Colorectal Cancer Part 1

Part 1: Screening for the Purposes of Colorectal Cancer Prevention and Detection in Asymptomatic Adults

Effective Date: April 13, 2022

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Epidemiology

- Major Risk Factors

- Primary Prevention

- Screening Strategies

- Risks and Benefits of Screening Modalities

- Resources

Scope

This guideline provides recommendations for the detection of colorectal cancer (CRC) and precancerous lesions in asymptomatic adults, including identifying those whose family histories suggest hereditary syndromes (see Appendix A: Hereditary Colorectal Cancer [CRC] Syndromes). It does not apply to patients with anemia, or bowel related symptoms or signs, which should be evaluated directly via diagnostic tests, rather than via the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) screening test. It also does not apply to patients with inflammatory bowel disease whose CRC prevention should be individualized. Recommendations following removal of colorectal precancerous lesions or cancer can be found at BCGuidelines.ca: Follow-up of Colorectal Cancer and Precancerous Lesions (Polyps).

Key Recommendations

- Screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) should be based on risk stratification, which determines the appropriate screening test and interval.

- Wherever possible, patients should be encouraged to have their initial screening and follow-up conducted through the British Columbia (BC) Colon Screening Program (CSP), even if they have previously been screened outside of the program.

- Fecal immunochemical test (FIT) every 2 years is the preferred screening strategy for average-risk individuals age 50 – 74.

- Since a positive FIT is specific for the presence of human blood, any positive FIT should be followed up with colonoscopy. Do not repeat the FIT.

- FIT is not necessary when frank blood is present. Those individuals should be directly investigated via diagnostic tests rather than the FIT screening test.

- Individuals at average risk for CRC, who have had a colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy within the last 10 years with no precancerous lesions identified do not require additional screening.

- Individuals with a family history of CRC should follow different age and frequency screening criteria:

- 2 or more first-degree relatives (FDRs) with CRC diagnosed at any age: colonoscopy every 5 years starting at age 40 or starting 10 years younger than the age of diagnosis of the earliest affected relative.

- 1 FDR with CRC diagnosed before age 60 years: colonoscopy every 5 years starting at age 40 or starting 10 years younger than the age of diagnosis of the affected relative.

- 1 FDR with CRC diagnosed after age 60 years: FIT every 2 years starting at age 50.

- 1 or more second-degree relatives with CRC at any age: FIT every 2 years starting at age 50.

- Hereditary CRC syndromes and recommended screening are addressed in Appendix A: Hereditary Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Syndromes.

Epidemiology

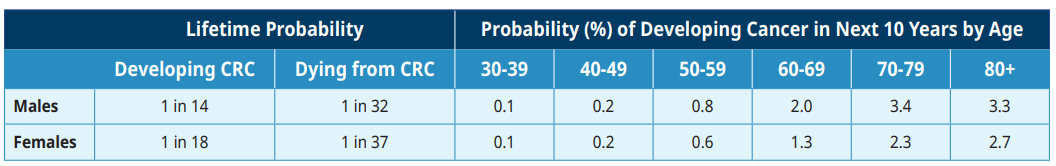

CRC ranks as the third most common malignancy in Canada and the second most frequent cause of cancer death.1 The incidence of CRC rises steadily after the age of 50. More than 1300 people die each year from CRC in BC.1 The age-standardized incidence rate of CRC in BC in 2019 was 72.3/100,000 men and 51.3/100,000 women.1

Table 1: Lifetime Probability of Developing or Dying from Colorectal Cancer (CRC) in Canada1

Most CRCs arise from precancerous lesions (previously known as polyps); as it generally takes 5 to 10 years for a small precancerous lesion to develop into a malignancy, cancer may be prevented by removal of such a lesion.3 Two major types of precancerous lesions are found in the colon and rectum: adenomas and serrated lesions. Amongst the serrated lesions, sessile serrated lesions (SSLs) and traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs) are considered to have the potential for malignant transformation while hyperplastic polyps (HPs) do not. Individuals with multiple precancerous lesions of any size are at increased risk of CRC.2

The risk of a precancerous lesion becoming malignant is greatest for ‘high risk’ lesions (also known as advanced adenomas), which are defined as having any of the following:

- adenomas with villous features

- adenomas with high grade dysplasia

- adenomas or sessile serrated lesion (SSL) ≥ 10 mm (as measured by the colonoscopist at the time of excision)

- sessile serrated lesions (SSLs) with cytologic dysplasia

- traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs)

- hyperplastic polyps ≥ 10 mm (as measured by the colonoscopist at the time of excision)

Major Risk Factors

The most important risk factor for CRC is increasing age over 50.3,4

Other major risk factors for CRC include:2,4

- Personal history of high-risk precancerous lesions (advanced adenoma, see above).

- Family history of CRC:

- FDR* with CRC under age 60.5

- Two or more FDRs with CRC at any age.

- Hereditary CRC syndrome such as Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), LynchSyndrome or hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC). See Appendix A: Hereditary Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Syndromes.

- Individuals with long-standing and extensive inflammatory bowel disease. These patients require an individualized approach to dysplasia detection, distinct from the recommendations in this guideline, guided by an inflammatory bowel disease specialist.

Approximately 75% of all CRC occurs in patients of average risk with no family history.4 A second degree relative with CRC does not significantly increase one’s risk of CRC. There is no evidence that people with other sporadic cancers (e.g., breast, prostate, lung) are at increased risk of developing CRC.

Additional risk factors for CRC include a diet rich in red and processed meat and low in fruits and vegetables, smoking, sedentary lifestyle and obesity, diabetes, and alcohol consumption, but there is currently insufficient evidence to modify screening recommendations based on these modest risk factors.

Certain populations are less likely to have been screened and are therefore indirectly at higher risk for CRC, i.e., First Nations, Inuit and Métis, low-income individuals, rural and remote communities, and new immigrants.2

* 1st degree relatives have a blood relationship to the patient: parents, brothers, sisters and children. 2nd degree relatives have a blood relationship to the patient: aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, grandparents & grandchildren.

Primary Prevention

Other than individuals who are already taking Acetylsalicylic Acid (ASA) for cardiovascular disease up to age 70, there is currently no value in ASA intake for prevention of CRC.3 However, higher dose ASA (600 mg per day) is associated with decreased risk of CRC in Lynch Syndrome patients.4

Several other medications, vitamins, supplements, and dietary factors have been evaluated as chemoprotective agents for CRC but have not been shown to be effective with any degree of certainty.5

Screening Strategies

BC Colon Screening Program (CSP)

Wherever possible, patients should be referred by their primary care practitioner to have their initial screening and follow-up conducted through the BC Colon Screening Program (CSP), even if they have previously been screened outside of the program. To learn more, see associated documents. The intention is that these patients will be recalled by the CSP at the appropriate interval.

It is estimated that up to 60% of patients who qualify for screening are not registered in the CSP and may therefore run some risk of being lost to follow-up. Issues contributing to loss of follow-up include orphaned patients, patient and practitioner mobility, and significant time intervals between re-screening and for surveillance. These issues underscore the importance of patients being engaged in their care plans.

Maintaining an up-to-date registration with the CSP will assure patients receive their mailed follow-up reminders. The program offers patients navigator services when colonoscopy is required.

These guidelines and approach to patient care need to be balanced against individual factors and clinical judgement of the practitioners involved.

Individuals with significant family history of CRC

Significant family history includes those with 2 or more FDRs with CRC diagnosed at any age or 1 FDR with CRC diagnosed before age 60 years.

These individuals should be offered a colonoscopy every 5 years at age 40 years, or 10 years younger than the age of diagnosis of the affected relative. There is no need for FIT testing in this population.

Hereditary CRC syndromes and recommended screening are addressed in Appendix A: Hereditary Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Syndromes. Referrals can be made to the Hereditary Cancer Program at the BC Cancer Agency, see www.bccancer.bc.ca

Average risk asymptomatic individuals, aged 50 to 74 years6

For most individuals in this group, the primarily recommended strategy is FIT every 2 years,7,8 with any positive FIT to be followed by a colonoscopy.7 After a negative colonoscopy, screening with FIT can be delayed for a 10 year interval.

More invasive alternatives to regular FIT screening include, flexible sigmoidoscopy (every 10 years), colonoscopy (every 10 years) or computed tomography (CT) colonography (every 5 years). Of these options, only FIT every 2 years and flexible sigmoidoscopy every 10 years are recommended by the Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health.6

It should be noted that those with 1 FDR with CRC diagnosed after 60 years or 1 or more second-degree relatives with CRC at any age are not at increased risk.

Average risk asymptomatic individuals, age 75 years and older

Recognizing the generally long time course for development of cancer from precancerous lesions (polyps) in individuals who have been regularly screened up to age 75 years, it is recommended to discontinue screening by FIT or other modalities after age 75.12,13 However, for older individuals, the value of screening should be individually assessed taking into account a balance of the risks, benefits, patient comorbidities, frailty7,8 and anticipated life expectancy. A previously unscreened individual may benefit from a one time screening test over 75 years.9

Screening is not recommended after 85 years of age.13

Controversies in Care

Average risk asymptomatic individuals, under age 50 years and with no family history

For reasons not yet fully understood, the incidence of early onset CRC is increasing in Canada and other countries.10 Early onset CRC is defined as CRC diagnosed under the age of 50 years. Preliminary studies suggest an association with a lower income, obesity, and a more sedentary lifestyle.11 American CRC screening guidelines have recommended initiating screening at 45 years of age, acknowledging that this recommendation is based on low quality evidence.12,13 However, to our knowledge all other countries with screening guidelines, have continued to commence screening at age 50 years.14,15 While relative rates of early onset CRC have been increasing, the absolute number diagnosed in the 45 – 49 year age group remains low (1 in 18,000 in 2012 to 2016 versus 1 in 19,000 in 1992 to 1996).11 At this time, screening average risk individuals under the age of 50 years is not recommended.

Physicians should be mindful of the increasing incidence of CRC in younger adults when evaluating symptomatic patients.

Risks and Benefits of Screening Modalities

All screening modalities have associated benefits and harms, including the risk of missing a precancerous lesion (previously referred to as polyp) or CRC, but an effective screening technique for CRC should be feasible, accurate, safe, acceptable, and cost-effective.

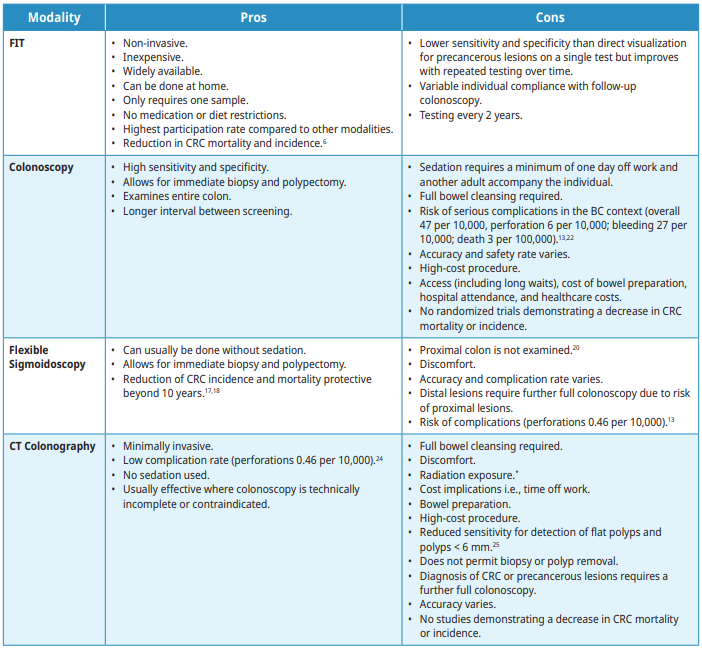

The following screening modalities are available with the pros and cons outlined in Table 2: Summary of risks and benefits. Tests that are not recommended for screening are listed. For individuals who test positive on any non-colonoscopy screening test, a full colonoscopy is advised.

-

Fecal Immunochemical test (FIT)

FIT is recommended every 2 years. Performing the test through the BC Colon Screening program (CSP) is the preferred method for CRC screening in BC where it is coordinated by a nurse navigator and a patient recall system with quality assurance initiatives. When used in the appropriate population, FIT is the most cost-effective strategy.15 Any individual with a positive FIT should be referred for colonoscopy. Individuals at higher risk for CRC who are undergoing regular colonoscopy screening should not have a FIT. Individuals who report frank blood in the stool or have other symptoms concerning for CRC should not have FIT. FIT’s sensitivity for cancer as performed in BC is approximately 90%.16 When used repeatedly every 2 years it becomes an increasingly sensitive strategy for detecting precancerous lesions (polyps).

-

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy is the recommended test following a positive FIT, a flexible sigmoidoscopy in which CRC or precancerous lesions (polyps) are identified, or a CT colonography in which CRC or precancerous lesions are identified. During colonoscopy, precancerous lesions (polyps) are removed to prevent the development of CRC.2,3,23 Colonoscopy examines the entire colon and requires an oral bowel preparation. The recommended screening interval following a colonoscopy in which no precancerous lesions or CRC are identified is 10 years for average risk patients. Complications can arise from the bowel preparation as well as the procedure.

-

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

Flexible sigmoidoscopy examines the rectum and sigmoid colon. It can usually be done without intravenous sedation but does require colon preparation, which may be given orally or via enema.9 The recommended screening interval after a flexible sigmoidoscopy with no pre-cancerous lesions identified is 10 years.

-

Computed tomography (CT) Colonography

CT colonography images the entire colon utilizing a CT scanner. It requires a thorough bowel preparation, pre-procedure ingestion of fecal and fluid tagging agents, and spasmolytic (e.g.,Buscopan®). The colon and rectum are insufflated with carbon dioxide gas through a retention tube inserted into the rectum. The patient is positioned in the scanner in supine and prone or decubitus positions and scans acquired. CT colonography imaging of extraluminal structures is limited because intravenous contrast is not administered. Complications such as abdominal cramping or diarrhea can arise from the bowel preparation or CO2 insufflation, but typically resolve within a short period of time. The usual interval for CT Colonography is 5 years if no precancerous lesions (polyps) are identified, if the patient chooses not to use FIT.

Table 2: Summary of CRC screening modality risks and benefits

*Radiation dose for CTC is difficult to determine precisely as it is dependent on multiple factors including patients’ body habitus and how many scans/views are needed. Protocols used are based on patient size and composition and aim to reduce dose as much as possible. Average radiation doses are approximately 7mSv (equivalent to 70 CXRs or 2 years background radiation).19,20

-

Tests Not Recommended for Screening

Evidence does not support the use of the following as primary screening tools for CRC in asymptomatic patients:

- Barium enemas

- Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) tests

- Combined use of FIT with flexible sigmoidoscopy for primary screening

Resources

References

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2019 [Internet]. Canadian Cancer Society; 2019 [cited 2021 Jul 12]. Available from: cancer.ca/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2019-EN

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Equity-focused interventions to increase colorectal cancer screening: Program Pack [Internet]. Canadian Partnership Against Cancer; 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/topics/equity-colorectal-cancer-screening/

- Guo C-G, Ma W, Drew DA, Cao Y, Nguyen LH, Joshi AD, et al. Aspirin Use and Risk of Colorectal Cancer Among Older Adults. JAMA Oncol. 2021 Mar 1;7(3):428.

- Burn J, Sheth H, Elliott F, Reed L, Macrae F, Mecklin J-P, et al. Cancer prevention with aspirin in hereditary colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome), 10-year follow-up and registry-based 20-year data in the CAPP2 study: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2020 Jun;395(10240):1855–63.

- Chapelle N, Martel M, Toes-Zoutendijk E, Barkun AN, Bardou M. Recent advances in clinical practice: colorectal cancer chemoprevention in the average-risk population. Gut. 2020 Dec;69(12):2244–55.

- Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on screening for colorectal cancer in primary care. Can Med Assoc J. 2016 Mar 15;188(5):340–8.

- Howard R, Machado-Aranda D. Frailty as a Predictor of Colonoscopic Procedural Risk: Robust Associations from Fragile Patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2018 Dec;63(12):3159–60.

- Oberndorfer T, Jurawan R. Frailty should be assessed in older patients considered for colonoscopy. N Z Med J [Internet]. 2021 Jul 30 [cited 2021 Dec 10];134(134). Available from: https://journal.nzma.org.nz/journal-articles/frailty-should-be-assessed-in-older-patients-considered-for-colonoscopy

- van Hees F, Zauber AG, Klabunde CN, Goede SL, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M. The Appropriateness of More Intensive Colonoscopy Screening Than Recommended in Medicare Beneficiaries: A Modeling Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Oct 1;174(10):1568.

- Brenner DR, Heer E, Sutherland RL, Ruan Y, Tinmouth J, Heitman SJ, et al. National Trends in Colorectal Cancer Incidence Among Older and Younger Adults in Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Jul 31;2(7):e198090.

- Decker KM, Lambert P, Bravo J, Demers A, Singh H. Time Trends in Colorectal Cancer Incidence Rates by Income and Age at Diagnosis in Canada From 1992 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Jul 19;4(7):e2117556.

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021 May 18;325(19):1965.

- Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, Flowers CR, Guerra CE, LaMonte SJ, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society: ACS Colorectal Cancer Screening Guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Jul;68(4):250–81.

- National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia), Australian Cancer Network, Cancer Council Australia. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of colorectal cancer. [Internet]. Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network; 2005 [cited 2021 Sep 16]. Available from: https://wiki.cancer.org.au/australia/Guidelines:Colorectal_cancer

- Argilés G, Tabernero J, Labianca R, Hochhauser D, Salazar R, Iveson T, et al. Localised colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020 Oct;31(10):1291–305.

- Imperiale TF, Gruber RN, Stump TE, Emmett TW, Monahan PO. Performance Characteristics of Fecal Immunochemical Tests for Colorectal Cancer and Advanced Adenomatous Polyps: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Mar 5;170(5):319.

- Tinmouth J, Vella ET, Baxter NN, Dubé C, Gould M, Hey A, et al. Colorectal Cancer Screening in Average Risk Populations: Evidence Summary. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:1–18.

- Senore C, Riggi E, Armaroli P, Bonelli L, Sciallero S, Zappa M, et al. Long-Term Follow-up of the Italian Flexible Sigmoidoscopy Screening Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2021 Nov 9;M21-0977.

- van Gelder RE, Florie J, Stoker J. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance with CT colonography: current controversies and obstacles. Abdom Imaging. 2004 Jan;30(1):5–12.

- Tolan DJM, Armstrong EM, Burling D, Taylor SA. Optimization of CT colonography technique: a practical guide. Clin Radiol. 2007 Sep;62(9):819–27.

- Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM, Giardiello FM, Hampel HL, Burt RW. ACG Clinical Guideline: Genetic Testing and Management of Hereditary Gastrointestinal Cancer Syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Feb;110(2):223–62.

- Rubenstein JH, Enns R, Heidelbaugh J, Barkun A, Adams MA, Dorn SD, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Diagnosis and Management of Lynch Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2015 Sep;149(3):777–82.

Abbreviations

ASA

CEA

CRC

CT

FAP

FDR

FIT

FOBT

FS

HNPCC

HP

MAP

SSL

TSA

Acetylsalicylic Acid

Carcinoembryonic Antigen

Colorectal cancer

Computed tomography

Familial adenomatous polyposis

First-degree relative

Fecal immunochemical test

Fecal Occult Blood Test

Flexible sigmoidoscopy

Hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer

Hyperplastic polyps

MUTYH Associated Polyposis

Sessile serrated lesions

Traditional serrated adenomas

Practitioner resources

- BC Colon Screening Program: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/screening/colon

- Hereditary Cancer Program at the BC Cancer Agency: www.bccancer.bc.ca

- Pathways: https://pathwaysbc.ca/login

- UBC CPD BC Cancer Primary Care Learning Sessions - Colorectal Cancer: https://elearning.ubccpd.ca/

- Canadian Cancer Society: www.cancer.ca

- Colon Cancer Canada: www.coloncancercanada.ca

- Public Health Agency of Canada: Cancer

Patient, Family and Caregiver resources

- BC Colon Screening Program: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/screening/colon

- BC Colon Screening: Facts and Myths

- BC Cancer: Hereditary Cancer Program

- HealthlinkBC: Health information, translation services, Health Service Navigators and dieticians, www.healthlinkbc.ca or by telephone at 811.

- Canadian Cancer Society: www.cancer.ca

- Colon Cancer Canada: www.coloncancercanada.ca

- Public Health Agency of Canada: Cancer

Appendices

Appendix A: Hereditary Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Syndromes (PDF, 121KB)

Associated Documents

The following documents accompany this guideline:

- BCGuidelines.ca: Follow-up of Colorectal Cancer and Precancerous Lesions (Polyps)

- BC Cancer: Referral Page

- BC Cancer: Colon Screening Program: Colonoscopy Referral Form

- BC Cancer: Standard Out-Patient Laboratory Requisition Form

- Associated Document - List of Contributors (PDF, 61KB)

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the effective date.

This guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee in collaboration with the Provincial Laboratory Medicine Services, and adopted under the Medical Services Act and the Laboratory Services Act.

For more information about how BC Guidelines are developed, refer to the GPAC Handbook available at

BCGuidelines.ca: GPAC Handbook.

THE GUIDELINES AND PROTOCOLS ADVISORY COMMITTEE

|

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

Contact Information: Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee PO Box 9642 STN PROV GOVT Victoria, BC V8W 9P1 Email: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca Website: www.BCGuidelines.ca

Disclaimer The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the guidelines) have been developed by the guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional. |

TOP

TOP