Lesson 4: What Values are Associated with Karst?

On this page

- Lesson objectives

- Water values

- Biodiversity values

- Geodiversity/geoheritage values

- Scientific values

- Cultural values

- Recreation and tourism values

- Education values

- Economic values

- Indigenous values

- Where can I learn more about karst values?

- Test your knowledge

Lesson objectives

Lesson 4 introduces the many different values associated with karst. By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- List nine categories of values that are associated with karst landscapes or systems

- Give specific examples of karst values in each of these categories

- Explain why these values are important

Water values

Water is one of the most important values associated with karst globally. Although only 7 to 10% of the Earth’s ice-free land surface is estimated to be karst, it provides drinking water to about 25% of the world’s population. The city of Vienna, Austria, for example, relies on karst for its drinking water.

B.C. has an abundance of fresh surface water, so only a small percentage of people in the province rely on karst aquifers for their drinking water. In B.C., water from karst systems may be more important for aquatic productivity in streams, and by extension, fisheries and wildlife. In recent years, there have been examples of firefighters using water from karst springs to fight wildfires.

Biodiversity values

In many non-karst landscapes in B.C., living things are associated with forest canopies, vegetation cover, forest litter, soil, and streams. In karst, there is an additional extensive subsurface dimension where communities of small aquatic and non-aquatic organisms occur.

A wide variety of unusual and sometimes extreme conditions related to the physical structure of the karst and its geochemistry can be present within even a small area of karst. Specialized adaptations may be required for organisms to colonize such spaces. The result is that karst is recognized as a biodiversity “hotspot” and tends to have rare or unusual species on the surface and in the subsurface. Distinctive plant assemblages may occur due to higher pH values and the usually well-drained nature of karst.

High levels of biodiversity in surface karst areas may be partly linked to the physical heterogeneity or geodiversity that is typical of karst landscapes. For example, within a few metres, habitats may range from thinly soiled, sun-baked epikarst exposures and karst outcrops to cool, moist semi-dark zones in the bottom of deep grikes.

Cave entrances, springs, and dolines (karst sinkholes) are important surface-subsurface transition zones that often have distinctive microclimates. Their microclimates can be influenced by the relatively stable temperature and humidity of the karst subsurface. Animals may use these transition areas in different ways. For example, deer are often seen resting in the bottoms of dolines. Other fauna may be observed in cave entrances which can be cooler or warmer relative to surface temperatures.

Some of the greatest biodiversity in karst is found underground. Although animals that live in B.C. caves and epikarst have not been well studied, more intensive research into underground organisms has been undertaken in other parts of the world. Such studies often discover animals previously unknown to science. In recent decades, there has been an increased awareness and interest in the communities of organisms that inhabit the small cracks and fissures within the epikarst.

A variety of different fauna can be found underground, some of which are aquatic. Others are visitors that have entered or fallen into caves by accident or use caves seasonally – for example, harvestmen (that is, daddy long-legs) seem to congregate in some caves in coastal B.C. over the winter, while some bats may use caves for hibernation. Cave crickets can live in caves year-round although they may venture outside to forage.

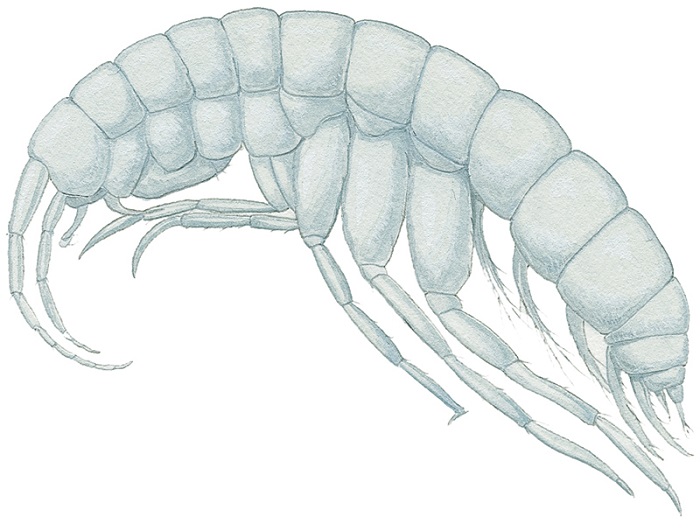

Some faunae are adapted to spend their entire life underground – an example is the amphipod Stygobromus quatsinensis that lives in the water-filled parts of caves and epikarst on Vancouver Island and Southeast Alaska. It shows some of the characteristics, no eyes and pale colouring, that are typical of cave-adapted organisms.

Did you know? Limestone or dolomite pavements or “alvars” are home to biodiverse and globally rare ecosystems that often contain rare, endemic, or threated species of plants and animals?

Alvars are currently only known to occur in parts of northwestern Europe – Sweden, Estonia, Ireland, and parts of the United Kingdom – as well as in the region of the Great Lakes Basin in North America, and in parts of Manitoba, Québec, Newfoundland, and the Northwest Territories.

Alvars typically experience environmental extremes – from extreme heat to extreme cold, and from flooding to drought. They typically have sparse soils and hence usually support few if any trees.

The rare and biodiverse communities these alvars support are particularly sensitive to disturbances from human land-use activities. Trampling of the vegetation, impacts from grazing or vehicle traffic, the introduction of invasive species, and a variety of development activities can all have adverse effects.

The biodiversity value of alvars is being increasingly recognized in areas where these special ecosystems are known to occur.

Geodiversity/geoheritage values

Geodiversity and geoheritage values of karst include features and landforms on the surface of the karst as well as the subsurface. As noted in the previous lesson, the form karst takes and how quickly it develops depends on a combination of factors such as climate, bedrock chemistry and physical properties, geological history (including plate tectonics, folding, faulting and glaciation), and vegetation cover through time. Underground, cave sediments and speleothems can contain information about past climates, landscape evolution, and even early human activities. In this sense, karst landscapes can represent exceptional examples of an area’s geoheritage.

The diversity of karst landforms can range from level surfaces, such as the bottoms of large poljes of the Dinaric Karst or the karst pavements of the Burren in Ireland, to the jagged pinnacle karst of Madagascar’s Tsingy de Bamaraha or China’s Shilin Stone Forest, to the water-filled cenotes of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

Surface karst features vary not only in terms of their shape, but also their size. Features like poljes, planation surfaces, and blind valleys can range in size from a few metres to a kilometre or more. By contrast, small-scale rocky relief features such kamenitzas (small solution pans) or fluted karren can be measured in centimetres.

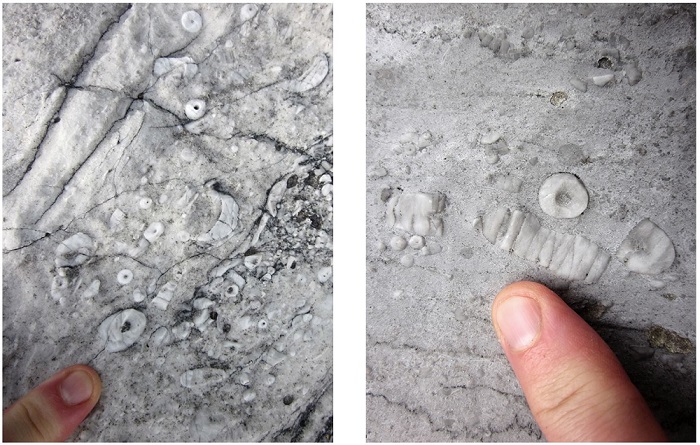

Photos above: Crinoid (“sea lily”) fossil in limestone near Buttle Lake in Strathcona Provincial Park on Vancouver Island. Such fossils are an example of the geoheritage value of karst. (Photos by C.L. Ramsey)

Scientific values

Karstology is the scientific study of karst or some aspect of karst. The earliest scientific roots of karstology can be traced to geography, geomorphology (landforms), and hydrology, but today these areas of study have been integrated into the scope of modern karstology and have become specialized areas of research within the field of karst science. Karstology today integrates many other fields of study (for example, biology, ecology, chemistry, history, sociology) and is a recognized scientific discipline.

There are several research institutes dedicated to the scientific study of karst around the world, including the Karst Research Institute in Postojna, Slovenia and the Institute of Karst Geology in Guilin, China. Other research institutes, such as the laboratoire Environnements, Dynamiques et Territoires de la Montagne (EDYTEM) at the University of Savoie Mont Blanc in Chambéry, France, incorporate karst research as part of a broader approach to environmental science.

Some karstologists specialize in very specific areas of study like karst geomorphology, karst hydrology, karst ecology, animals that live in the epikarst, or small-scale rocky relief features. Others study cave sediments that can sometimes be used for environmental reasons or reconstructing episodes in a cave’s history. Still others take a more generalist approach and may focus more on applied research or the social, cultural, or historical aspects of karst.

Other scientists from fields unrelated to karstology may study things that are sometimes associated with karst. Examples include botanists interested in rare or endemic plants, palaeontologists or archaeologists who study ancient animal remains or evidence of human culture preserved in caves or rock shelters, and biologists conducting bat research.

Scientists from unrelated fields sometimes collaborate with karstologists. For example, astronomers may want to understand how karst-like landforms observed on other planets form.

Did you know? Speleologists are scientists who study caves or some aspect of caves. Speleology differs from karstology in that its focus is on the subsurface; however, there are some obvious overlaps with karstology and there is usually a collaborative relationship between the two disciplines.

Some speleologists study speleothems, which are mineral deposits in caves; others study cave fauna, cave climates, or the structure and geometry of the caves themselves. Researchers are looking for new pharmaceutical compounds or studying chemical signatures (isotopes) in stalagmites (icicle-like calcium carbonate deposits on the floors of caves) to reconstruct past climates. Others study how the sensory deprivation and isolation of living in underground environments affects human physiology, psychology, or sleep patterns.

Cultural values

To some extent, landscapes shape cultures in as much as they dictate what is possible in given locations. Karst can influence settlement patterns; for example, in dry karst landscapes, early human settlements might have been situated around springs that provided fresh water for humans and livestock, or rock shelters that offered protected living spaces. Some of the types of bedrock that can host karst – such as limestone or marble – provided the raw materials for settlement buildings as well as sculpting.

Photo above: Detail of the Mozart Monument, a marble sculpture by Victor Tilgner, located in the Innere Stadt District of Vienna, Austria (Photo by C.L. Ramsey)

Thin rocky soils can limit the potential of some karst landscapes for growing food crops and influence the types of food that can be produced, as well as where and how foods are produced and processed. For example, in parts of the Dinaric Karst, which borders the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea between the Gulf of Trieste and the Drim River in Albania, the land is too rocky to support field crops, so gardens were situated in the bottoms of dolines (karst sinkholes).

Photo above: Garden situated in the bottom of a doline. Rocks were collected and used to build drystone walls around the doline to keep grazing animals out. (Photo by C.L. Ramsey)

Some karst landscapes, such as the iconic feng cong tower karst of Guilin, China, are inseparably intertwined with a region’s identity, culture, and arts. Others, such as the huge rock shelters of France’s Vézère Valley, provided living sites for early humans and continue to attract visitors today. Some of the earliest known examples of art are preserved in karst caves, including the caves of Altamira in Spain, and Chauvet and Lascaux in France.

Caves have inspired reverence or spirituality in people in many parts of the world – a well-known example is the grotto at Lourdes, France. People continue to use caves for these and other purposes, including dwellings or spaces for ripening cheese, storing food, or socializing.

Some parts of the world have distinctive “karst cuisines” or foods and beverages produced in karst areas. Prized regional products (or “terroirs”) such as pršt (the air-dried “karst ham” of Slovenia), some wines, cheeses and bottled spring waters, and the swift nests used in birds nest soup are examples of famous food products associated with karst. Karst cuisines or terroirs can sometimes be linked to karst tourism.

Photo by C.L. Ramsey

Photo by C.L. Ramsey

Recreation and tourism values

Many people immediately think of caving when they consider karst and recreation. Yet owing to the sensitivity of some caves to disturbance, caving is not necessarily the most environmentally sound or sustainable form of karst recreation. There is growing recognition that careful study and planning is needed to ensure the sustainable development of surface and subsurface karst tourism and recreation sites.

Recognizing the need to promote more sustainable cave tourism, many important show caves, such as the Škocjanske Jama World Heritage Site in Slovenia, have implemented comprehensive management plans and monitoring programs to minimize the impacts caused by large groups of visitors.

There are many fine examples of surface-based karst recreation and tourism sites that draw visitors from around the world. Examples include the spectacular lakes, waterfalls and tufa dams of Croatia’s Plitvice Jezera and the scenic alpine karst along Austria’s 8-km long Dachstein Plateau Nature Trail. France’s Ardèche Gorge is a karst area well known for kayaking and canyoning.

An excellent example of a sustainable surface karst recreation and tourism site closer to B.C. is the Beaver Falls Karst Trail on Prince of Wales Island in Southeast Alaska. It consists of an accessible 2.4- km long yellow cedar boardwalk loop through forested karst with excellent science-based karst interpretation providing clear, simple explanations about the karst, including its sensitivity. Visitors are not prevented from entering the caves but are encouraged to carefully weigh the implications of doing so.

Did you know? In some parts of the world, it is possible to visit “replica” caves that closely mimic the experience of visiting real caves – without impacting the real caves. Two examples of this are: 1) Grotte de Lascaux, and 2) the Caverne du Pont-d’Arc, the realistic replica of the famous Grotte Chauvet that contains spectacular cave paintings dated around 35-40,000-years old.

France had previous experience with some of the problems that can evolve when such caves are opened to the public, notably with Grotte de Lascaux, a famous painted cave discovered in 1940. The subsequent development of infrastructure and the large numbers of visitors changed the cave environment such that the paintings started to deteriorate. As a result, Lascaux has been closed to the public since 1963. Visitors to one of the three impressive replicas can now enjoy an experience so closely approximating a visit to the real Grotte de Lascaux that some visitors do not realize that they have visited a replica cave.

To preserve Grotte Chauvet, the cave was never opened to the public. Instead, recognizing its international significance and appeal, the French government created a spectacular faithful replica cave called the Caverne du Pont-d’Arc (also known as “Chauvet II”). This replica is astonishingly accurate in almost every respect – even mimicking the temperature, sounds and humidity of the real Grotte Chauvet.

Did you know? Butchart Gardens, one of B.C.’s most popular tourist attractions draws nearly a million visitors from all over the world every year. This important tourist attraction is based in an old limestone quarry outside of Victoria. Most visitors are not aware that there is evidence of karst development in some of the quarry walls.

Education values

In some cases, karst recreation values can be combined with educational values. Good site interpretation can enrich visitor experiences to karst sites. Karst provides many educational opportunities for people of all ages who are interested in learning more about the natural world.

Economic values

There are many uses for limestone. It is used in products such as cement, toothpaste, and paper. Marble is often used for countertops and tiles and is valued as a medium for sculptures.

Karst landscapes are sometimes used in commercial film production because of their scenic or other-worldly characteristics – for example, part of Lord of the Rings was filmed in karst in New Zealand. Karst sites have also been used for commercial filming on Vancouver Island.

As noted in the recreation and tourism section, many karst areas around the world have thriving tourism economies. Many natural and cultural world heritage sites are situated in karst areas. Visitors are attracted by the scenery, recreation opportunities, or aspects of the culture or gastronomy.

Kayaking is one recreation activity that can be associated with karst. (Photo by P.A. Griffiths)

Indigenous values

As the archaeological evidence suggests, karst played a significant role in the lives of many Indigenous Peoples in the past. Karst caves were not only used for shelter but were also considered by some groups to be sacred places for burial and ceremonial purposes.

Unusual limestone surface features often played a role in Indigenous mythology, and the water from karst springs was viewed as having special properties. In many cases, the productivity of karst terrain also benefited Indigenous Peoples by supplying large trees for dugouts, construction materials, or totem poles, and by providing excellent growing sites for various shrubs and herbs used for food and medicines.

Many present-day Indigenous cultures continue to value karst for ancestral, heritage and cultural reasons.

Where can I learn more about karst values?

You can learn more about the values associated with karst from the following sources:

- Karst in B.C. - A Complex Landscape Sculpted by Water

- Pages 6 to 12 of the Karst Management Handbook for British Columbia

Test your knowledge

Self test (True/False)

Answer either True or False to check your understanding:

-

From a management perspective, caves are the most important parts of karst systems.

-

From a management perspective, the water in B.C. karst systems is of lesser importance given the abundance of fresh surface water in the province.

Answers

- False. Karst management in B.C. focuses on managing karst systems, not just caves. It is true that caves are important karst features and may require special management such as for tourism, cultural, or biodiversity reasons. However, from a karst management standpoint, caves are just another component of a karst system. If present, caves cannot always be singled out as the most important parts of a karst system, nor can they be managed as if they were isolated from the other components of karst.

- False. B.C. has abundant fresh surface water from non-karst sources. However, the health and productivity of downstream aquatic systems and fisheries can often depend in part on the quality and quantity of water from karst systems.