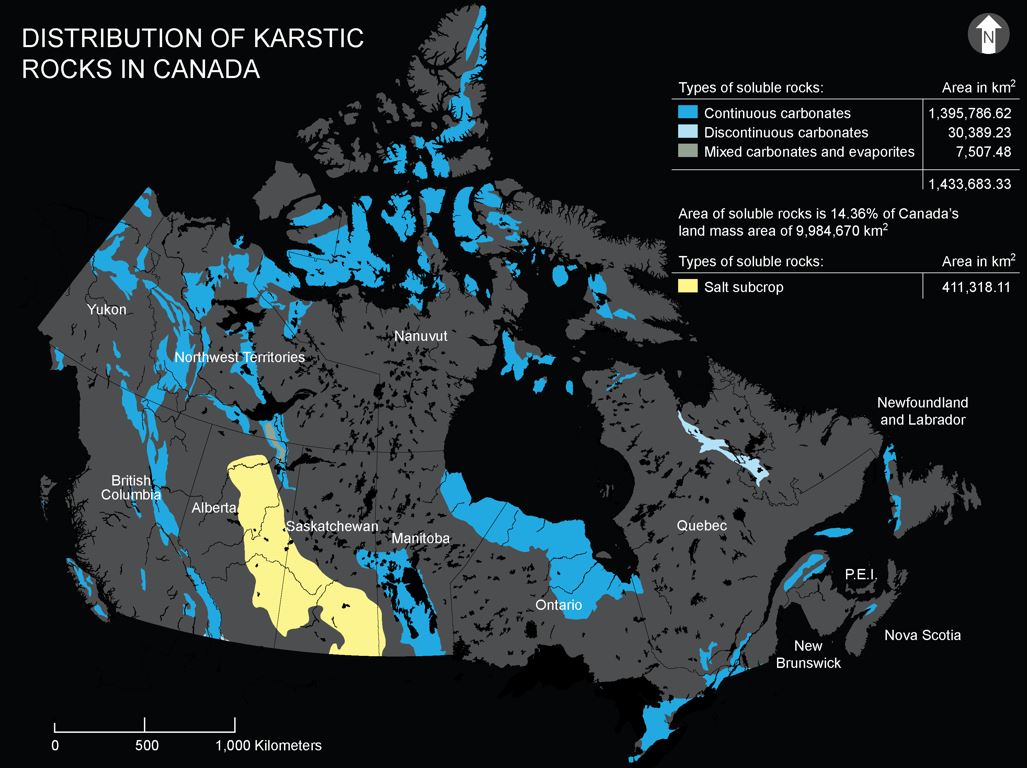

About 14% of Canada is underlain by bedrock known to have the potential to form karst. Karst is known to occur in every Canadian province and territory except Prince Edward Island.

Notable areas with karst in Atlantic Canada include Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula, Anticosti Island, and the Gaspé Peninsula (Quebec), and the gypsum karsts of southern Newfoundland, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. Examples of areas with karst in central Canada include the Niagara Escarpment, the Ottawa River Valley, and the Hudson Bay Lowlands. Manitoba has large areas of karst which also extend into part of northeastern Saskatchewan.

Large areas of southern Saskatchewan and northeastern Alberta are underlain by evaporite rocks, although these areas do not presently show much evidence of karst features on the surface. Wood Buffalo National Park in northern Alberta contains spectacular examples of gypsum karst. Large areas of karst-forming carbonate bedrock in Alberta occur along the Rocky Mountains.

Large areas of carbonate bedrock with the potential to form karst are present in Nunavut and the Yukon and Northwest Territories. The Nahanni National Park Reserve in the Northwest Territories contains fine examples of subarctic karst and has the distinction of being the world’s first UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Did you know? The Ni’iinlii Njik (Fishing Branch) Territorial Park and Habitat Protection area in the Yukon Territory contains an important karst area. Despite its location in the Arctic Circle, water from the karst remains ice free year-round. Bears are attracted to the salmon runs here as well as to the hibernation sites in the caves, which also contain important palaeontological and archaeological material.

The map above showing the distribution of karstic rocks in Canada was created using the <whymap_karst__v1_poly.shp> shapefile for carbonates and evaporites available for downloading from the WHYMAP (Worldwide Hydrogeological Mapping and Assessment Program WOKAM (World Karst Aquifer Map) project site <www.whymap.org>. The area of salt subcrops in the Prairie provinces was obtained from Figure 1 in D.C. Ford. 1997. Principal features in evaporite karst in Canada. Carbonates and Evaporites, 12(1):15–23, as subsequently published on p. 176 in: J. Gunn, ed. 2004. Encyclopedia of cave and karst science. New York and London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. Major lakes and rivers, and provincial and territorial boundaries are from various open Natural Resources Canada map data sets. The geometric reference system used for the final map illustration is NAD83(CSRS). (Illustration by P.A. Griffiths)

Karst in B.C.

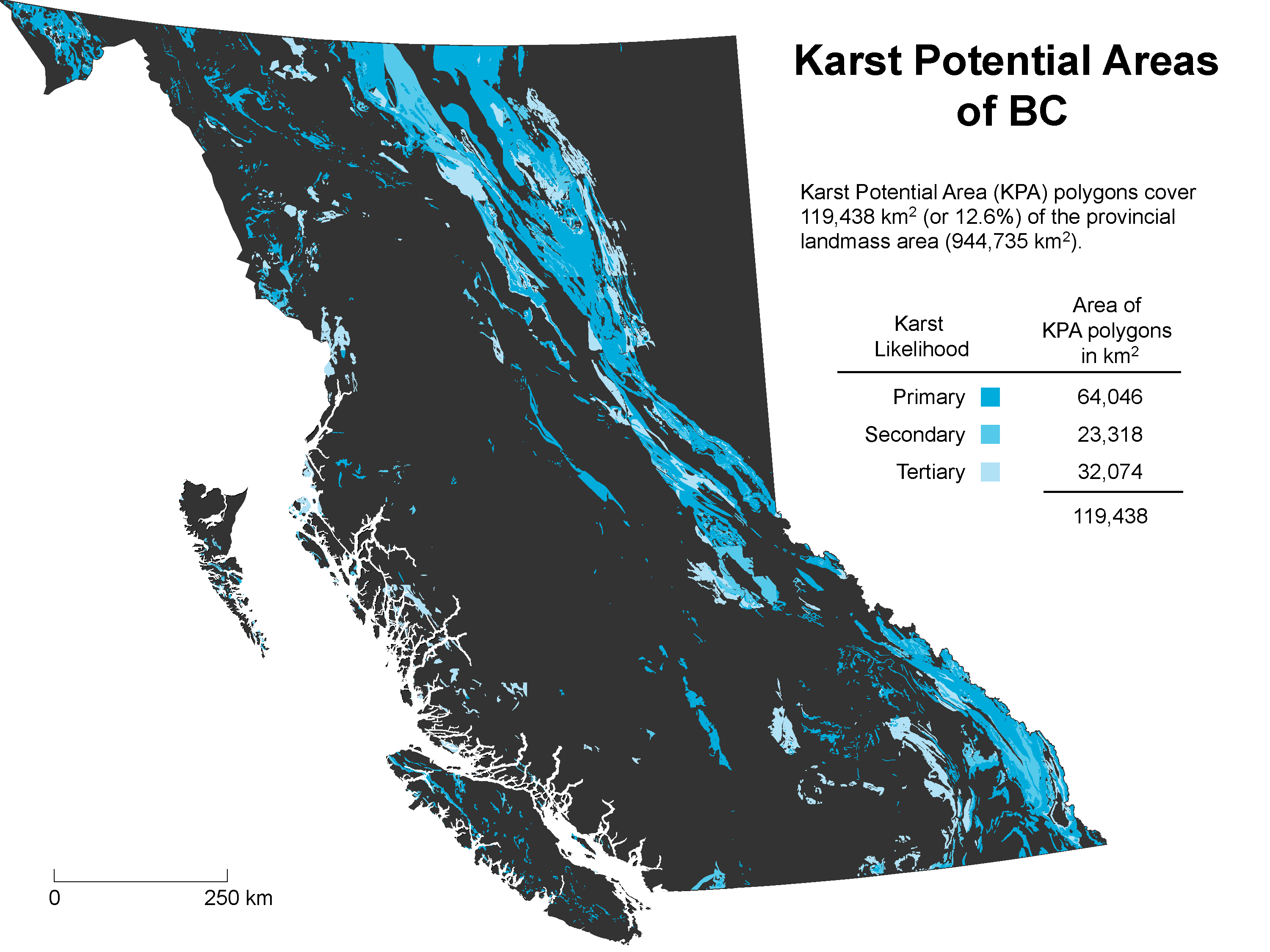

About 10% of B.C. is underlain by bedrock that has the potential to form karst. As noted previously, the presence of soluble bedrock alone does not necessarily guarantee that karst is present, so the actual areas of karst in the province will be something less than 10%.

The character of B.C.’s karst varies greatly throughout the province due to regional factors such as geology, climate, glacial history, and vegetation.

In coastal B.C., the best-known karst areas occur on Vancouver Island, Texada Island, Haida Gwaii, and parts of the mainland coast that are underlain by relatively pure limestone and marble. These areas receive a lot of rainfall through much of the year, which is one of the reasons the karst in these areas can be very well developed. In the lower elevation forested karst areas, dolines (karst sinkholes) are perhaps the most common karst features, but karst springs, sinking streams, shafts, grikes, caves, karst canyons, and fluted bedrock surfaces are not uncommon. At higher elevations, the lack of forest cover often leaves more of the bedrock exposed. Higher elevation karst is often characterized by many different types smaller-scale rocky relief features as well as deep grikes, shafts, and sinking streams.

Photo above: Karst in the Coastal Western Hemlock zone (Photo by C.L. Ramsey)

Photo above: Karst in the Mountain Hemlock zone. (Photo by C.L. Ramsey)

Photo above: Karst in the Alpine Tundra zone (Photo by C.L. Ramsey)

The interior karst areas of B.C. are typically drier and cooler in winter than those in coastal B.C.. On the surface at least, evidence of karstification in the Interior can be much less obvious than in coastal regions. There are generally fewer features, such as dolines and fluted rocky relief, but evidence of internal drainage such as karst springs and solutionally enlarged openings on canyon walls are present. Some of the better-known karst in the B.C. Interior occurs in the Marble Range in the south and the Fort St. James and Stuart Lake areas farther north.

Much of eastern B.C. is mountainous terrain with cooler winters and warm dry summers. Mountain-building processes have aided karst development in some areas by creating fractures in the rocks. There are many known caves in the Southern Rocky Mountains and Selkirk Mountains in southeastern B.C., including the Cody Caves in the namesake provincial park and the Nakimu Caves in Glacier National Park. Karst is also found in northeastern B.C. where doline fields and occasional poljes (elongated basins formed by the coalescence of several dolines) occur at higher elevations. Karst depression features, springs, small cave entrances, karst ponds, and vertical rock bluffs can be seen from some of the trail systems in Monkman Provincial Park.

Extensive and mostly forested gypsum karst areas mantled by assorted glacial sediments are found in northwestern B.C. and the Kootenay Ranges of southeastern B.C., east of the Rocky Mountain Trench. The characteristic landform features include stream sinks and related springs, caves, dolines, and other karst depressions. Many of the dolines appear to have resulted from collapse processes and some have ponded water.

Aerial photo showing examples of gypsum karst dolines near Lussier River, Kootenay Ranges, Southeastern B.C. The largest dolines are identified by the orange circles. (Image credit: Microsoft Bing Maps Aerial)

Where can I see karst in B.C.?

Many exceptional karst areas in B.C. are in remote areas that are difficult for visitors to access. Onsite karst interpretation and infrastructure in these areas may be limited or non-existent. Visitors should go prepared with sturdy footwear and appropriate clothing and stay on established trails to ensure safe viewing and maximum enjoyment. In some cases, travel on active logging roads may be required. A reliable vehicle and a good map or GPS navigation system are required in some cases.

Here are some areas where karst can be seen in B.C.:

- Cody Caves Provincial Park near Ainsworth

- Hole-In-the-Wall Provincial Park near Chetwynd

- Stone Corral Interpretive Hiking Trail in Monkman Provincial Park near Tumbler Ridge

- Horne Lake Caves Provincial Park near Qualicum Beach

- Upana Caves Interpretive Forest Site near Gold River

- Little Huson Cave Regional Park near Woss

- Karst Creek Trail in Strathcona Provincial Park on Vancouver Island

Test your knowledge

Self test (True/False)

Answer either True or False to check your understanding:

-

Bedrock mapping is a definitive source of information about where karst occurs.

-

The karst in B.C. is similar no matter where it is found in the province.

Answers

-

False. Bedrock mapping can give some indication of where karst may occur, but the presence of soluble bedrock alone doesn’t necessarily mean karst is present.

-

False. The karst of B.C. is as diverse in character as the many different biogeoclimatic zones in which it is found. Each region of the province has karst areas with unique characteristics based on the geological and climatic conditions of the area.