Asthma Diagnosis, Education and Management

Effective Date: July 26, 2023

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Navigation

- Key Recommendations

- Epidemiology

- Risk Factors

- Diagnosis

- Differential Diagnosis

- Management

- Resources

- Appendices

Scope

This guideline provides recommendations for the diagnosis, education, and management of mild – moderate asthma in the primary care setting, for both pediatric and adult patients. It replaces two previous BC Guidelines, Asthma in Adults (2015) and Asthma in Children (2015).

Severe asthma and severe exacerbations are out of scope of this guideline.

Navigation

Most asthma diagnosis and management information is consistent across patient age ranges. However, there are some age-specific diagnostic and medication considerations, identified in the circles next to each section.

Key Recommendations

Diagnosis

- A positive response to a therapeutic trial of salbutamol following an office visit in which the patient presents with audible wheeze is sufficient for a presumptive diagnosis under age 6.

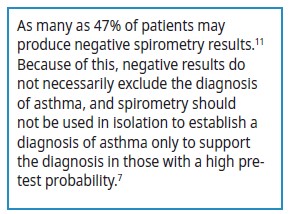

- Confirmation with spirometry remains the gold standard for patients over age 6.

Medication

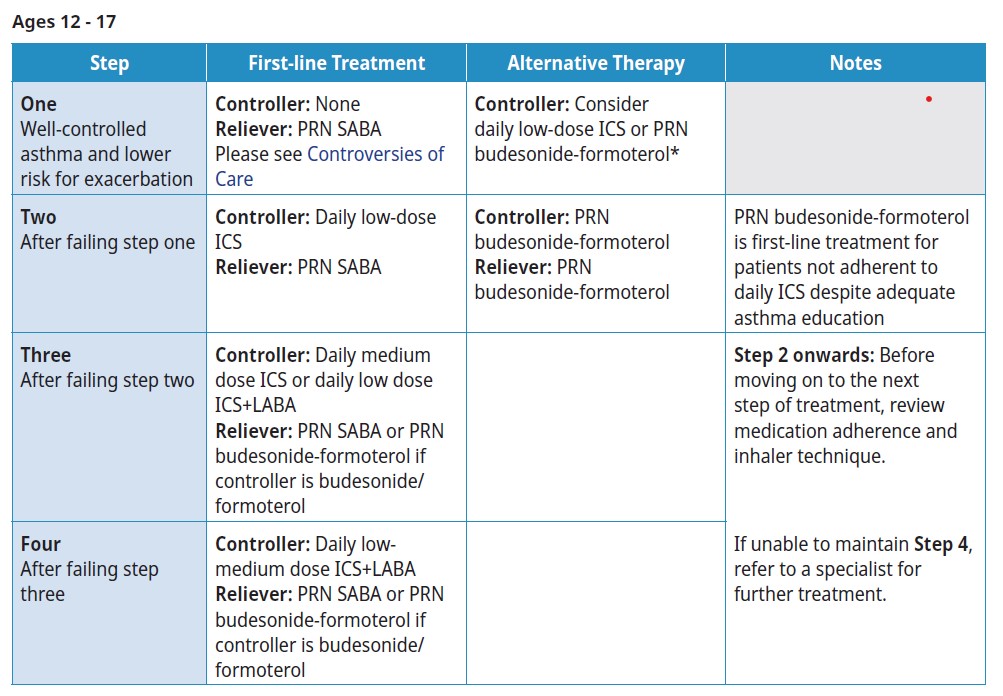

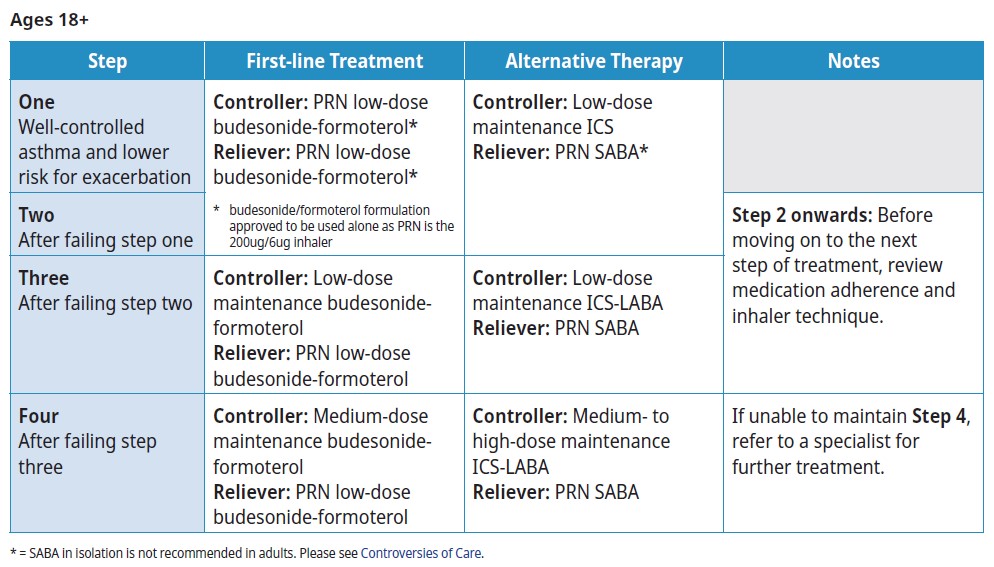

- PRN Budesonide formoterol is recommended as first-line for adults with very mild asthma.

- PRN short acting beta agonists is recommended as first-line for children with very mild asthma who are at lower risk for exacerbations.

- Daily inhaled corticosteroids are recommended as first-line for children with very mild asthma who are at higher risk for exacerbations.

- Assess a patients asthma management before prescribing systemic steroids. Significant adverse events are associated with as few as 4 short courses of systemic steroids in a lifetime.

- Begin with the step most appropriate to the initial severity of the patient’s asthma.

- Reassess asthma control and exacerbation risk at least every 6 months and decrease medication doses to the lowest effective dose.

Management

- Develop a written asthma action plan with all patients and/or family. Reassess regularly.

- Confirm patient is using inhalers correctly and as prescribed, especially when there is a non-response to treatment.

Environmental Impact and Climate Change

- Consider lower-environmental impact medication options where appropriate as metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) contribute disproportionately to climate change, which in turn can affect asthma.

- Prepare for climate events such as wildfire, which can exacerbate asthma.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of asthma in BC has increased steadily over the last 20 years:1, from 8% of British Columbians in 2001/02 to (12%) in 2021/22.2 In 2015, asthma exacerbations resulted in 70,000 hospitalizations and 250 deaths nationally.3,4 Disease management and primary care follow-up after an acute care episode are key to reduce hospital visitation.5

As children grow older and hospitalizations become less frequent, the overall direct cost decreases. The highest cost for asthma care is for individuals with severe or uncontrolled asthma.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for developing asthma include but are not limited to:6

- Family history

- Allergies

- Exposure to poor air quality

- Early viral respiratory infections

- Obesity

Diagnosis

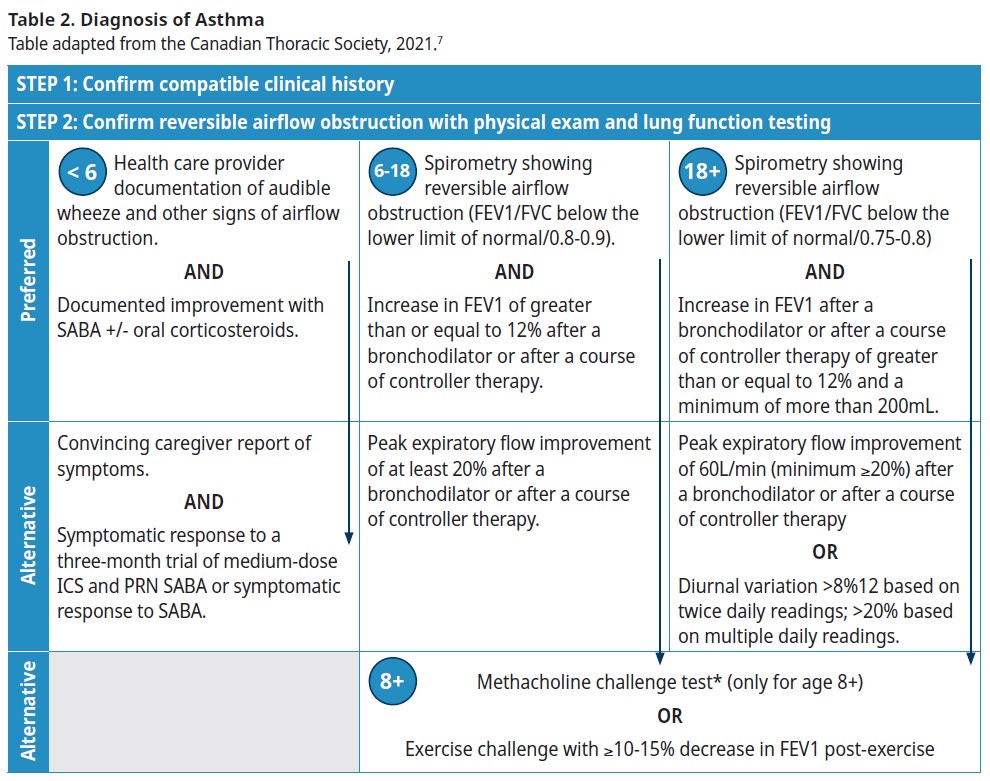

An asthma diagnosis is based on both a clinical history and physical examination compatible with asthma and objective evidence of reversible airflow obstruction.7

In patients with an existing asthma diagnosis, ensure there is documented evidence of variable airflow obstruction. See Table 2. Diagnosis of asthma for an overview of the diagnostic criteria of asthma by age.

History and Physical Examination

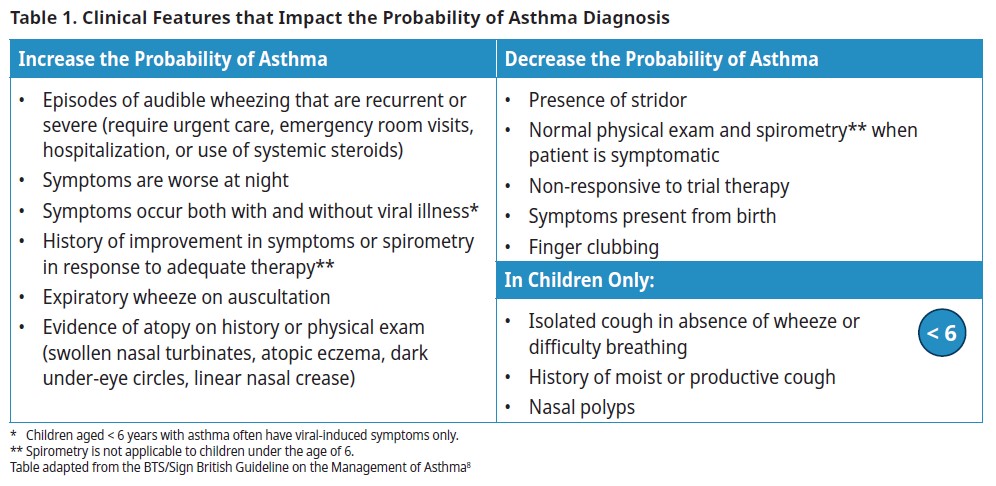

Clinical features of asthma (see Table 1. Clinical features that impact the probability of asthma diagnosis) often mimic or overlap with other respiratory conditions. Ensure other possible diagnoses are considered before diagnosing a patient with asthma (see Differential Diagnosis).

Wheezing

Wheezing is the most specific sign of asthma. As there are many types of sounds patients may describe as ‘wheezing’, this should be clarified and ideally confirmed on physical exam. The wheezing associated with asthma is a high-pitched whistling sound, typically heard on expiration.

Adults are less likely to present with auscultative wheeze.

Adults are less likely to present with auscultative wheeze.

Non-wheezing Symptoms

Other symptoms associated with asthma include chest tightness, dyspnea, and cough.7 Patients who report more severe symptoms upon waking or overnight are more likely to have asthma.9

Note that signs and symptoms can be transient in nature and may not be present during the physical exam.

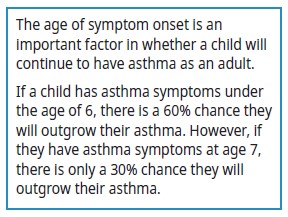

Diagnostic Considerations for Children Under 6

Diagnostic Considerations for Children Under 6

Children under the age of 6 years with asthma often have viral-induced symptoms only. Other triggers include irritants, allergens, and exercise.

Since children under the age of 6 cannot do spirometry reliably, the diagnosis of asthma is based on physical exam findings and response to medication as objective evidence of reversible airflow obstruction. Once they reach the age of 6, the diagnosis can be confirmed with spirometry.

Spirometry (Age 6 and Over)

Spirometry (Age 6 and Over)

Spirometry is a test performed to assess an individual’s pulmonary function. It can be used to establish a diagnosis, monitor disease progress, or evaluate the effect of therapeutic interventions.10

Spirometry is most accurate when a patient is symptomatic. Consider a patient’s medical history, including any recent hospitalizations.

Caregivers and children may have questions about what to expect at a spirometry appointment. Please see Appendix A: Getting Ready for Spirometry.

Spirometry in the Office

Spirometry in the Office

For spirometry to qualify for coverage under the Medical Services Plan, testing must be performed at an accredited facility. However, evidence suggests that with correct training and equipment, spirometry performed in a family physician's office is comparable to testing performed in a pulmonary function laboratory in adults.12

Second Line Tests

When spirometry results are negative and clinical suspicion remains, the following tests may be helpful in diagnosing asthma:

Methacholine Challenge (Age 8 and Over)

Methacholine Challenge (Age 8 and Over)

If spirometry is normal and asthma is still suspected, methacholine challenge (MCC) or an exercise challenge can be done.7 It should be considered if an individual is not responding to standard asthma therapy (see Indications for Referral). MCC is useful for ruling out a diagnosis of asthma in a symptomatic patient.13

This test is lengthy and requires a child to be able to do spirometry consistently, so it is typically not possible in children under the age of 8.

Peak Flow Monitoring (PFM)

Peak Flow Monitoring (PFM)

PFM may be useful in providing objective evidence of variable airflow obstruction when:

- Evidence is needed quickly, and spirometry is unavailable (e.g., geography and access issues)

- In suspected cases of work-related asthma where PFM can be used at the workplace; and

- A patient is symptomatic, and they have baseline peak flow readings for comparison (see Associated Document –Asthma Action Plan)

Spirometry is the preferred test as reference values for peak flow readings are not as well standardized, readings are more variable, and the device may malfunction.

Remember to use the same meter is used for PFM as readings can vary substantially by device.

Other Tests: Allergy Testing

For patients whose symptoms are not well controlled and have symptoms seasonally or with exposure to certain inhaled allergens, it may be helpful to identify which allergens a patient is sensitized to. Although allergy testing for inhaled allergens can be done at any age, allergens are more likely to cause symptoms after age 4 for indoor allergens and after age 5 for outdoor allergens.14

Inhalant allergen exposures have been shown to lead to asthma attacks in some patients. It is rare for food allergens to cause asthma symptoms unless the allergenic protein is aerosolized and inhaled, or the patient is having anaphylaxis.9

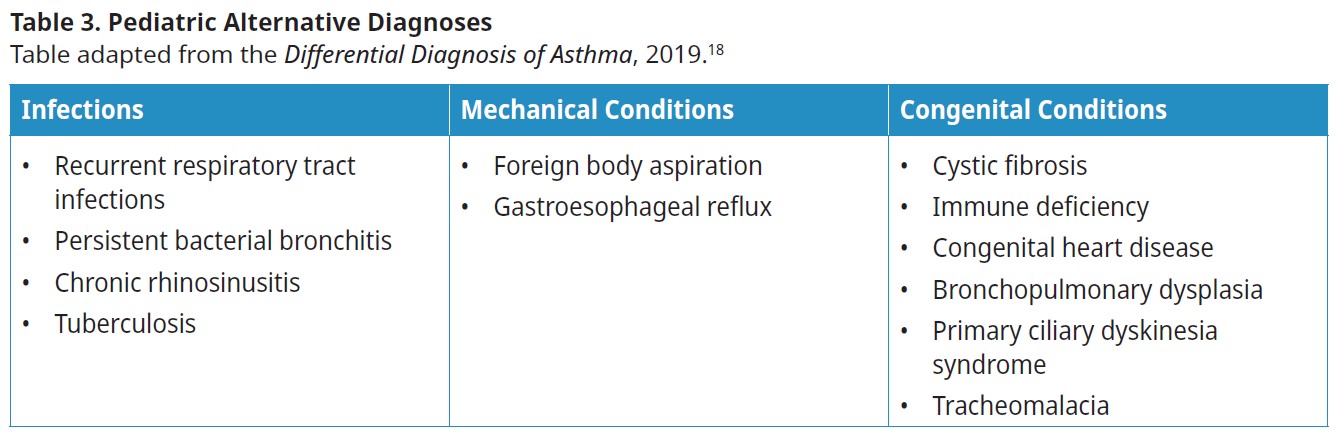

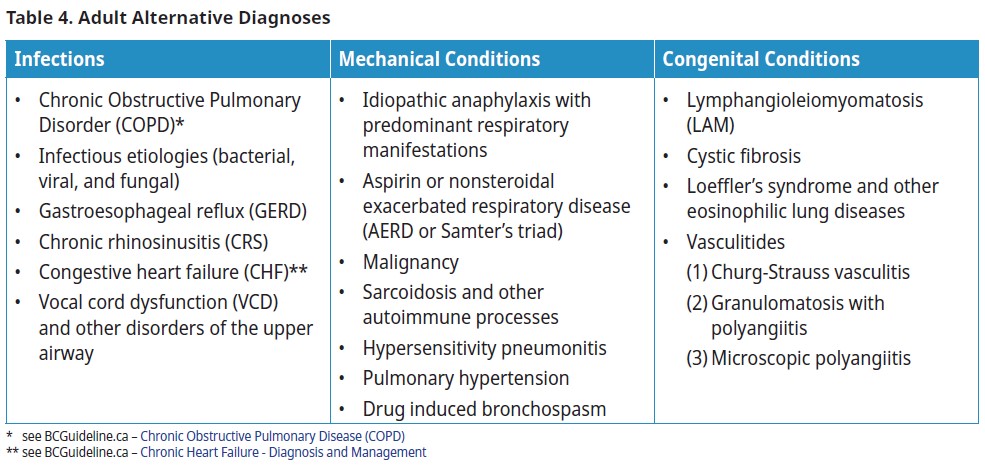

Differential Diagnosis and Misdiagnosis

Up to 30% of patients with a physician diagnosis of asthma are misdiagnosed.15,16,17 Spirometry is the best first-line test for diagnosis and should be pursued to avoid misdiagnosis. In those that do not respond well to treatment, assuming adherence, inhaler technique and co-morbidities are being treated, reconsider the diagnosis with clinical correlation and obtain objective evidence of variable airflow obstruction.

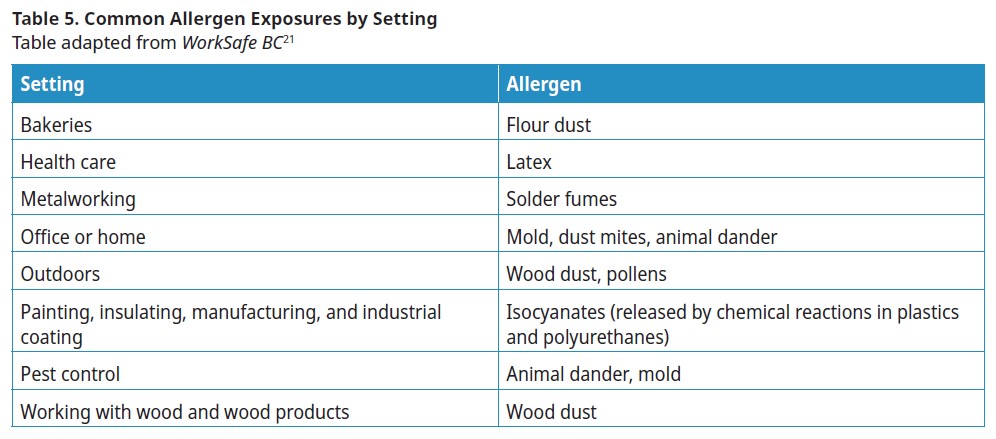

Work-Related Asthma

Work-Related Asthma

Work-related asthma includes both occupational asthma (asthma symptoms that are a result of exposure to workplace irritant/allergen) and work-aggravated asthma (pre-existing asthma symptoms that worsen due to exposure of workplace irritant/allergen).19

Ask all adult patients about potential occupational exposures at the workplace.15,20 Refer all patients with suspected work-related asthma to a specialist. See WorkSafeBC for more information.

Management

The core components of asthma management are:7

- Assessing control and risk of exacerbation

- Providing asthma self-management education, including a written action plan

- Identifying triggers and discussing environmental control (if applicable); and

- Prescribing appropriate pharmacological treatment to achieve and maintain control.

1. Assessing Control and Risk

Once the patient’s asthma diagnosis is confirmed (or highly probable):

- Assess the patient’s asthma symptom control

- Assess the patient’s risk for exacerbation9 and,

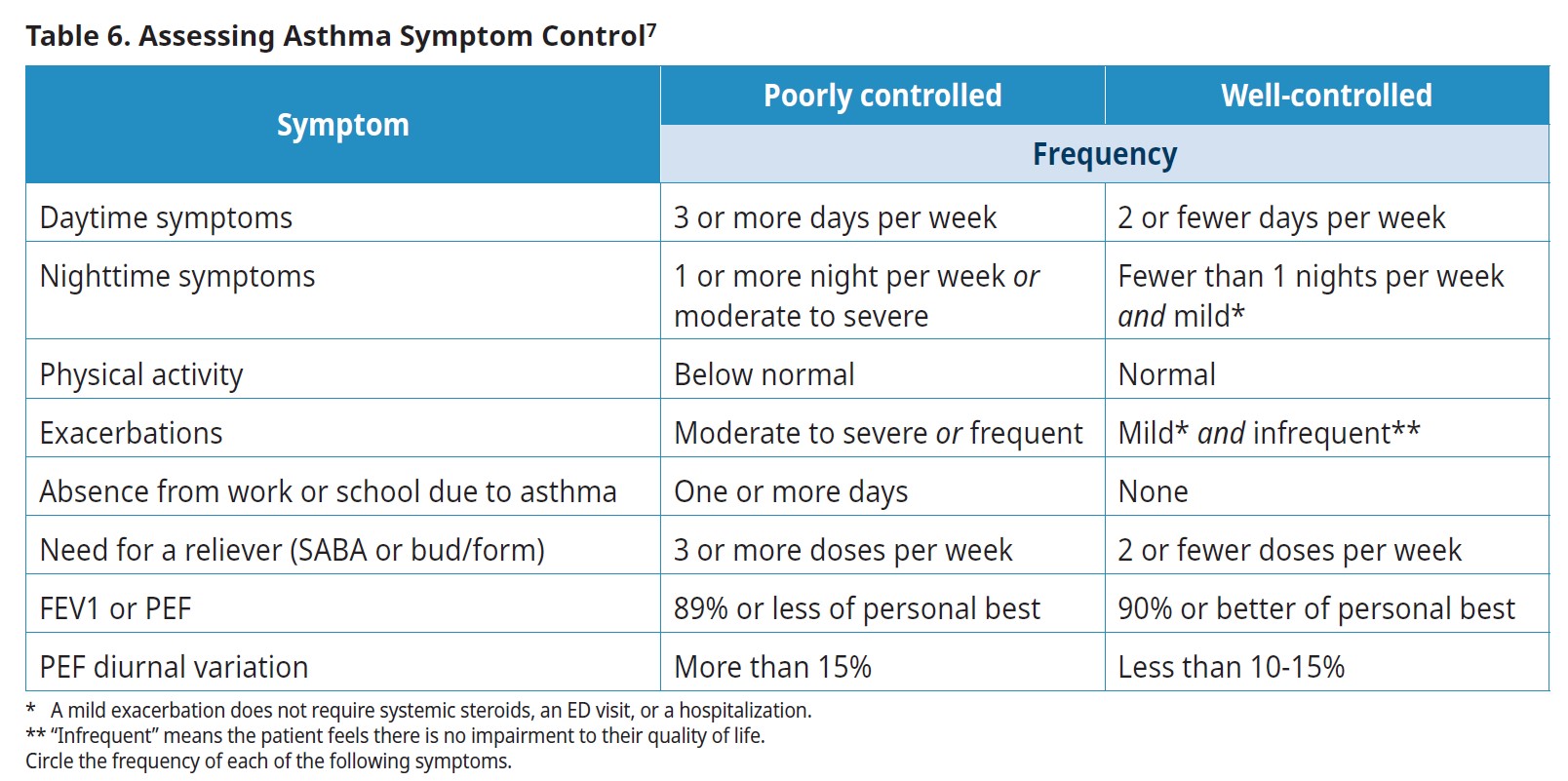

- Create/modify the patient’s treatment plan – see Table 6: Assessing asthma symptom control.

A patient with well-controlled asthma will have no symptoms as listed in the poorly controlled column of Table 6.7

A patient is at higher risk for asthma exacerbations if they have any of the following risk factors:

- Previous history of severe asthma exacerbation (requiring systemic steroids, emergency department visit or hospitalization)

- Poorly controlled asthma

- Overuse of SABA (filled more than 2 SABA inhalers in the last year)

- Current smoker

Asthma Severity

Asthma severity can only be assessed retrospectively, after a patient has well-controlled asthma for at least 3 months.9 Severe asthma is rare, constituting 3.7% of the total asthmatic population.9 It is more common to have patients with poorly controlled asthma due to poor adherence to daily medication or issues with inhaler technique.

Asthma severity classifications have changed and no longer include the terms persistent or intermittent as asthma is a chronic disease even though the symptoms may be intermittent. Severity classifications range from very mild to severe:7

- Very mild: Patient is well-controlled on PRN SABA

- Mild: Patient is well-controlled on low-dose ICS (or LTRA) and PRN SABA or PRN bud/form.

- Moderate: Patient is well-controlled on low dose ICS +second controller and PRN SABA, or moderate doses of ICS +/- second controller medication and PRN SABA, or low-moderate dose bud/form+ PRN bud/form

- Severe: High doses of ICS +second controller for the previous year or systemic steroids for 50% of the previous year to prevent it from becoming uncontrolled or is uncontrolled despite this therapy.

2. Self-management Education and Written Action Plans

Establish what the patient already knows about asthma, and then discuss:

- The condition (e.g., asthma as a chronic condition, how asthma attacks occur

- Goals of treatment (e.g., what well controlled asthma looks like, patient and/or caregiver’s concept of quality of life) and

- Treatment options (e.g., patient’s and/or caregiver’s willingness to use pharmacological therapy and trigger identification and possible lifestyle/environmental modifications) See Appendix B: Supporting Patients with Poor Medication Adherence.

After this conversation, develop a written asthma action plan with the patient and/or caregiver(s) (see Asthma Action Plan). Also refer the patient to an asthma education program, if available. Online resources, including the Provincial Health Services Authority’s (PHSA) Guide for Families and Caregivers video, may be useful. See Physician and Patient Resources.

Supporting Patients with Poor Asthma Control

Approach poorly controlled asthma gently, as the patient (or caregiver) may be reluctant to admit to cost concerns, forgetfulness, or physical barriers (e.g., arthritis) that impact adherence to their medication and/or treatment plan.

For additional information on identifying and supporting patients with poor medication adherence, please see Appendix B: Supporting Patients with Poor Medication Adherence.

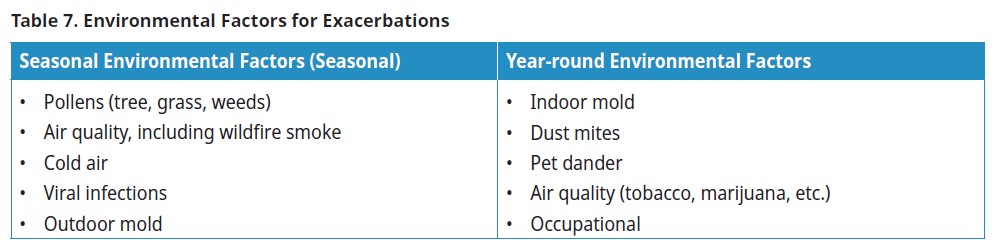

3. Identifying Triggers and Discussing Environmental Control

Environmental factors that trigger a patient’s asthma should be identified on their history and avoided, if possible. For adults, consider the work environment as well.

Smoking Cessation

Active Smoke

Active smoking is associated with increased risks of poor asthma control, hospitalizations, declining lung function, and reduces effectiveness of inhaled and oral corticosteroids.9 Encourage smokers to quit at every visit and link smoking cessation to the patient’s own, self-identified health goals. Please see the Resources in this guideline and BC Guidelines: Tobacco Cessation.

Passive Smoke

Exposure to passive smoke increases the risk of poor asthma control and may contribute to hospitalization. Advise the parents and caregivers of patients with asthma not to smoke, but if they are unable or not ready to quit, not to smoke around their children, or in any vehicles or rooms with their children.

Wildfire Smoke

Wildfire exposure is of particular concern in BC, where the frequency and size of wildfires has increased in recent years.22 Exposure to wildfire smoke and debris contributes to increased physician visits, emergency room visits, hospitalizations, frequency of respiratory infections, and all-cause mortality.23-28

Exposure to wildfire smoke is also associated with increased dispensing of rescue inhalers,24 a marker for worsening asthma control.

Wildfire Smoke and Children with Asthma

Wildfire Smoke and Children with Asthma

Exposure to wildfire smoke and ash is especially risky for children because their lungs are still developing.29

Minimizing Exposure to Wildfire Smoke

During a wildfire, patients with asthma can minimize the risk of exacerbation by:30-31

- Paying attention to local air quality reports (see Air Quality and Wildfire Resources)

- Closing doors, windows, and fireplace dampers

- Using a portable air cleaner in one or more rooms

- Using air conditioners on the recirculation setting so outside air will not be moved inside and

- Avoiding exercising outdoors.

Environmental Interventions

Evidence supporting interventions around environmental control is lacking.13 Two or more single-component interventions are more effective than a single intervention alone.13 Interventions include:

- HEPA filters

- Avoiding cleaning products

- Pest and rodent control

- Carpet removal

- Minimizing pet allergens, e.g., isolate pet to a specific area of the house.

4. Prescribing Appropriate Pharmacological Treatment

Asthma medications generally fall into one of the three following categories:

- Controller medication: Used to reduce airway inflammation, control future symptoms, and reduce future risks of exacerbation. Controllers must be maintained.

- Reliever medication: For as-needed treatment of breakthrough symptoms.

- Biologics therapies for patients with severe asthma: These medications are prescribed by asthma specialists. See Biologics below.

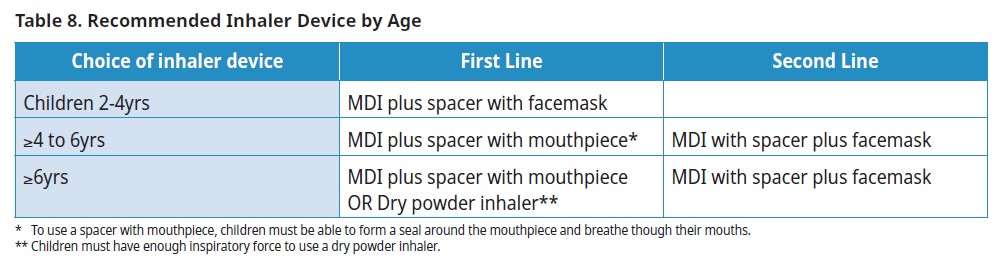

Choice of Device

The most important factor in selecting a medication delivery device is to ensure the patient can use it properly.

Pressurized Meter Dose Inhaler (MDI)

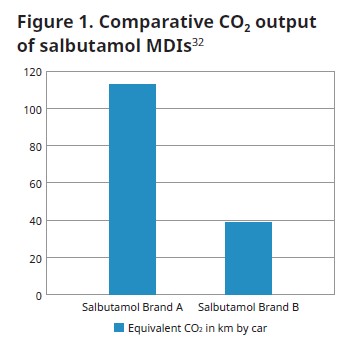

A pressurized cannister in a plastic holder with a mouthpiece. Metered dose inhalers rely on a propellant to distribute medication. The propellant is a liquefied, compressed gas called hydrofluoroalkane (HFA). HFAs have been identified as a gas with “a high global warming potential”.19 MDIs contribute significantly to healthcare’s overall carbon footprint.32

In BC, over 1.7 million inhalers are dispensed every year. In 2021, this contributed about 22,000 tonnes of CO2e or the equivalent of driving 86 million km in a standard gasoline powered vehicle. That’s 14,000 cars driven from Vancouver to Halifax. Of these greenhouse gas emissions, virtually all are caused by MDIs – yet MDIs represent 6 out of 10 inhalers dispensed in BC.47

The leaf icon in Appendix C: Asthma Medication Table indicates lower environmental impact medication options. For detailed information about the impact of specific medications, please see the Inhaler Coverage and Environmental Impact Guide.

The leaf icon in Appendix C: Asthma Medication Table indicates lower environmental impact medication options. For detailed information about the impact of specific medications, please see the Inhaler Coverage and Environmental Impact Guide.Spacer Devices for MDIs

Spacer devices (valved holding chamber) must be bought separately; however, spacers make it easier for a patient to use their MDI and they distribute medication to the lungs more effectively. Spacer devices are recommended for all ages of patients prescribed a MDI, particularly with inhaled corticosteroids.

Dry Powder Inhaler (DPI)

Dry Powder Inhaler (DPI)

DPIs rely on the force a patient generates to inhale their medication rather than a propellant, which makes them a more environmentally friendly option. DPIs are contraindicated for young children or adult patients with comorbidities such as neuromuscular weakness or frailty.

Propellant-free devices may also have an impact in other environmental spheres.33 One of the reasons correct diagnosis is so important is to avoid prescribing needless medication including containers and chemicals.33

Nebulizers are no longer recommended for any age group. MDI with spacer is as effective as a nebulizer34 and spacer devices carry lower infection risk than nebulizers.

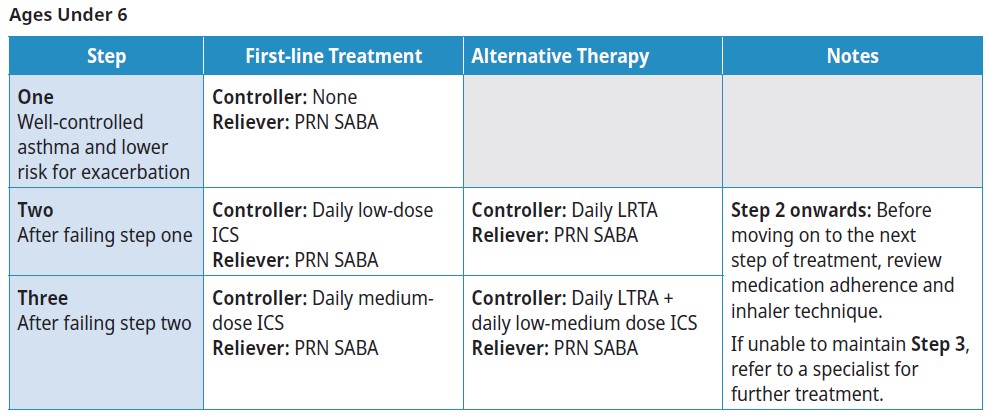

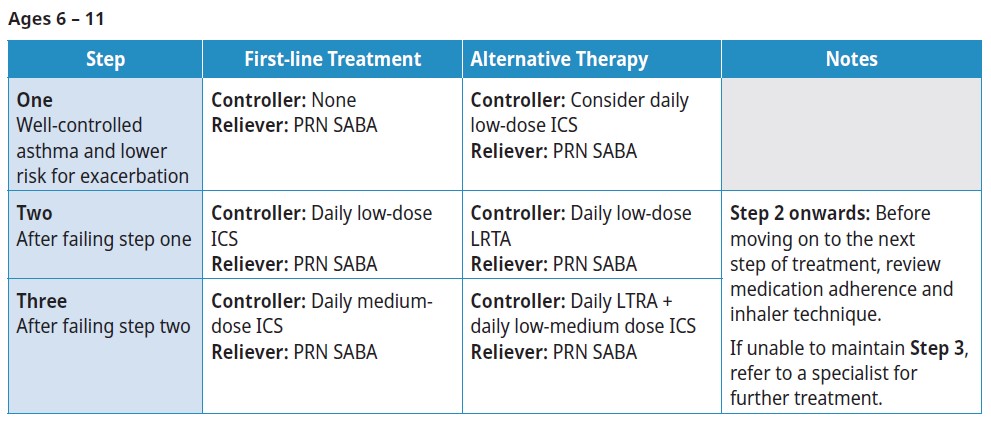

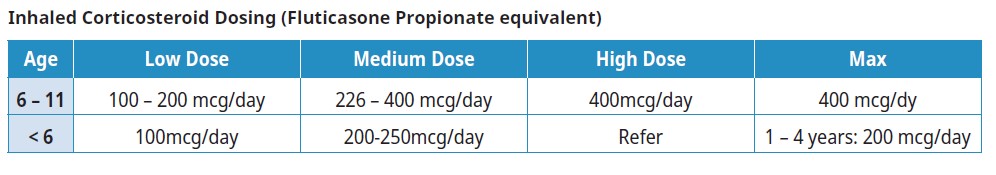

Stepwise Approach

Begin with the step most appropriate to the initial severity of the patient’s asthma. If symptom control is insufficient (see Table 6. Assessing asthma symptom control), the reasons for poor control should be assessed prior to or in conjunction with proceeding to the next step up. This includes assessment of:

- Adherence

- Inhalation technique (including whether they have been using an empty inhaler)

- Environmental exposures

- Comorbidities (e.g., rhinosinusitis, GERD, etc.) that may worsen or mimic asthma symptoms

If symptom control is maintained and exacerbation risks are well-managed over at least 3 months, consider stepping down to the previous step. Ensure the patient has had no exacerbations in the past year before stepping down treatment.

Asthma Management During Pregnancy

Pregnant patients should not stop their medication during pregnancy.

- Medication: Most asthma treatments are considered safe during pregnancy, but budesonide is considered the safest inhaled corticosteroid for pregnant patients.35 The risks of untreated asthma symptoms during pregnancy is much higher than with those associated with asthma medications.36

- Action plan: Part of a pregnant patient's action plan should include contacting their obstetrical care provider during exacerbations to monitor fetal well-being. Consider involving both an obstetrical care provider and an asthma specialist.

- Monthly asthma assessment: As many as 1/3 may experience worsening asthma symptoms during pregnancy and would benefit from closer (monthly) monitoring.37

Pregnant patients with uncontrolled or severe asthma should be managed by a specialist.

Biologics and Add-on Therapies

Biologics and Add-on Therapies

The biologics used in asthma are reserved for patients with severe asthma and should be prescribed by asthma specialists after:

- Confirming that a patient requires high dose inhaled steroids and

- A second controller medication to control their asthma (or remain uncontrolled despite those medications).38

For patients to be eligible for PharmaCare coverage of asthma biologics, good adherence to asthma controllers (as assessed by prescription refills in PharmaNet) is needed, so it is useful to ensure that patients are appropriately filling their controller prescription prior to referring them to a specialist.

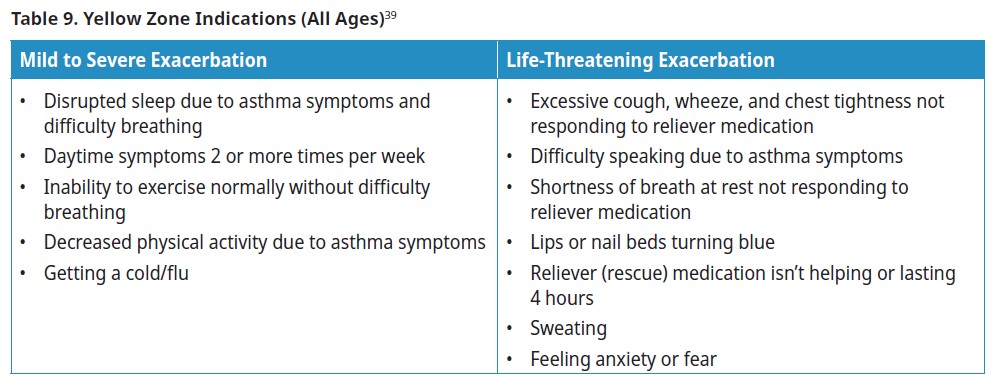

Navigating an Exacerbation - the Yellow Zone

Individuals having increased asthma symptoms are typically in the “yellow zone” of their asthma action plan. (See Associated Documents: Asthma Action Plans). The yellow zone can be taken as a symptom-based caution sign that a patient is at risk of experiencing an exacerbation and that their medicine needs to be increased.

Symptoms indicative of the yellow zone are in Table 9, below. Early recognition of the yellow zone and intervention are important to successfully stabilizing asthma.1

Patients who experience “Mild to Severe” symptoms are encouraged to follow their action plan and/or to book an urgent appointment with their health care provider. An exacerbation could be imminent, and early support could prevent it. Patients who are having symptoms of a life-threatening asthma exacerbation should seek immediate attention.

Yellow Zone Management

In children it is not recommended to increase the dose of inhaled corticosteroids in the yellow zone as this can lead to increased side-effects and hasn’t been shown to be effective.7

In children it is not recommended to increase the dose of inhaled corticosteroids in the yellow zone as this can lead to increased side-effects and hasn’t been shown to be effective.7

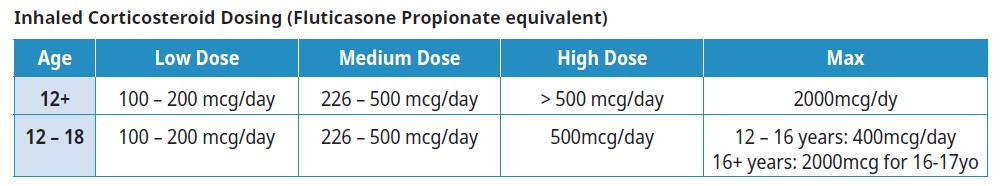

In adults who have had an exacerbation in the last year, a trial of a 4- or 5-fold increase in maintenance ICS dose for 7-14 days is suggested.7 Please note: this dose exceeds product monograph total daily dose limits and is not intended for chronic daily use. A short-term dose increase beyond these limits is unlikely to carry any significant safety risks, however formal safety testing data are not available and the decision to pursue this approach should be based on patient and clinician comfort. Prescribers should be aware of the maximum doses of ICS and LABA approved for use in Canada (see Appendix C: Asthma Medication Table).

In adults who have had an exacerbation in the last year, a trial of a 4- or 5-fold increase in maintenance ICS dose for 7-14 days is suggested.7 Please note: this dose exceeds product monograph total daily dose limits and is not intended for chronic daily use. A short-term dose increase beyond these limits is unlikely to carry any significant safety risks, however formal safety testing data are not available and the decision to pursue this approach should be based on patient and clinician comfort. Prescribers should be aware of the maximum doses of ICS and LABA approved for use in Canada (see Appendix C: Asthma Medication Table).

There are significant adverse events associated with as few as 4 short courses of systemic steroids in a lifetime. Requiring a course of systemic steroids should trigger a thorough assessment of a patient’s asthma.46

Ongoing Care

Review the following with the patient at regular office visits:*

- Medication adherence

- Inhaler technique (e.g., have patient demonstrate how they take their inhalers)

- How to monitor symptoms

- Level of symptom control and ability to follow lifestyle modifications

- Asthma action plan (modify if necessary)

After a Severe Exacerbation

Schedule follow-up visits within 2-4 weeks of any severe exacerbation that required an ER visit, hospitalization, or systemic steroid use. At this visit, assess:

- Modifiable risk factors for the exacerbation (e.g., medication adherence, inhaler technique)

- Whether they used their action plan correctly

- Whether changes need to be made to their action plan

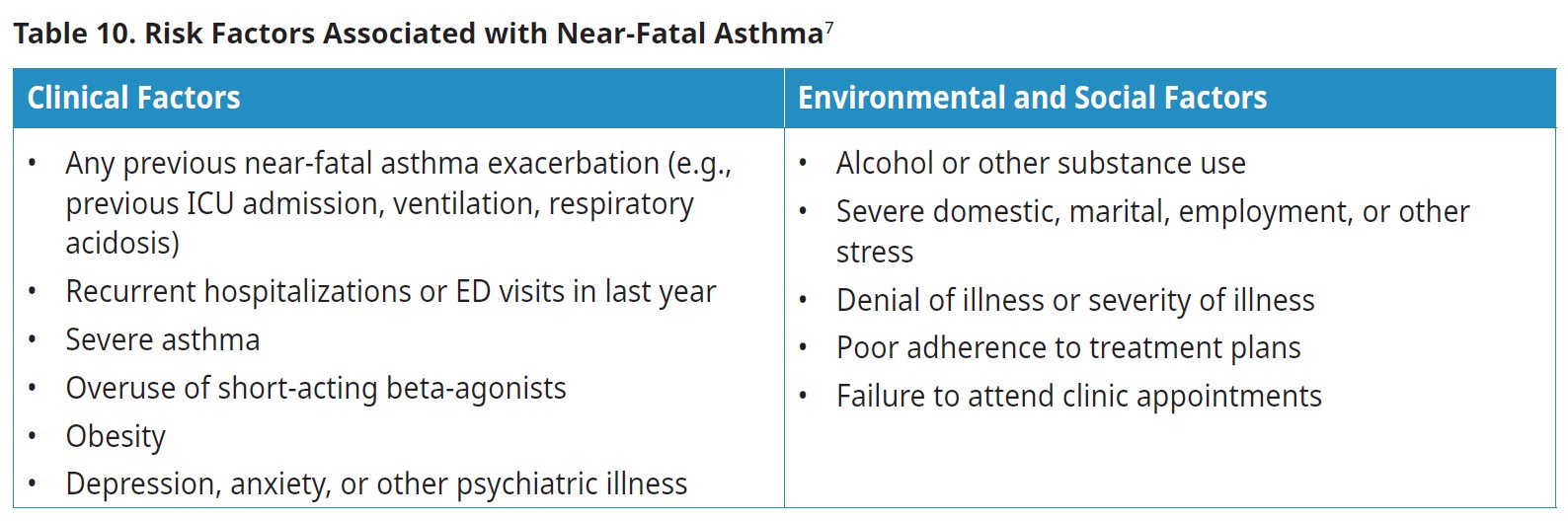

Patients with risk factors associated with near-fatal asthma attacks (see Table 10. Risk factors associated with near-fatal asthma, below) require careful follow-up. See the Resources section of this guideline.

Reassessing Persistence of Asthma Symptoms in Children <6yrs

Reassessing Persistence of Asthma Symptoms in Children <6yrs

50% of preschool age children with wheezing outgrow their asthma by age 6.40 Therefore, the need for ongoing therapy in children < 6 should be re-evaluated every 6-12 months.

A trial off controller medication may be considered for children who have been well-controlled (with no exacerbations) during exposure to their typical triggers for the past 6 to 12 months.7 Monitor closely during the trial period.

Influenza and COVID-19

Influenza and COVID-19 can contribute to acute asthma exacerbations.9 Vaccination reduces the risk of infection. Encourage patients to maintain their regular influenza and COVID-19 vaccinations.

Mask wearing can reduce the spread of viral illness and is not a risk factor for exacerbations.41

Indications for Referral

- Atypical asthma symptoms or diagnostic uncertainty

- Poorly controlled asthma or asthma exacerbations despite asthma control (poor lung function, persistent asthma symptoms) despite good adherence to step 3 or 4 treatment (see Stepwise approach)

- Frequent asthma exacerbations despite moderate doses of inhaled corticosteroids (with proper technique and good adherence)

- Need for allergy testing to assess the possible role of environmental allergens in those with a suggestive clinical history

- Occupational asthma may be indicated

- Patient is pregnant and has severe asthma

- Any asthma hospitalization, ³ 2 ED visits, or ³ 2 courses of systemic steroids

- A life-threatening event such as ICU admission for asthma

Environmental Impact and Climate Change

Climate and Asthma Management

While asthma exacerbations can occur at any time during the year, there are seasonal patterns.42

In children, exacerbation rates are highest in the fall. The “September Epidemic” has been attributed to an increased in rhinovirus respiratory infections among children when they return to school. Environmental factors (pollen, temperature, and air pollutants) also contribute to this phenomenon.

Climate change impacts the seasonal asthma cycle in two ways

- By shifting weather patterns, which can lead to a prolonged pollen season43

- Through increasingly common climate events, such as wildfires22

Other climate events, such as heat domes44 and flooding43 may also present exacerbation risks for patients with asthma. Consider climate events when developing their Asthma Action Plans.

Controversies of Care

Use of Short-acting Beta-agonists Alone as a Treatment Option in Very Mild Asthma

Use of Short-acting Beta-agonists Alone as a Treatment Option in Very Mild Asthma

Some guidelines recommend that no patient with asthma should be prescribed a SABA alone given the evidence for decreasing exacerbations in patients with mild to severe asthma. Others leave PRN SABA as an option for those with very mild asthma (see Asthma severity) who are at lower risk for exacerbations (see Assessing control and risk).

Preference for Daily Inhaled Corticosteroids for those with Mild Asthma

Preference for Daily Inhaled Corticosteroids for those with Mild Asthma

Some guidelines advise adults with mild asthma be prescribed PRN ICS-formoterol regimens as patients generally do not adhere to daily medication. Others recommend daily ICS as first-line (as this leads to better asthma control and improved lung function) and PRN ICS-formoterol regimens only as first-line treatment in patients ages 12+ with poor adherence to daily medication despite adequate asthma education and support.

Physical Activity, Healthy Diet, and Breathing Exercises

Evidence that physical activity, healthy diet, and breathing exercises mitigate asthma is inconclusive, but the evidence that these practices improve quality of life is fair.9

Wait Times and Accessibility

Wait times and location for spirometry vary across the province. In some regions, the distance to a facility may be prohibitive, or the amount of time between referral and procedure may fall outside the recommended testing interval.

Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS)

Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS) was mentioned in previous guidelines. While asthma and COPD do share similarities, ACOS has not been clearly defined.45

Practitioners are discouraged from diagnosing patients with ACOS.

Resources

References

1 Lougheed MD, Lemiere C, Ducharme FM, Canadian Thoracic Society Asthma Clinical Assembly, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society 2012 guideline update: diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers, children and adults. Can Respir J. 2012;19(2):127–164. doi:10.1155/2012/635624.

2 Chen W, Tavakoli H, FitzGerald JM, Subbarao P, Turvey SE, Sadatsafavi M. Age trends in direct medical costs of pediatric asthma: A population study. Kalaycı Ö, editor. Pediatric Allergy Immunology. 2021 Aug;32(6):1374–7.

3 (2012), Cost Risk Analysis for Chronic Lung Disease in Canada.

4 Canadian Institute for Health Information: Asthma Emergency Department Visits: Volume and Median Length of Stay, 2014-2015, http://indicatorlibrary.cihi.ca/

5 Canadian Institute for Health Information. Asthma Hospitalizations Among Children and Youth in Canada:Trends and Inequalities. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2018.

6 American Lung Association. What Causes Asthma? [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 11]. Available from: https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease- lookup/asthma/learn-about-asthma/what-causes-asthma

7 Connie L. Yang, Elizabeth Anne Hicks, Patrick Mitchell, Joe Reisman, Delanya Podgers, Kathleen M. Hayward, Mark Waite & Clare D. Ramsey (2021): Canadian Thoracic Society 2021 Guideline update: Diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers, children and adults, Canadian Journal of Respiratory, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, DOI: 10.1080/24745332.2021.1945887

8 British Thoracic Society Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. Thorax. 2008 May 1;63(Supplement 4):iv1–121.

9 Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (2022 Update) [Internet]. 2022 p. 225. Available from: https://ginasthma. org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GINA-Main-Report-2022-FINAL-22-07-01-WMS.pdf

10 Coates AL, Graham BL, McFadden RG, McParland C, Moosa D, Provencher S, et al. Spirometry in Primary Care. Canadian Respiratory Journal. 2013;20(1):13–22.

11 Ng B, Sadatsafavi M, Safari A, FitzGerald JM, Johnson KM. Direct costs of overdiagnosed asthma: a longitudinal, population-based cohort study in British Columbia, Canada. BMJ Open. 2019 Nov;9(11):e031306.

12 Langan RC, Goodbred AJ. Office Spirometry: Indications and Interpretation. Am Fam Physician. 2020 Mar 15;101(6):362–8.

13 B 2020 Focused Updates to the Asthma Management Guidelines [Internet]. NHLBI; 2020 Dec [cited 2022 Dec 12] p. 322. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/ resources/2020-focused-updates-asthma-management-guidelines

14 Yang CL. Age for allergy testing. 2022.

15 Shaw D, Green R, Berry M et al. A cross-sectional study of patterns of airway dysfunction, symptoms and morbidity in primary care asthma. Prim Care Respir J 2012; 21(3):283-7.

16 Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:948-968.

17 Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Boulet LP, et al. Overdiagnosis of asthma in obese and nonobese adults. CMAJ 2008; 179(11):1121-31.

18 Johnson J, Abraham T, Sandhu M, Jhaveri D, Hostoffer R, Sher T. Differential Diagnosis of Asthma. In: Allergy and Asthma [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019 [cited 2023 Jan 5]. p. 383–400. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-05147-1_17

19 British guideline on the management of asthma: a national clinical guideline. Revised edition. Edinburgh: Healthcare Improvement Scotland; 2019.

20 Government of Canada. Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS): summary of results for 2019 [Internet]. 2020 Jul. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/ en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-nicotine-survey/2019-summary.html

21 Asthma [Internet]. WorkSafe BC; [cited 2022 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.worksafebc.com/en/health-safety/injuries-diseases/asthma

22 Government of BC. Wildfire Season Summary [Internet]. 2022 Mar. Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/safety/wildfire-status/about-bcws/wildfire- history/wildfire-season-summary

23 Henderson SB, Brauer M, MacNab YC, Kennedy SM. Three Measures of Forest Fire Smoke Exposure and Their Associations with Respiratory and Cardiovascular Health Outcomes in a Population-Based Cohort. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011 Sep;119(9):1266–71.

24 Yao J, Eyamie J, Henderson SB. Evaluation of a spatially resolved forest fire smoke model for population-based epidemiologic exposure assessment. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2016 May;26(3):233–40.

25 Rappold AG, Stone SL, Cascio WE, Neas LM, Kilaru VJ, Carraway MS, et al. Peat Bog Wildfire Smoke Exposure in Rural North Carolina Is Associated with Cardiopulmonary Emergency Department Visits Assessed through Syndromic Surveillance. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011 Oct;119(10):1415–20.

26 Delfino RJ, Brummel S, Wu J, Stern H, Ostro B, Lipsett M, et al. The relationship of respiratory and cardiovascular hospital admissions to the southern California wildfires of 2003. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2009 Mar 1;66(3):189–97.

27 Martin KL, Hanigan IC, Morgan GG, Henderson SB, Johnston FH. Air pollution from bushfires and their association with hospital admissions in Sydney, Newcastle and Wollongong, Australia 1994-2007. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2013 Jun;37(3):238–43.

28 Reid CE, Brauer M, Johnston FH, Jerrett M, Balmes JR, Elliott CT. Critical Review of Health Impacts of Wildfire Smoke Exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Sep;124(9):1334–43.

29 Hauptman M, Anderko L, Sacks J, Strine L, Damon S, Stone S, et al. Wildfire Smoke Factsheet: Protecting Children from Wildfire Smoke and Ash [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.airnow.gov/sites/default/files/2021-06/pehsu-protecting-children-from-wildfire-smoke-and-ash-factsheet.pdf

30Gear up for wildfire season [Internet]. BC CDC; 2022 Jul [cited 2022 Oct 7]. Available from: http://www.bccdc.ca/about/news-stories/stories/2022/gear-up-for- wildfire-season

31 Forest Fires and Lung Health [Internet]. Canadian Lung Association; Available from: https://www.lung.ca/lung-health/forest-fires-and-lung-health

32 Kevin E. Liang, MD, CCFP, Jiayun Angela Yao, PhD, Philip Hui, MD, FRCPC, Darryl Quantz, MFPH, MPH, MSc. Climate impact of inhaler therapy in the Fraser Health region, 2016–2021. BCMJ, Vol. 65, No. 4, May, 2023, Page(s) - Clinical Articles.

33 Jeswani HK, Azapagic A. Life cycle environmental impacts of inhalers. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2019 Nov;237:117733.

34 Fayaz M, Sultan A, Rai ME. Comparison between efficacy of MDI+spacer and nebuliser in the management of acute asthma in children. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2009;21(1):32–4.

35 Asthma Attacks. Asthma Canada [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 22]; Available from: https://asthma.ca/get-help/living-with-asthma/asthma-attacks/

36 Silverman M, et al. (2005). Outcome of pregnancy in a randomized controlled study of patients with asthma exposed to budesonide. Annals of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, 95(6): 566–570.

37 Asthma During Pregnancy [Internet]. Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America; [cited 2023 Jan 3]. Available from: https://aafa.org/asthma/living-with-asthma/ asthma-during-pregnancy/

38 Biologic Treatment for Severe Asthma. Asthma Canada [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 20]; Available from: https://asthma.ca/get-help/severe-asthma/biologics/

39 National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (2005). Working Group Report on Managing Asthma During Pregnancy: Recommendations for Pharmacologic Treatment Update 2004 (NIH Publication No. 05-5236). Available online: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/prof/lung/asthma/astpreg.htm

40 Morgan WJ, Stern DA, Sherrill DL, et al. Outcome of asthma and wheezing in the first 6 years of life: follow-up through adolescence. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1253-1258.

41 Face Masks and Other Prevention Strategies [Internet]. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2022. Available from: https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel- coronavirus-covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/face-masks-and-other-prevention-strategies/

42 Teach SJ, Gergen PJ, Szefler SJ, Mitchell HE, Calatroni A, Wildfire J, et al. Seasonal risk factors for asthma exacerbations among inner-city children. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2015 Jun;135(6):1465-1473.e5.

43 D’Amato G, Chong‐Neto HJ, Monge Ortega OP, Vitale C, Ansotegui I, Rosario N, et al. The effects of climate change on respiratory allergy and asthma induced by pollen and mold allergens. Allergy. 2020 Sep;75(9):2219–28.

44 Extreme Heat and Human Mortality: A Review of Heat-Related Deaths in BC in Summer 2021 [Internet]. BC Coroners Service; 2022 Jun [cited 2022 Jul 11] p. 56. Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/death-review-panel/extreme_heat_death_ review_panel_report.pdf

45 Mekov E, Nuñez A, Sin DD, Ichinose M, Rhee CK, Maselli DJ, et al. Update on Asthma–COPD Overlap (ACO): A Narrative Review. COPD. 2021 Jun;Volume 16:1783–99.

46 Price D, Castro M, Bourdin A, Fucile S, Altman P. Short-course systemic corticosteroids in asthma: striking the balance between efficacy and safety. Eur Respir Rev. 2020 Mar 31;29(155):190151.

47 Valeria Stoynova. Provincial-level carbon footprint data. 2023.

Abbreviations:

FABA Fast-acting beta agonist

LABA Long-acting beta agonist

SABA Short-acting beta agonist

Bud/form A single inhaler containing both budesonide and formoterol

PRN “Pro re neta”, or “as needed”

ICS Inhaled corticosteroid

HFA Hydrofluoroalkane

LTRA Leukotriene receptor antagonist

MDI Metered dose inhaler

DPI Dry powder inhaler

Practitioner Resources

- RACE Line: Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise Program: a phone app for physicians, nurse practitioners and medical residents. raceconnect.ca/

- PathwaysBC: An online resource that allows GPs and nurse practitioners and their office staff to quickly access current and accurate referral information, including wait times and areas of expertise, for specialists and specialty clinics. See: https://pathwaysbc.ca/login

- Health Data Coalition: An online, physician-led data sharing platform that can assist you in assessing your own practice in areas such as chronic disease management or medication prescribing. See: Health Data Coalition – Better Information. Better Care. Better Patient Outcomes. (hdcbc.ca)

- General Practice Services Committee: Home page | GPSC (gpscbc.ca)

- Practice Support Program: offers focused, accredited training sessions for BC physicians to help them improve practice efficiency and support enhanced patient care.

- Chronic Disease Management and Complex Care Incentives: compensates GPs for the time and skill needed to work with patients with complex conditions or specific chronic diseases.

- British Columbia Centre of Disease Control: bccdc.ca/

- BC Children’s Hospital: bcchildrens.ca/

- Work Safe BC: worksafebc.com/en

- Creating A Sustainable Canadian Health System In A Climate Crisis (CASCADES):

Emergency Management and Planning:

- Gov.bc.ca: Emergency Management

- Building Resilient Rural Communities: Responding to Climate Change & Ecosystem Disruption

Patient, Family and Caregiver Resources

- Health Link BC: You may call HealthLinkBC at 8-1-1 toll-free in B.C., or for the deaf and the hard of hearing, call 7-1-1. You will be connected with an English-speaking health-service navigator, who can provide health and health-service information and connect you with a registered dietitian, exercise physiologist, nurse, or pharmacist. See: healthlinkbc.ca/

- Doctors of BC: doctorsofbc.ca/: Stay Active, Stay Safe

- BC Children’s Asthma Resources for Families: bcchildrens.ca

-

PHSA Asthma Education Videos

-

Creating A Sustainable Canadian Health System In A Climate Crisis (CASCADES):

Air Quality and Wildfire Resources

- Gov.bc.ca:

- BC CDC:

- Wildfire Smoke Response Planning (bccdc.ca)

- British Columbia Asthma Prediction System (BCAPS): https://maps.bccdc.ca/bcaps/

- Videos:

- Quit Smoking: It provides one-on-one support and valuable resources in multiple languages to help you plan your strategy and connect with a Quit Coach. See: Community and Support | QuitNow. Phone: 1-877-455-2233 (toll-free) Email: quitnow@bc.lung.ca

- Smokers’ Helpline at 1-866-366-3667 or visit Home (smokershelpline.ca)

Diagnostic code: 493 (Asthma)

Appendices

- Appendix A: Getting Ready for Spirometry (PDF, 100KB)

- Appendix B: Supporting Patients with Poor Medication Adherence (PDF, 97KB)

- Appendix C: Asthma Medication Table (PDF, 135KB)

Associated Documents

The following documents accompany this guideline:

- Asthma Action Plans and Translations

- Asthma Patient Care Flow Sheet for Adults (PDF, 57KB)

- Asthma Patient Care Flow Sheet: aged < 6 years (PDF, 64KB)

- Asthma Patient Care Flow Sheet: aged 6-18 years (PDF, 63KB)

List of Contributors

List of Contributors (PDF, 33KB)

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the Effective Date.

This guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, approved by the British Columbia Medical Association, and adopted by the Medical Services Commission.

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

Contact InformationGuidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee E-mail: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca Web site: www.BCGuidelines.ca |

Disclaimer

The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the “Guidelines”) have been developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The Guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The Guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional.