Tobacco Use Disorder (TUD)

Effective Date: October 24, 2024

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Background

- Epidemology

- Screening and Brief Intervention

- Pharmacological Management of TUD

- Special Populations

- Vaping Use

- Controversies in Care

- Appendices

- References

Scope

This guideline provides evidence-based recommendations for primary care practitioners on managing tobacco use disorder (TUD). The term ‘tobacco’ refers to commercial, smoked and smokeless tobacco (e.g., chew and snuff). This guideline also addresses vaping. While the guideline focuses on TUD in adults (ages ≥ 19), there are some recommendations addressing the youth population (ages 12-18).

Indigenous populations: Cultural safety and humility are important when offering care. The First Nations Health Authority has stated, “For thousands of years, natural tobacco has been an integral part of Indigenous culture in many parts of British Columbia and Canada. Used in ritual, ceremony and prayer, tobacco was considered a sacred plant with immense healing and spiritual benefits. For these reasons, the tobacco plant should be treated with great respect. [Be] careful not to confuse traditional tobacco and its sacred uses with commercial tobacco.”1,2

Key Recommendations

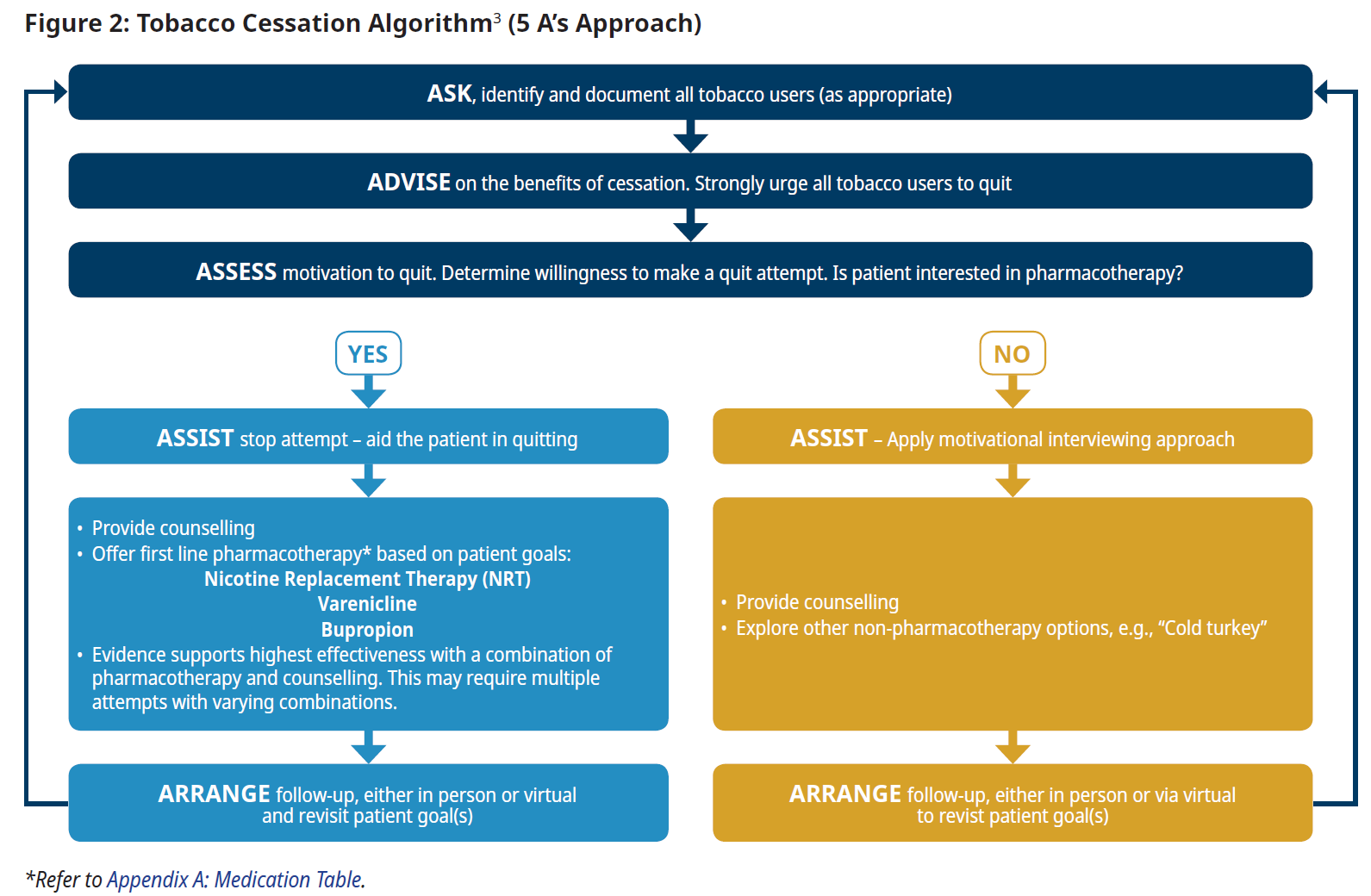

- Tobacco use disorder (TUD) (defined in the DSM-5-TR), like other substance use disorders, is a chronic and often relapsing condition. Document smoking history by number of years spent smoking (now considered a better risk indicator than “pack years”). Ask regularly about smoking status and document tobacco use in the patient medical record, including number of cessation attempts. Use the Tobacco Cessation Algorithm (5 A’s Approach) see Figure 2. 3–9

- Acknowledge that relapse is common and can be expected. If a patient has resumed tobacco use, offer education and review and adjust their smoking cessation plan.3,4,7,9,10

- Continue to provide brief interventions (BI), which are effective when routinely repeated.3,4,7,10,11 Consider a motivational interviewing (MI) approach with all patients, including those not yet ready to stop smoking. See Practitioner Resources section for detailed MI information.3,8,9

- The most effective way to stop smoking is a combination of both pharmacotherapy and counselling.4–6,9–14 Treatment plans should be individually and collaboratively tailored.

- Medications: Encourage first-line pharmacotherapy, including nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), varenicline, and bupropion. See Appendix A: Tobacco Use Disorder Medication Table.

- Counselling: Smoking cessation programs provide support to those who plan to quit smoking. Encourage patients to connect with QuitNow or to the FNHA’s Talk Tobacco Program.

- Ask regularly about and document vaping use (including youth). Advise and support efforts to quit vaping.

Background

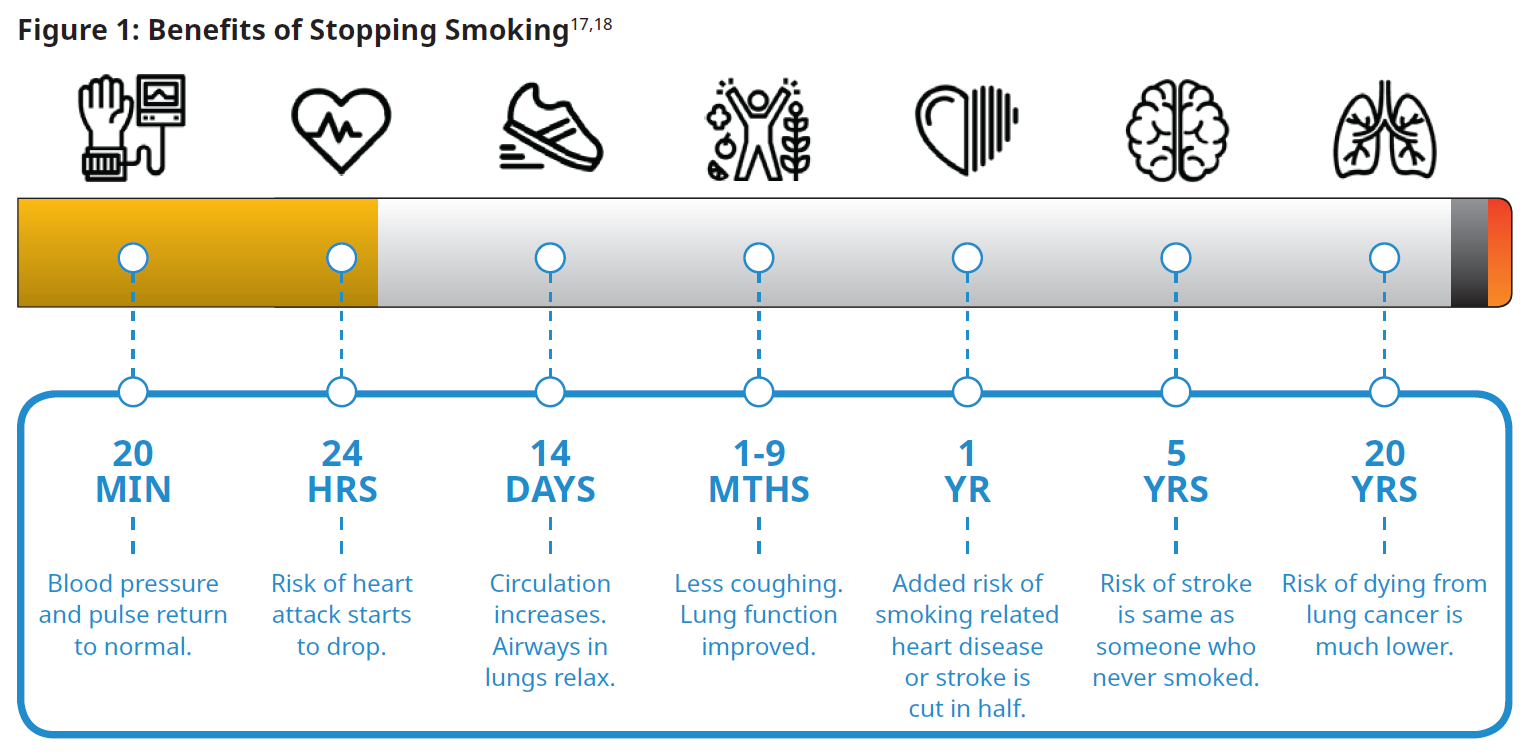

Tobacco use disorder (TUD), like other substance use disorders, is a chronic and often relapsing condition. Smoking cessation is associated with a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality rates. Timelines for specific benefits are outlined in the diagram below, Figure 1: Benefits of Stopping Smoking. Compared to patients who continue to smoke, people who have stopped smoking experience reductions in anxiety, depression, and stress symptoms as well as improvements in positive feelings and mental wellness.15,16

Previously, pack years were used to help stratify health risks. Rather than pack years, the number of years spent smoking is now considered to be a better risk indicator.

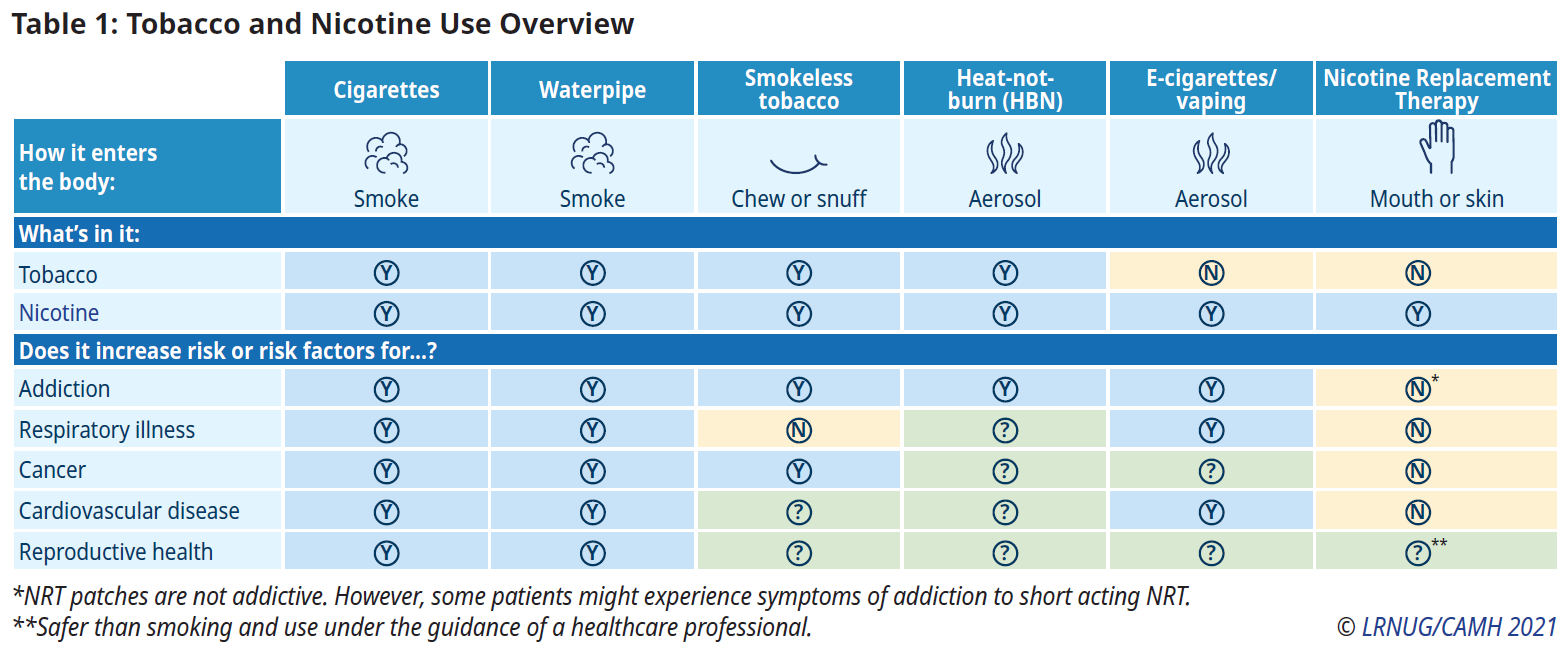

Different forms of tobacco use present different harms. Table 1: Tobacco and Nicotine Use Overview (below) details these differences

Radon exposure acts synergistically with smoking to increase lung cancer risk. Concerning levels of radon are present in many BC communities (refer to the BCCDC webpage).

Epidemiology

The 2022 Canadian Nicotine and Tobacco Survey (CNTS) found that 5.3% of BC youth and 8.5% of BC adults smoked.19

Tobacco smoking is the leading cause of preventable death in British Columbia, accounting for approximately 6,000 deaths annually. In BC, more deaths are due to smoking than to the combination of deaths due to all other drugs, motor vehicle collisions, murder, suicide, and HIV/AIDS.20, 21, 22 Individuals who smoke die on average 10 years prematurely, and those who start smoking younger, are at increased risk of premature death.23-25

The main causes of smoking-related deaths are cancers (e.g., lung, oral, esophageal, laryngeal), cardiovascular disease, and respiratory diseases. Other cancers, such as liver, pancreatic, and cervical, can be caused by smoking.26

Screening and Brief Intervention

TUD can be quickly and easily identified. Ask regularly about smoking status and document tobacco use in the patient medical record, including number of cessation attempts. Use the 5 A’s approach to discuss readiness to stop.3–9 Further details can be found in the World Health Organization’s Toolkit for delivering the 5A’s and 5R’s brief tobacco interventions in primary care. Smoking cessation programs provide support to those who plan to quit smoking. Encourage patients to connect with QuitNow or to the FNHA’s Talk Tobacco Program.

Acknowledge that relapse is common. If a patient has resumed tobacco use, offer education and review and adjust their smoking cessation plan.3,4,7,9,10 Continue to provide brief interventions (BI), which are effective when routinely repeated.3,4,7,9–11 Treatment plans should be individually and collaboratively tailored.

Other healthcare professionals, e.g., nurses, and respiratory therapists, can also support smoking cessation efforts.

Pharmacological Management of TUD

The approved smoking cessation medications available in Canada are nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), varenicline and bupropion. These medications reduce nicotine withdrawal symptoms and cravings. Pharmacological approaches are most effective when used in combination with supportive counselling.27 The most effective interventions are varenicline and combination NRT followed by monotherapy NRT and bupropion.28

The choice of therapy should take into account the efficacy of treatment, the convenience of the dosing regimen and the side effect profile that match the patient’s values and preferences.11 Relapse following tobacco reduction or cessation is common. If a patient relapses, validate their experience and review their smoking cessation plan to see if there are adjustments that may improve success. This may require multiple attempts with varying combinations of pharmacotherapy and counselling.

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT)

NRT (i.e., patch, gum or lozenge) is used to reduce cravings, as it delivers nicotine that would otherwise have been obtained through tobacco use.10

Initial NRT dosing is typically based on the number of cigarettes smoked daily. For those who smoke heavily, more than one patch can be used simultaneously. NRT is recommended for a minimum of eight weeks. Some patients may find benefit in using NRT ≥ 12 weeks.10 Durations >12 weeks are not covered by PharmaCare. To prevent relapse, patients should be instructed to taper off NRT by no more than 7mg per week. This helps them adjust to lowering nicotine levels. In the case a patch dose decrease is linked with a burdensome increase in tobacco craving, that dose can be maintained for three to four weeks before an additional decrease is attempted.27

Types of NRT can be combined. A nicotine patch in conjunction with a faster-acting NRT (e.g., gum, lozenge) improved six- to 12-month abstinence rates by 5%.11 PharmaCare coverage for this approach is limited.

Success rates are higher in patients who cease tobacco use abruptly.10,11,29 For patients who do not wish to completely quit smoking, NRT may help reduce the amount smoked. Patients who continue smoking while using NRT will not experience significant side-effects, as they generally cut down their cigarette consumption to maintain similar daily nicotine intake.30 For patients not intending to stop smoking, NRT can relieve tobacco withdrawal symptoms in settings where smoking is prohibited e.g., hospitals, airplanes, smoke-free workplaces. It is safe for patients with stable cardiovascular disease to use NRT. Exercise caution in patients with unstable cardiovascular disease (e.g. angina, arrhythmias or recent myocardial infarction within 2 weeks).11, 31, 32

Varenicline

Varenicline should be started at least one week prior to the patient’s quit date and continued for 12 consecutive weeks.33 Based upon patient and practitioner discussion, it is safe to consider a further 12 week course to reduce relapse.11,34 PharmaCare only covers one course of 12 consecutive weeks per year.

Bupropion

Bupropion is less effective than varenicline or combined NRT.28 Combining bupropion and NRT does not appear to increase a patient’s likelihood of quitting.35 If used, bupropion should be started at least one week prior to the patient’s quit date and continued for at least seven weeks.10,11

Other Pharmacological Considerations

Encourage patients not to abandon pharmacotherapy for manageable side effects e.g., nausea and insomnia.

Pharmacotherapy options may be used for longer periods of time than recommended in product monographs. However, pharmacotherapy is not as effective if used for shorter durations than product monograph recommendations.36, 37

Stopping smoking can affect the metabolism of other drugs, potentially requiring dosage adjustments. Refer to the Drug InterACTIONs with Tobacco Smoke.

Special Populations

Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders

Patients with mental health disorders and/or with substance use disorders may begin and continue to use tobacco for a variety of reasons, including self-medication and social circumstances.38 There are higher smoking rates among these populations, and higher levels of encouragement and support may be beneficial.

The NRT patch, varenicline, and bupropion are effective and well tolerated in adults with psychotic, anxiety, and mood disorders.13,27

Marginalized Groups

Certain populations have a higher incidence of smoking and more barriers to quitting. Consider socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, social marginalization, stress, and lack of community empowerment.37

Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

For detailed information on supporting these patients, see QuitNow BC’s Pregnancy and Smoking page, Perinatal Services BC’s Tobacco and Nicotine Use During the Perinatal Period A Practice Resource for Health Care Providers, or Better Health’s Pregnancy and Smoking page. While behavioral interventions are the first line treatment option in this population, a risk benefit assessment may indicate a need for pharmacotherapy, in which NRT appears to be the safest choice.11

Youth (ages 12-18)

While behavioral interventions are the first line treatment option in this population, a risk benefit assessment may indicate a need for pharmacotherapy, of which NRT is the recommended option.39, 40 For youth smoking cessation strategies, refer to the CPS Practice Point: Strategies to promote smoking cessation among adolescents or the American Academy of Pediatrics: Nicotine Replacement Therapy and Adolescent Patients.

Children (ages <12)

Identify tobacco and vape usage. Refer to appropriate specialist care.

Vaping Use

Background and Epidemiology

Vaping entails inhaling an aerosol or vapour that is created by an electronic cigarette, vape pen, or personal vaporizer (i.e., “mods”). In BC, all legally sold vapes contain nicotine or cannabis (i.e., vapes cannot solely contain flavoured chemicals). Nicotine for vaping can be derived from tobacco leaves or produced synthetically.41

Aerosols from vapes contain harmful chemicals (e.g., acrolein and formaldehyde), particulate matter, and metals (e.g., aluminium, lead, tin and nickel).

While the incidence of initiation of tobacco smoking has decreased, there has been an increase in vaping use. The 2022 Canadian Nicotine and Tobacco Survey (CNTS) showed that 16.1% of BC youth ages 15-19 and 7% of adults ages 20+ had vaped in a preceding 30 day period.19 In 2023, of the BC youth who vaped, 15% vaped daily and 75% vaped within 30 minutes of waking up, suggesting physical dependence.41

Vaping does not reduce the risk of nicotine dependence. One vape pod can contain as much nicotine as one to two pack(s) of cigarettes.42, 43

People who have never smoked should not start vaping. Many people erroneously believe vaping is harmless. Many teens mistakenly believe there is no or slight risk in the occasional use of vapes.44

Youth who vape are more likely to transition to smoking.45 Children and youth become nicotine dependent at lower levels of nicotine exposure than adults.46 The developing brains of youth may also be more sensitive to the harmful effects of nicotine.34, 44

Due to an overall reduction in smoking, the tobacco industry has continued to expand its product portfolio to noncombustible products e.g., vaping and nicotine pouches (held in the mouth). Marketed as public health solutions, such products are aggressively promoted to youth and young adults.44, 47, 48 The fruity, menthol or mint flavoured vape cartridges may attract non-smoking youth, ultimately resulting in nicotine dependency.49

Screening and Brief Intervention

All patients, including children and youth, should be asked if they vape, and advised to quit. Practitioner assessments may include questions about dual use (i.e., vaping and smoking), physical and mental health, and social factors (e.g., stressors, partner vaping). There are currently no validated tools to assess vaping dependence.50

Treatment Approaches

The evidence on vaping and vaping cessation practices continue to emerge; practitioners should re-evaluate treatment plans over time.50

To support vaping cessation in adult patients, behavioural therapy strategies (e.g., counselling, motivational interviewing, cognitive-behavioural therapy) are first line treatment. In terms of pharmacotherapy, expert opinion from this working group suggests using short-term NRT for vaping cessation. The role of varenicline and bupropion is still emerging. Refer to the Pharmacological Management of TUD section above for additional information.

To support vaping cessation in youth, review CAMH's Vaping Cessation Guidance Resource. 50

Dual Use (individuals who both smoke and vape)

For patients who are both vaping and smoking, it is recommended to quit both concurrently. If unable, it is suggested that they switch to vaping only. Proceed with cessation management.51-53

Controversies in Care

Alternative Therapies for Smoking Cessation

While there is emerging evidence supporting cytisine use, dosing regimens are complex.28,54, 55 There is insufficient evidence to support heated tobacco products (HTPs),56-58 acupuncture, acupressure, laser therapy,59 and hypnotherapy.60 There is no evidence to support electrical stimulation,28 mindfulness,61 smoking cessation competitions,62 St. John’s wort (SJW),63 and S-Adenosyl-L-Methionine (SAMe).64

Resources

Abbreviations:

BI

HTP

MI

NRT

TUD

Brief intervention

Heated tobacco products

Motivational interviewing

Nicotine replacement therapy

Tobacco use disorder

Practitioner Resources

Tobacco Use Disorder Resources

- Quit Smoking: Offers health care providers training, education and resources to make it easier for you to support your clients on their quit journey. See: Health Care Providers | QuitNow. Phone: 1-877-455-2233 (toll-free) Email: quitnow@bc.lung.ca

- Pathways: Allows FPs and NPs and their office staff to quickly access current and accurate referral information. This includes wait times and areas of expertise for specialists and specialty clinics. Information on the BC Smoking Cessation Program can be found here: https://pathwaysbc.ca/programs/1026

- RACE Line: Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise Program: raceconnect.ca/. A phone consultation line for all physicians and NPs. If the relevant specialty area is available through your local RACE line, please contact them first. Please contact the Vancouver/Providence RACE line if your local RACE line does not cover the relevant specialty service or there is no local RACE line in your area.

- Family Practice Services Committee: Home page | GPSC (gpscbc.ca)

- Practice Support Program: offers focused, accredited and compensated support for FPs to help them improve practice efficiency and enhance patient care.

- Chronic Disease Management and Complex Care Incentives: compensates FPs working with patients with complex conditions or specific chronic diseases.

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH): A hub healthcare providers looking for more information and tools to support their clients who are seeking to stop smoking Resources for Providers.

- My Change Plan: The Workbook for Making Health Changes was developed by the Training Enhancement in Applied Counselling and Health (TEACH) Project as an interactive managed self-care tool that provides basic information on smoking cessation medications, the process of behaviour change and relapse prevention.

- Nicotine Dependence Clinic: Lower-Risk Nicotine Use Guidelines

- Vaping Cessation Guidance Resource: See screening tools and treatment approaches for vaping

- Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada: https://smoke-free.ca/

- Ottawa Model for Smoking Cessation: https://ottawamodel.ottawaheart.ca/

Continued Learning

- Motivational Interviewing:

- Nicotine Dependence Clinic - Mood Management:

- TEACH Certificate in Intensive Tobacco Cessation Counselling: The TEACH Project offers a University of Toronto accredited certificate program in intensive cessation counselling. This 46.5-hour certificate program provides the context, background and knowledge and skills needed to offer intensive tobacco cessation counselling.

- The Canadian Action Network for the Advancement, Dissemination and Adoption of Practice-informed Tobacco Treatment (CAN-ADAPTT): A practice-based research network facilitating research and knowledge exchange among providers, researchers and policy makers in the area of tobacco cessation. CAN-ADAPTT aim was to bridge the gap between research and practice.

Quality Improvement (QI)

- Smoking cessation intervention is well suited to QI efforts within a practice. Talk to a Physician Support Program (PSP) coaches can provide information on Continuing Medical Education (CME) credits and funding for QI projects: psp@doctorsofbc.ca

Possible Quality Indicators

- Tobacco use prevalence (includes smoking, vaping nicotine, and chew)

- all active patients ages ≥ 12 - Tobacco use prevalence - all active patients ages 12-19 inclusive

- Tobacco use documented in past 2 years – all active patients

Denominator for following: All active patients currently using tobacco

- % patients with tobacco cessation discussion documented

- % patients with dedicated tobacco use cessation consult and/or follow-up (behavioural, pharmacological, both)

Patient, Family and Caregiver Resources

BC Specific Resources

- HealthLinkBC: You may call 8-1-1 toll-free in B.C. For the deaf and the hard of hearing, call 7-1-1. You will be connected with an English-speaking health-service navigator, who can provide health and health-service information and connect you with a registered dietitian, exercise physiologist, nurse, or pharmacist. See: healthlinkbc.ca/

- BC Smoking Cessation Program – Patient Information Sheets (available in 10 languages)

- BC PharmaCare: Get help with tobacco cessation and learn what medications are available.

- QuitNowBC: BC’s free quit smoking service available to all BC Residents to reduce or quit. They offer synchronous online, phone and asynchronous coaching support.

- First Nations Virtual Doctor of the Day: The First Nations Virtual Doctor of the Day program enables First Nations people in BC with limited or no access to their own doctors to make virtual appointments. Call 1-855-344-3800 to book an appointment

- First Nations Health Authority (FNHA): Talk Tobacco offers culturally appropriate support about stopping smoking, vaping and commercial tobacco use to First Nations communities.

- Phone 1-833-998-8255, Text CHANGE to 123456, Live Chat on talktoblifetacco.ca Other resources developed by the FNHA:

- Respecting Tobacco

- Tobacco: The Sacred Medicine

- Coverage for Products to Quit the Use of Commercial Tobacco

- Frequently Asked Questions: Quitting Commercial Tobacco

National Resources

- Health Canada:

- Canadian Lung Association: Provides helpful suggestions for patients, see Cigarettes: the hard truth.

- Legacy for Airway Health: Addresses the health and economic burden of asthma and COPD through strategic research, proven prevention and delivery of optimal care.

- Expand Project: An initiative to start a dialog within queer and trans communities about smoking.

Youth-Specific Resources

- BC Ministry of Health: Health info for youth

- BC Ministry of Health: The A-Z of vaping

- BC Ministry of Health: Vaping brochure

- BC Lung Foundation: Vaping Frequently Asked Questions

- Canadian Lung Association: Vaping – what you need to know

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health: Vaping – what you and your friends need to know

- First Nations Health Authority: Youth Respecting Tobacco

- Health Canada: Risks of Vaping

- Health Canada: Talking with your teen about vaping

- McCreary Centre Society: What Parents Need to Know About Vaping - Parent Infographic

- Youth Research Academy: Clearing the Air - A youth-led research project about vaping

- Truth Initiative: Youth Vaping, Smoking and Nicotine Use

- Foundry: Myths and Facts on Vaping and Tobacco

Billing Codes

PG14066: Personal Health Risk Assessment (Prevention)

Appendices

Appendix A: Tobacco Use Disorder Medication Table

Associated Documents

The following documents accompany this guideline:

References

- First Nations Health Authority (FNHA). Respecting Tobacco [Internet]. First Nations Health Authority (FNHA); n.d. [cited 2023 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.fnha.ca/wellness/wellness-for-first-nations/wellness-streams/respecting-tobacco

- First Nations Health Authority (FNHA), Office of the Provincial Health Officer. First Nations Population Health and Wellness Agenda [Internet]. First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) and Office of the Provincial Health Officer; 2021 [cited 2022 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-PHO-First-Nations-Population-Health-and-Wellness-Agenda.pdf

- CAN-ADAPTT. Canadian Smoking Cessation Clinical Practice Guideline [Internet]. Canadian Action Network for the Advancement, Dissemination and Adoption of Practice-informed Tobacco Treatment, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2011 [cited 2022 Sep 10]. Available from: https://www.nicotinedependenceclinic.com/en/canadaptt/home

- Tobacco Use and Dependence Guideline Panel. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update [Internet]. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008 [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63952/

- Leone FT, Zhang Y, Evers-Casey S, Evins AE, Eakin MN, Fathi J, et al. Initiating Pharmacologic Treatment in Tobacco-Dependent Adults. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Jul 15;202(2):e5–31.

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Cabana M, et al. Interventions for Tobacco Smoking Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Persons: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021 Jan 19;325(3):265.

- McIvor A, Kayser J, Assaad JM, Brosky G, Demarest P, Desmarais P, et al. Best Practices for Smoking Cessation Interventions in Primary Care. Can Respir J. 2009;16(4):129–34.

- Manolios E, Sibeoni J, Teixeira M, Révah-Levy A, Verneuil L, Jovic L. When primary care providers and smokers meet: a systematic review and metasynthesis. Npj Prim Care Respir Med. 2021 Jun 1;31(1):31.

- Selby P, Zawertailo L. Tobacco Addiction. Solomon CG, editor. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jul 28;387(4):345–54. 10.

- Ministry of Health. The New Zealand guidelines for helping people to stop smoking: 2021 update [Internet]. Ministry of Health; 2021 [cited 2022 Sep 15]. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-zealand-guidelines-helping-people-stop-smokingupdate#:~:text=Give%20Brief%20advice%20to%20stop,everyone%20who%20accepts%20your%20offer.

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Supporting smoking cessation: A guide for health professionals. In 2021. Available from: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinicalguidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/supporting-smoking-cesstiona

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Tobacco: preventing uptake, promoting quitting and treating dependence [Internet]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2023 [cited 2022 Sep 15]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/ guidance/ng209

- Evins AE, Benowitz NL, West R, Russ C, McRae T, Lawrence D, et al. Neuropsychiatric Safety and Efficacy of Varenicline, Bupropion, and Nicotine Patch in Smokers With Psychotic, Anxiety, and Mood Disorders in the EAGLES Trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;39(2):108–16.

- Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T. Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network metaanalysis. Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2013 May 31 [cited 2023 Mar 13];2015(7). Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2

- Taylor GMJ, Treur JL. An application of the stress-diathesis model: A review about the association between smoking tobacco, smoking cessation, and mental health. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2023 Jan 1;23(1):100335.

- Taylor GM, Lindson N, Farley A, Leinberger-Jabari A, Sawyer K, Naudé R te W, et al. Smoking cessation for improving mental health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Apr 29];(3). Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/ doi/10.1002/14651858.CD013522.pub2/full

- QuitNow. Benefits of Quitting [Internet]. QuitNow; n.d. [cited 2022 Sep 10]. Available from: https://quitnow.ca/quitting/thinking-aboutquitting/benefits-quitting?gclid=CjwKCAiAl9efBhAkEiwA4Torig0y1f0fUpHbGSL7QJPzYONgk4DOdFumXlvPOKzXQbb6FD3ekbXimhoCjaQ QAvD_BwE

- The Wellness Institute. Don’t Smoke [Internet]. The Wellness Institute; n.d. [cited 2022 Oct 1]. Available from: https://wellnessinstitute.ca/smoking-cessation/

- Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS): summary of results for 2022 [Internet]. Canada.ca. 2023. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-nicotine-survey/2022-summary.html48.

- Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms (CSUCH). [cited 2024 Apr 1]. Available from: https://csuch.ca/explore-the-data/47.

- Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General. Motor vehicle incident deaths 2012-2021 [Internet]. 2022 Apr p. 1–10. Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/statistical/motor_vehicle_ incident_deaths_2012-2021.pdf.

- BC Coroners Service (BCCS). BC Coroners Service (BCCS) suicide Data – knowledge Update to December 31, 2021 [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/statistical/ suicide_knowledge_update.pdf47.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Tobacco Fact Sheet [Internet]. World Health Organization (WHO); 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Health Effects of Cigarette Smoking [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2021 [cited 2022 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm#:~:text=Cigarette%20smoking%20is%20the%20leading,death%20in%20the%20United%20 States.&text=Cigarette%20smoking%20causes%20more%20than,nearly%20one%20in%20five%20deaths

- Health Canada. Tobacco and Premature Death [Internet]. Government of Canada; 2023 [cited 2024 Sept 3]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/tobacco/legislation/tobacco-product-labelling/smoking-mortality.html

- Health Canada. Smoking and Mortality [Internet]. Health Canada; 2011 [cited 2022 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/ health-canada/services/health-concerns/tobacco/legislation/tobacco-product-labelling/smoking-mortality.html#a1

- Canadian Cancer Society. Cigarettes-the hard truth [Internet]. Canadian Cancer Society. Available from: https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/reduce-your-risk/live-smoke-free/cigarettes-the-hard-truth

- Giulietti F, Filipponi A, Rosettani G, Giordano P, Iacoacci C, Spannella F, Sarzani R. Pharmacological Approach to Smoking Cessation: An Updated Review for Daily Clinical Practice. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2020 Oct;27(5):349-362. doi: 10.1007/s40292-020-00396-9. Epub 2020 Jun 23. PMID: 32578165; PMCID: PMC7309212

- Tan J, Zhao L, Chen H. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of gradual versus abrupt smoking cessation [Internet]. [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.journalssystem.com/tid/A-Meta-Analysis-of-the-effectiveness-of-gradual-vs-abrupt-smokingcessation,100557,0,2.html

- 10 common myths about smoking and quitting - Tobacco and smoking [Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 29]. Available from: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au:443/tobacco/Pages/myths-about-smoking-and-quitting.aspx

- American College of Cardiology. Clinician Tool: Tobacco Cessation for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease [Internet]. American College of Cardiology; 2018 [cited 2023 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.acc.org/~/media/0D3B2F4EE12A49D2995E8D7A734AC486.pdf

- Rankin KV, Jones DL. Prevention strategies for oral cancer. Prevention in Clinical Oral Health Care. 2008;230–43. doi:10.1016/b978-0- 323-03695-5.50021-5

- Pack QR, Priya A, Lagu TC, Pekow PS, Atreya A, Rigotti NA, et al. Short‐term safety of nicotine replacement in smokers hospitalized with coronary heart disease. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2018 Sept 18;7(18). doi:10.1161/jaha.118.009424

- Ottawa Model for Smoking Cessation. Smoking FAQs [Internet]. Available from: https://ottawamodel.ottawaheart.ca/education/ frequently-asked-questions

- Rigotti N. Pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation in adults. UpToDate [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2022 Oct 1]; Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-for-smoking-cessation-in-adults

- Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Ahluwalia JS, Russell C, Maglia M, Riela PM, et al. Varenicline and counseling for vaping cessation: a double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Med. 2023 Jul 5;21(1):220.

- Smoking cessation: Other medications for smoking cessation [Internet]. CAMH. Available from: https://www.camh.ca/en/professionals/ treating-conditions-and-disorders/smoking-cessation/smoking-cessation---treatment/smoking-cessation---other-medications-forsmoking-cessation#:~:text=Combining%20bupropion%20with%20other%20smoking,this%20increases%20chances%20of%20quitting.

- Lee JH, Jones PG, Bybee K, O’Keefe JH. A longer course of varenicline therapy improves smoking cessation rates. Prev Cardiol. 2008;11(4):210–4

- Tonstad S, Tønnesen P, Hajek P, Williams KE, Billing CB, Reeves KR, et al. Effect of maintenance therapy with varenicline on smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006 Jul 5;296(1):64–71.

- CAMH Nicotine Dependence Services. Tobacco Use, Mental Illness & Substance Use Disorders: What’s the link? [Internet]. CAMH Nicotine Dependence Services; n.d. [cited 2022 Oct 5]. Available from: https://www.nicotinedependenceclinic.com/en/teach/ Documents/Tobacco%20Use,%20Mental%20Illness%20and%20Substance%20Use%20Disorders.pdf

- Giulietti F, Filipponi A, Rosettani G, Giordano P, Iacoacci C, Spannella F, Sarzani R. Pharmacological Approach to Smoking Cessation: An Updated Review for Daily Clinical Practice. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2020 Oct;27(5):349-362. doi: 10.1007/s40292-020-00396-9. Epub 2020 Jun 23. PMID: 32578165; PMCID: PMC7309212

- Brady KT. Social Determinants of Health and Smoking Cessation: A Challenge. Am J Psychiatry. 2020 Nov 1;177(11):1029–30.

- Ministry of Health. What is vaping? [Internet]. Government of British Columbia [cited 2024 Sept 2]. Available from: What is vaping? - Province of British Columbia (gov.bc.ca)

- Smith A, Poon C, Peled M, Forsyth K, Saewyc E, McCreary Centre Society. The Big Picture: An overview of the 2023 BC Adolescent Health Survey provincial results [Internet]. McCreary Centre Society; 2024. Available from: https://mcs.bc.ca/pdf/2023_bcahs_the_big_picture.pdf

- QuitNow BC. Learn about nicotine addiction [Internet]. QuitNow BC; [cited 2024 Sept 2]. Available from: https://quitnow.ca/explorequitnow/learn-about-quitting/learn-about-nicotine

- Hammond D, Reid J, East K, Burkhalter R. Evaluating provincial vaping policies among young people in British Columbia [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://www.vch.ca/sites/default/files/import/documents/Evaluating-provincial-vaping-policies-among-youngpeople-in-British-Columbia.pdf51.

- Hair EC, Barton AA, Perks SN, Kreslake JM, Xiao H, Pitzer L, et al. Association between e-cigarette use and future combustible cigarette use: Evidence from a prospective cohort of youth and young adults, 2017–2019. Addictive Behaviors [Internet]. 2021 Jan 1;112:106593. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32927247/

- Health Canada. Talking with your teen about vaping: A tip sheet for adults [Internet]. Health Canada. Health Canada; 2019 [cited 2024 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/themes/health/publications/healthy-living/vaping-mechanics-infographic/Parent%20tip%20sheet_web_Final_EN.pdf48.

- Hammond D, Reid J, East K, Burkhalter R. Evaluating provincial vaping policies among young people in British Columbia [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://www.vch.ca/sites/default/files/import/documents/Evaluating-provincial-vaping-policies-among-youngpeople-in-British-Columbia.pdf51.

- Tobacco industry interference [Internet]. Truth Initiative. 2020 Sep. Available from: https://truthinitiative.org/our-top-issues/industryinfluence

- East K PhD, O’Connor RJ, Hammond D PhD. Vaping products in Canada: A market scan of E-Liquid products, flavours, and nicotine content [Internet]. University of Waterloo, Canada. 2022 Oct. Available from: https://davidhammond.ca/wp-content/ uploads/2024/04/2021-E-cigarette-retail-scan-report-East-Hammond.pdf.

- Hammond D, East K, Wiggers D, Mahamad S. Vaping products in Canada [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://davidhammond.ca/ wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2020-Vaping-Packaging-Final-Report-Hammond-Dec-15.pdf

- World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2019: offer help to quit tobacco use [Internet [Internet]. Vol. Aug 23. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. p. 209. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/326043

- The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). Vaping Cessation Guidance Resource [Internet]. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH); 2022 [cited 2024 Sept 2]. Available from: https://www.nicotinedependenceclinic.com/en/Documents/Vaping%20Cessation%20Guidance%20Resource.pdf

- Canadian Paediatric Society [Internet]. Canadian Paediatric Society; 2021 [cited 2024 Sept 2]. Available from: https://cps.ca/documents/ position/protecting-children-and-adolescents-against-the-risks-of-vaping

- Hartmann-Boyce J, Lindson N, Butler AR, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Begh R, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2022 Nov 17 [cited 2022 Oct 1];2023(2). Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub7

- Grabovac I, Oberndorfer M, Fischer J, Wiesinger W, Haider S, Dorner TE. Effectiveness of Electronic Cigarettes in Smoking Cessation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021 Mar;19;23(4):625–34.

- Butler AR, Lindson N, Fanshawe TR, Theodoulou A, Begh R, Hajek P. Longer-term use of electronic cigarettes when provided as a stop smoking aid: Systematic review with meta-analyses. Prev Med. 2022 Aug;

- Lindson N, Theodoulou A, Ordóñez‐Mena JM, Fanshawe TR, Sutton AJ, Livingstone‐Banks J, et al. Pharmacological and electronic cigarette interventions for smoking cessation in adults: component network meta-analyses. Cochrane Library [Internet]. 2023 Sep 12;2023(9). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd015226.pub2

- Karnieg T, Wang X. Cytisine for smoking cessation. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal [Internet]. 2018 May 14;190(19):E596. Available from: https://www.cmaj.ca/content/190/19/e596

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Heated Tobacco Products [Internet]. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH); 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 15]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/heated-tobacco-products/index.html

- Tattan-Birch H, Hartmann-Boyce J, Kock L, Simonavicius E, Brose L, Jackson S, et al. Heated tobacco products for smoking cessation and reducing smoking prevalence. Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2022 Jan 6 [cited 2022 Oct 5];2022(4). Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD013790.pub2

- World Health Organization. Heated tobacco Products information sHeet [Internet]. 2nd ed. Heated Tobacco Products Information sHeet. 2020 Mar. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/331297/WHO-HEP-HPR-2020.2-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- White A, Rampes H, Liu J, Stead LF, Campbell J. Acupuncture and related interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Library [Internet]. 2014 Jan 23;2014(1). Available from: https://www.cochrane.org/CD000009/TOBACCO_do-acupuncture-and-related-therapieshelp-smokers-who-are-trying-to-quit#:~:text=Although%20pooled%20estimates%20suggest%20possible,firm%20conclusions%20 can%20be%20drawn

- Barnes J, McRobbie H, Dong C, Walker N, Hartmann‐Boyce J. Hypnotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Library [Internet]. 2019 Jun 14;2019(6). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd001008.pub3

- Lindson N, Theodoulou A, Ordóñez‐Mena JM, Fanshawe TR, Sutton AJ, Livingstone‐Banks J, et al. Pharmacological and electronic cigarette interventions for smoking cessation in adults: component network meta-analyses. Cochrane Library [Internet]. 2023 Sep 12;2023(9). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd015226.pub2

- Jackson S, Brown J, Norris E, Livingstone-Banks J, Hayes E, Lindson N. Mindfulness for smoking cessation. Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2022 Apr 14 [cited 2022 Oct 5];2022(4). Available from: http://doi.wiley. com/10.1002/14651858.CD013696.pub2

- Fanshawe TR, Hartmann-Boyce J, Perera R, Lindson N. Competitions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2019 Feb 20 [cited 2022 Oct 5];2019(2). Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858. CD013272

- Walia N, Gonzalez S, Zoorob R. A Systematic Review of the Use of St. John’s Wort for Smoking Cessation in Adults. Cureus. 2021 Oct 14;13(10):e18769. doi: 10.7759/cureus.18769. PMID: 34796061; PMCID: PMC8590314.

- Lengel D, Kenny PJ. New medications development for smoking cessation. Addiction Neuroscience [Internet]. 2023 Sep 1;7:100103. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772392523000469

- Canadian Paediatric Society [Internet]. Canadian Paediatric Society; 2021 [cited 2024 Sept 2]. Available from: https://cps.ca/documents/position/protecting-children-and-adolescents-against-the-risks-of-vaping

- Livingstone-Banks J, Fanshawe TR, Thomas KH, Theodoulou A, Hajizadeh A, Hartman L, Lindson N. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2023, Issue 6. Art. No.: CD006103. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub9.

|

BC Guidelines are developed for the Medical Services Commission by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, a joint committee of Government and the Doctors of BC. BC Guidelines are adopted under the Medicare Protection Act and, where relevant, the Laboratory Services Act. Disclaimer: This guideline is based on best available scientific evidence and clinical expertise as of October 24, 2024. It is not intended as a substitute for the clinical or professional judgment of a health care practitioner. |