High-Risk Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder

Effective Date: February 21, 2024

Recommendations and Topic

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Risk Factors

- Principles of Care

- Alcohol Use Screening

- Diagnosis of AUD

- Management

- Pharmacological Management

- Ongoing Care - Psychosocial treatment interventions

- Resources

Scope

Screening for alcohol use and alcohol use disorder (AUD) is important, given its impact on acute and chronic conditions, relationships, and other aspects of well-being. Evidence supports routine screening in primary care practice. This guideline aims to support clinicians in identifying and managing high-risk drinking (HRD) and AUD in adults and youth. This guideline adapts the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use’s (BCCSU) Provincial Guideline for the Clinical Management of High-Risk Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder (2019) and the Canadian Guideline for the Clinical Management of High-Risk Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder (2023).

Key Recommendations

Practitioners should examine their preconceptions or biases regarding alcohol use, who uses it, and how it is used. Differentiate between high-risk alcohol use and alcohol use disorders. Consider how to investigate and communicate alcohol related diagnoses, being mindful of potential stigmatization and bias in care. See associated documents for examples.

Screening and Brief Intervention

- Screen all patients routinely for alcohol use above low-risk limits. [Certainty of Evidence: Low, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

- Screen youth patients for alcohol use with the Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble (CRAFFT) instrument (see associated documents) or the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Screening Tool. [Certainty of Evidence: Moderate, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

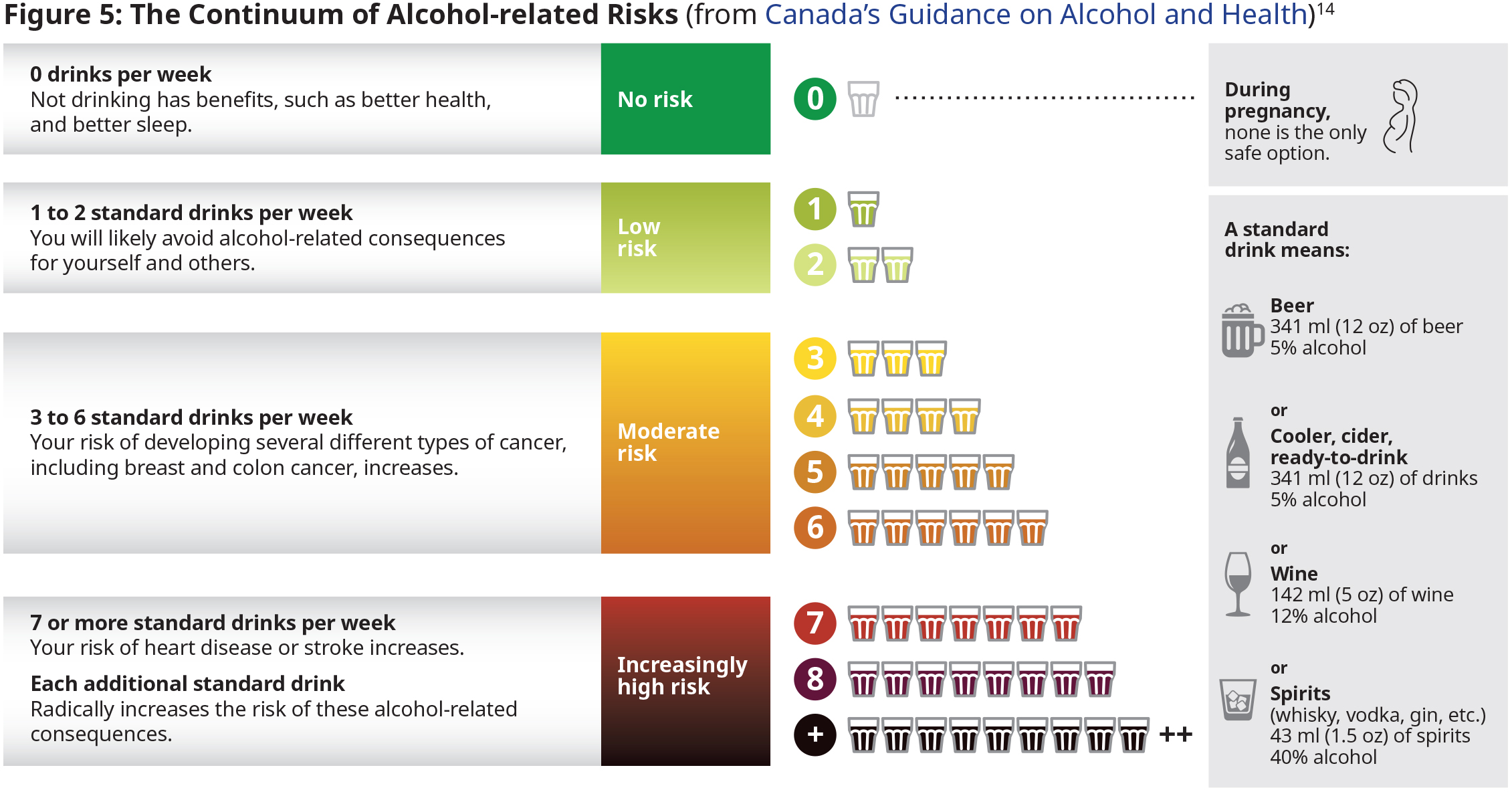

- To facilitate discussions about alcohol use, when appropriate, ask patients about current knowledge of and offer education about Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health. [Certainty of Evidence: Low, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

- Assess patients who screen positive for high-risk alcohol use or for AUD (See DSM-5-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Alcohol Use Disorder). [Certainty of Evidence: Low, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

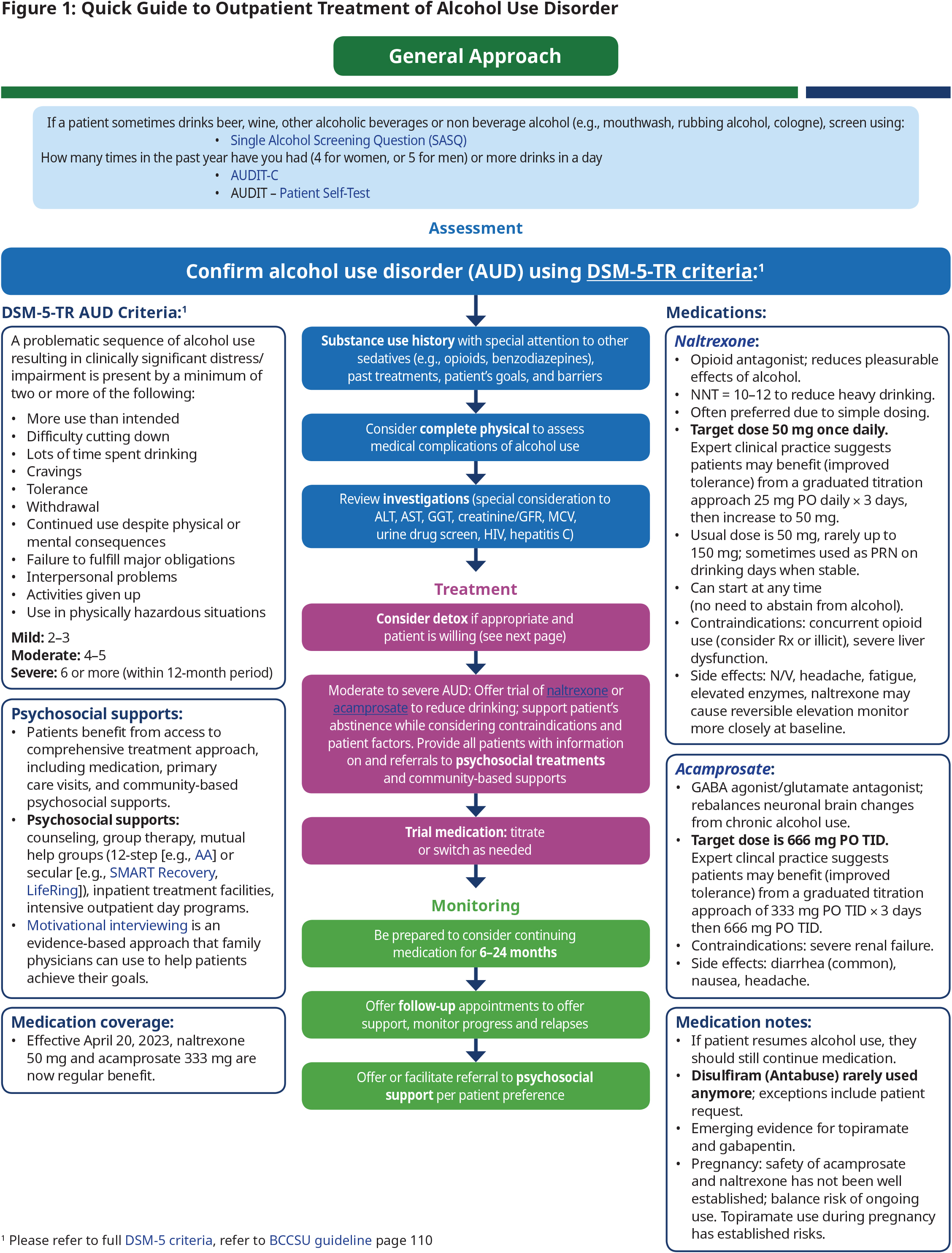

- Use brief intervention for all patients who screen positive for alcohol use at moderate or high-risk limits but who do not meet the criteria for AUD (see Figure 1: Quick Guide to Outpatient Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder). [Certainty of Evidence: Moderate, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

- Consider using a motivational interviewing-based approach to support achieving treatment goals. [Certainty of Evidence: Moderate, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

Withdrawal Management

- Use Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS) to identify the most appropriate withdrawal management pathway. PAWSS is a validated tool for assessing the risk of severe complications of alcohol withdrawal. See associated documents for criteria. [Certainty of Evidence: Moderate, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

- For patients at low risk of severe complications of alcohol withdrawal (ie., PAWSS < 4), consider prescribing alternatives to benzodiazepines, e.g., gabapentin, carbamazepine and/or adjuvants such as clonidine for withdrawal management in an outpatient setting. [Certainty of Evidence: Moderate (gabapentin) Low (carbamazepine, clonidine), Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

- For patients at high risk of severe withdrawal complications (ie., PAWSS ≥ 4), offer a short-term benzodiazepine prescription. This is ideally completed in an inpatient setting (i.e., a withdrawal management facility or hospital). Where inpatient admission is not available, benzodiazepine medications can be offered to patients in outpatient settings if they can be closely monitored and supported. [Certainty of Evidence: High, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

- Do not prescribe benzodiazepines as ongoing treatment for AUD. [Certainty of Evidence: High, Strength of Recommendation: Strong]

- When possible, patients who complete withdrawal management should be offered continuing care. Withdrawal management is a short-term intervention that does not resolve the underlying medical, psychological, or social issues of AUD and should be considered a bridge to continuing care. [Certainty of Evidence: Low, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

- Patients should not be prescribed antipsychotics or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) antidepressants if the primary reason is for the treatment of AUD. If SSRI antidepressants are prescribed for individuals with co-occurring mood disorders, clinicians and patients should be alert to the risk of increased alcohol cravings and use with SSRI therapy and discontinue as appropriate.1 [Certainty of Evidence: Strong, Strength of Recommendation: Moderate.]

Continuing Care

- Consider offering naltrexone or acamprosate to adult patients with moderate to severe AUD. These are first-line pharmacotherapy agents that may support patient-identified treatment goals.

- Naltrexone is recommended for patients who have a treatment goal of either abstinence or a reduction in alcohol consumption. [Certainty of Evidence: High, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

- Acamprosate is recommended for patients who have a treatment goal of abstinence. [Certainty of Evidence: High, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

- Consider offering topiramate to adult patients with moderate to severe AUD who do not benefit from or have contraindications to first-line medications. Some patients may express a preference for topiramate or gabapentin.

- Topiramate. [Certainty of Evidence: Moderate, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

- Gabapentin. [Certainty of Evidence: Low, Strength of Recommendation: Conditional.]

- Consider providing information about and referrals to specialist-led psychosocial treatment interventions to all patients with AUD. See the resource section for referral and specialist information. [Certainty of Evidence: Moderate, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

- Consider providing all patients with AUD information about and referrals to peer-support services, harm reduction interventions and/or other recovery-oriented services in the community. [Certainty of Evidence: Moderate, Strength of Recommendation: Strong.]

Definition

- AUD is a chronic relapsing and remitting medical condition attributed to an impaired capability to regulate alcohol use regardless of detrimental health, social or occupational repercussions.2 The diagnosis of an AUD is made using the DSM-5-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Alcohol Use Disorder.

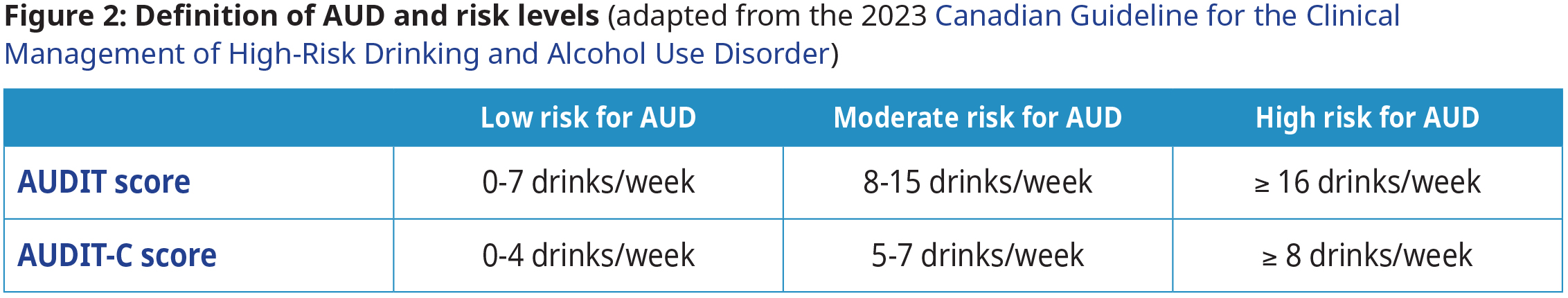

This guideline uses different low- and high-risk definitions based on the validated screening tools.

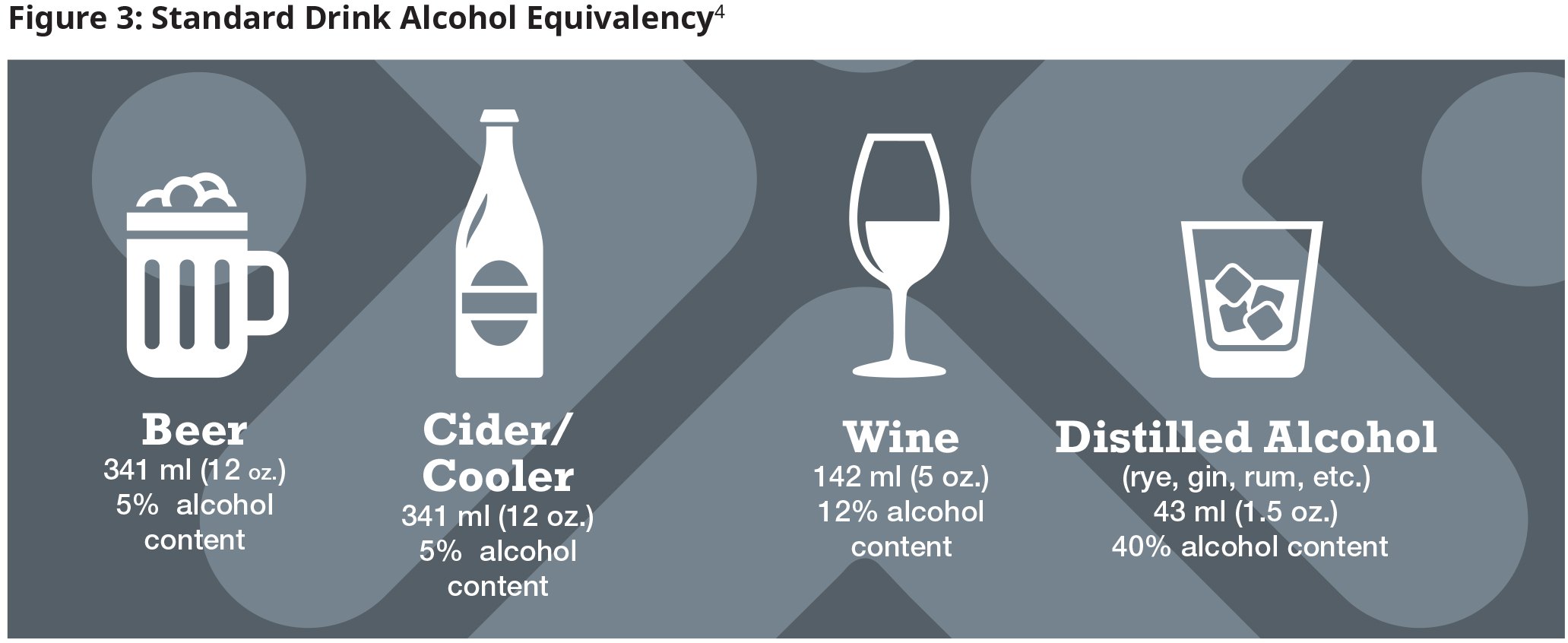

- Primary care practitioners can adjust recommendations based on individual patient factors, including mass, biological (sex-related) factors (e.g., alcohol pharmacokinetics, hormone levels), and psycho-socio-cultural (gender-related) factors.3

Epidemiology

AUD and HRD are common in Canada.4 It is estimated that up to 18% of all Canadians aged 15 or older have met the clinical criteria for an AUD during their lifetime.5 19.5% of Canadians aged 12 or older currently drink more than recommended daily or weekly limits.6 Nearly 200 disease or injury conditions are wholly or partly attributable to alcohol use. The total global burden of disease is estimated to be two to three times higher than that of all illicit substances combined.7, 8 In BC, there were nearly 28 alcohol-related deaths per 100,000 people in 2017.9 In the context of the opioid overdose crisis, which claimed approximately 31 lives per 100,000 people in BC in 2018, alcohol was present in over 25% of overdose deaths between 2016 and 2018.10

In BC, annual per capita consumption rates of pure ethanol have increased,9 an upward trend that has been correlated with the privatization of alcohol sales and increased availability of and access to alcohol.11 Hospitalization rates in BC for alcohol-related conditions increased, surpassing those for tobacco-related conditions in 2017.9 Similarly, the number of primary care visits for alcohol-related conditions increased by 53% between 2001 and 2011.12 Excessive alcohol consumption may also result in multiple psychosocial and relational harms, including absenteeism, family disruption, violence, and lost income.13 Refer to the Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms (CSUCH) Visualization Tool.

The prevalence of alcohol-related harms is higher for the following patient populations: Indigenous peoples, 2SLGBTQ+ populations, pregnant individuals, youth, older adults (age > 64 ), and individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders. The reason for increased harms in some patient populations is complex, impacted by factors including but not limited to history of colonization, inter-generational trauma, and ongoing discrimination. Drinking is a leading cause of death and social issues in young people. Binge drinking is common in youth, and intoxication is associated with high risks of injuries, aggression and violence, dating violence, and worsening academic performance. Youth under the legal drinking age should delay drinking for as long as possible.14

Risk Factors

It is common for alcohol use to coincide with other substance use. For people with AUD, tobacco use disorder is the most commonly reported co-occurring substance use disorder, resulting in various adverse health effects (e.g., cognitive impairment and increased risk of cirrhosis). There is an increased risk of respiratory depression, overdose, and death for those who use opioids and alcohol concurrently, or benzodiazepine receptor agonists and alcohol. See the BCCSU Provincial Guideline for the Clinical Management of High-Risk Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder (2019) for more information.

Drinking alcohol can cause several types of cancer.15,16 The US Department of Health and Human Services’ Report on Carcinogens, the National Toxicology Program lists consumption of alcoholic beverages as a known human carcinogen. Current evidence indicates that the more alcohol a person drinks, the higher their risk of developing certain cancers linked to alcohol use. This correlation is particularly prevalent the more alcohol a person drinks regularly over time. Even those without an AUD but who have one drink per day or are binge drinkers (i.e., those who consume 4 or more drinks for women and 5 or more drinks for men in one sitting) have a modestly increased risk of some cancers.17, 21 Based on data from 2009, an estimated 3.5% of cancer deaths in the United States (about 19,500 deaths) were alcohol-related.22, 23

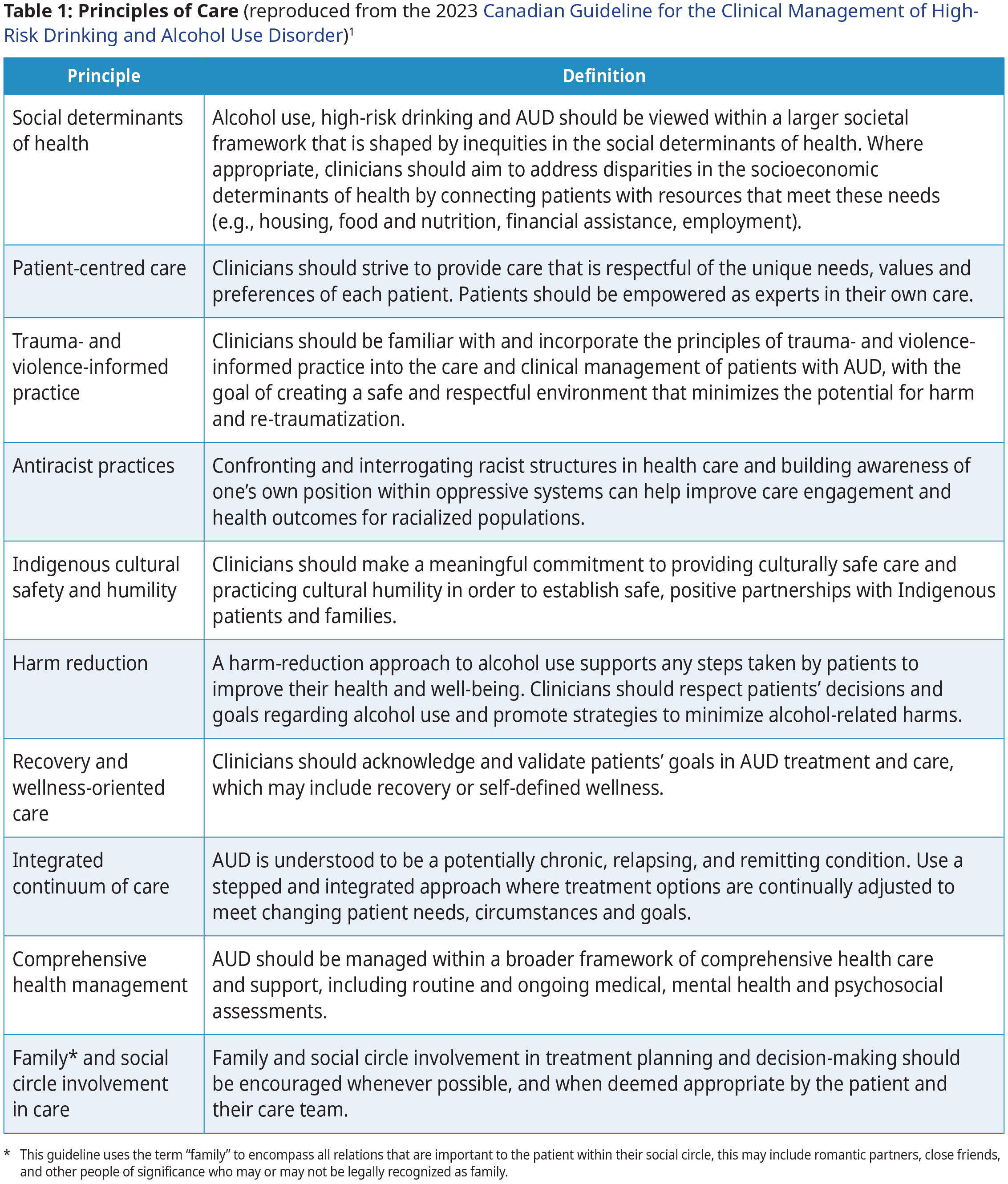

Principles of Care

Primary care providers play an important role in early detection and intervention for HRD, outpatient withdrawal management and treatment of AUD, and connecting patients and families with specialized services and community- based supports.24 Although HRD and AUD can be quickly and easily identified using simple screening tools, alcohol use screening is not widely implemented in clinical practice.25 This is a critical missed opportunity for early intervention, at a point where many individuals, including adolescents and young adults, may respond positively to brief counselling interventions alone.25 Screening and initial intervention are well within the scope of practice for all primary care practitioners.

Several overarching principles of care apply to all recommendations and to establishing positive partnerships with patients and families experiencing alcohol-related harms. See Table 1: Principles of Care.

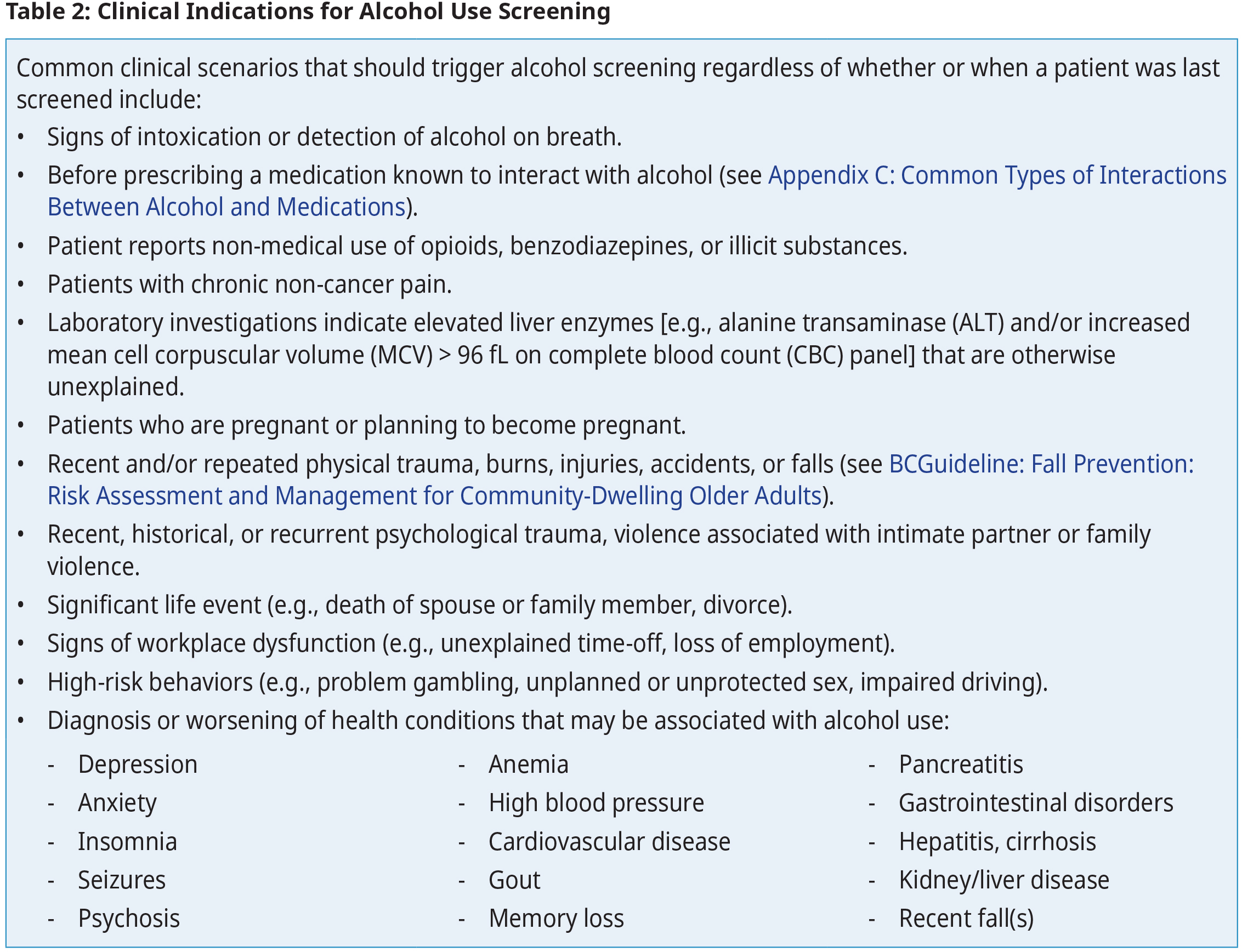

Alcohol Use Screening

- Brief interventions for drinking above low-risk alcohol limits

Recommendation 1: Screen all patients routinely for alcohol use above low-risk limits.

Recommendation 2: Screen youth patients for alcohol use with Associated Document: Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble (CRAFFT) instrument or U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Screening Tool.

Recommendation 3: Awareness of Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health

Offer education regarding alcohol use to patients as appropriate. Patients may benefit from receiving education about Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health. Many individuals look to their care providers as the primary source of this education.

Remarks

- This recommendation is graded as strong despite limited research evidence. It is the consensus of the committee that all patients could potentially benefit from increased knowledge and awareness of Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health.

- Cultural safety and humility are critical when speaking with Indigenous patients and families about alcohol use. Some patients may have experienced stigma and discrimination or have been subject to harmful stereotypes about Indigenous peoples and alcohol in the past. Using culturally safe approaches can minimize unintended harms and strengthen the therapeutic relationship.

- Primary care practitioners who demonstrate that they are comfortable and willing to acknowledge difficult topics, and believe in their patient’s ability to make positive changes are better able to support their patients improve their well-being, address past experiences, and give hope for the future.26 Refer to Associated Document: Validating and Invalidating Statements and Curious Questions.

Individuals sometimes underreport alcohol use due to experiences of guilt or a fear of facing judgment. By using a trauma-informed motivational interviewing approach, clinicians can still have valuable conversations about alcohol use. There are multiple screening tools available to practitioners, including:

- Screening Adult Patients: Single Alcohol Screening Question (SASQ), AUDIT, AUDIT-Consumption (AUDIT-C), Cut- down, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye Opener (CAGE) questionnaire. (see Associated Document)

- Screening persons with substance use disorders (SUD) or those whose use is at higher levels of risk: Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT)

- Screening Pregnant Patients: Single Alcohol Screening Question (SASQ)

- Note that the BC Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health also has several guides to support clinicians in engaging with pregnant individuals and their partners on alcohol use.

- Refer to Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report to see specific messages for girls and women.

Screening Youth

For youth aged 10–18, the following validated screening tools are available: AUDIT, AUDIT-Consumption (AUDIT-C), and the six-question Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble (CRAFFT) instrument (which is specifically for screening adolescents).4 However, a simplified 1-2-question screening approach may be preferred due to brevity and ease of recall in primary care settings. Also consider using the NIAAA Screening Tool. Early identification can lead to more youth accessing appropriate intervention choices.27 It is imperative for safe spaces to be created to facilitate nuanced conversations with youth patients.

Cultural safety and humility are critical when talking to Indigenous patients and families about alcohol use. Many patients may have experienced stigma and discrimination or been subject to harmful stereotypes about Indigenous peoples and alcohol or have heard stories of their friends and family experiencing these harms from the health care system. Clinicians can engage in their own life learning practice of cultural safety and humility which can support strengthening the therapeutic relationships with Indigenous patients and mitigate potential harms.

Diagnosis of AUD

AUD diagnosis is made using the DSM-5-TR Diagnostic Criteria for AUD. See algorithm in the Figure 1: Quick Guide to Outpatient Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder for more information on conducting a substance use history, physical examination and appropriate investigations.

Recommendation 4: Assess patients who screen positive for high risk alcohol use or for AUD (DSM-5- TR).

DSM-5-TR AUD Criteria:1

|

A problematic sequence of alcohol use resulting in clinically significant distress/ impairment is present by a minimum of two or more of the following:

Mild: 2–3 |

Management

- Setting patient-centered treatment goals

- Patients benefit from knowing about the health and social risks of excessive alcohol use and often look to their care providers for this information.

- Adopt an approach that supports individual patient autonomy in identifying their own goals of care, which may include safer alcohol consumption, reduced alcohol consumption or abstinence. Alongside models that focus on abstinence, models that focus on a reduction in drinking and alcohol-related harms are a useful and appropriate goal for some patients. This patient-centered approach may also support continued engagement in care in a disease that can be chronic and relapsing.

- Recognize that a reduction in drinking and alcohol-related harms is a useful and important goal for some patients.

Recommendation 5: Brief Intervention for Drinking Alcohol Above Low-Risk Limits

Use brief interventions in all patients who consume moderate or high amounts of alcohol but who do not meet criteria for AUD.

Remarks

- Brief intervention with frequent reassessment/check-in to keep conversations going is the recommended intervention for alcohol use in patients who DO NOT meet an AUD diagnosis; for individuals who do meet an AUD diagnosis, see recommendation 6.

Recommendation 6: Primary Care-led Psychosocial Treatment Interventions for AUD

Consider using a motivational interviewing-based approach when counselling patients with mild to severe AUD to support achievement of treatment goals. Refer to the Centre for Collaboration, Motivation and Innovation for additional information.

- Overview of alcohol withdrawal

≥ 70% of patients in outpatient withdrawal management complete treatment, and 50% of these patients stay involved in ongoing addiction care to achieve long-term recovery goals (i.e., reducing heavy drinking or abstinence).28

- Assessing risk of severe complications of alcohol withdrawal

Recommendation 7: Assessing the Risk of Severe Complications of Withdrawal

Use PAWSS to help select the most appropriate withdrawal management pathway. PAWSS is a validated tool to assess the risk of severe complications of alcohol withdrawal in patients with AUD. For more information see Associated Document: Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS).

Remarks

- This tool should be used in conjunction with clinical judgement based on a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s medical history, current circumstances, needs, and preferences.

- The PAWSS is not suitable for self-assessment and should be administered by a clinician.

- The PAWSS has not been validated in pregnant or youth populations.

- Patients may confuse some PAWSS criteria with common and less severe symptoms of withdrawal (e.g., seizures and delirium tremens). To avoid false positives, the administering clinician should clearly define these criteria prior to obtaining the patient’s responses.

- Point-of-care assessment of withdrawal symptom severity

Periodic assessment of the withdrawal process has been shown to facilitate appropriate adjustments in dosing and mitigate the risk of progressive severity in patients deemed high-risk for severe or complicated withdrawal (e.g., PAWSS ≥ 4). There are many alcohol withdrawal complications, including seizures and delirium.29–31 The most commonly used alcohol withdrawal symptom severity assessment scales are the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment Alcohol revised (CIWA-Ar) (see Associated Document: Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised (CIWA-Ar)).31–3

Withdrawal Management in Adolescent Patients

An estimated 5-10% of adolescents with an AUD will experience withdrawal symptoms,34 with only a subset requiring pharmacological management.35 Due to the relative rarity of this condition, no empirical data are available to make evidence-based recommendations for the pharmacological management of alcohol withdrawal in adolescents. When pharmacological management is necessary, approaches are generally the same for adolescents as for adult patients.35 Consultation with an addiction medicine specialist is strongly recommended before initiating monitored withdrawal in an outpatient setting, even if the PAWSS < 4, as this instrument has not been validated for use in youth. All care providers, patients, and families in BC can access information and referrals from the D-Talks (youth detox) provincial contact line (1-866-889-4700) and online at http://www.bcdetox.com/sample-page-2.

Withdrawal Management in Pregnant Patients

There are unique considerations for withdrawal management in pregnant individuals. The potential maternal and fetal risks and benefits of pharmacotherapy must be weighed against the known risks of untreated withdrawal and/ or continued alcohol consumption. Very few medications have been studied in pregnant individuals. Several options that have been proven safe and effective in non-pregnant patients are contraindicated in pregnancy due to the risk of fetal malformations (e.g., carbamazepine).

The limited research on withdrawal management during pregnancy has focused almost exclusively on benzodiazepine-based pharmacotherapy and has yielded conflicting results. Early studies suggested that benzodiazepines are associated with increased risk of fetal malformations. However, a more recent meta-analysis concluded that, overall, the available evidence did not support their teratogenicity.36–38 Caution is indicated as very few studies have been published on the topic.

Few clinical practice guidelines have made explicit recommendations for withdrawal management in pregnant individuals. The World Health Organization’s 2014 Guidelines for Identification and Management of Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders in Pregnancy recommend that pregnant individuals with AUD are admitted to inpatient withdrawal management facilities or hospital settings that are appropriately equipped to monitor fetal movement and vital signs during treatment.39 Pharmacotherapy with benzodiazepines is recommended where indicated and delivered under close observation so that dose can be titrated to severity of withdrawal symptoms.39,40 In the absence of clear evidence, the risks of untreated maternal alcohol withdrawal symptoms, including fetal distress, spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, and fetal demise,38 must be weighed against the risks of pharmacological treatment.

Withdrawal Management in Older Adults

Individuals aged ≥65 are more vulnerable to the effects and harms of alcohol. Aging has many dimensions, and guidance may be relevant for some individuals < 65 years of age due to medical, psychological, and social contexts. On the other hand, some individuals ≥ 65 years of age may be better suited to approaches used for adults < 65 years of age. Due to stigma, fear of judgement, and cognitive deficits, under-reporting substance use may occur. Be mindful of the clinical signs of alcohol-related problems, and approach screening of older adults with patience and sensitivity. Older adults experience an increased prevalence of comorbid medical conditions and a higher susceptibility to severe alcohol withdrawal complications. As a result, a higher intensity, structured approach to care, e.g., referrals to inpatient withdrawal management, inpatient treatment programs, or intensive outpatient programs may benefit individuals aged ≥ 65.28

Moreover, the effect on comorbid conditions and potential drug-drug interactions should be carefully examined when selecting AUD pharmacotherapies, since older patients likely have a higher prevalence of medical conditions and/or take various medications for chronic disease management.28 Review the social supports and functional status of elderly patients with AUD, in addition to their medical and psychiatric comorbidities. Interdisciplinary care for these patients is important; consult addiction services where available. For more information refer to the 2019 Canadian Guidelines on Alcohol Use Disorder Among Older Adults by the Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health.

- Pharmacotherapies for Withdrawal Management

See Figure 1: Quick Guide to Outpatient Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder.

Recommendation 8: Pharmacotherapy for Management of Mild to Moderate Withdrawal in Patients at Low Risk of Severe Complication

For patients at low risk of severe complications of alcohol withdrawal (i.e., PAWSS < 4), consider prescribing alternatives to benzodiazepines, e.g., gabapentin, carbamazepine, and adjuvants such as clonidine for withdrawal management in an outpatient setting.

Remarks

- Selection of an appropriate medication should be made through shared decision-making by patient and provider, especially in consideration of a patient’s goals, needs, preferences, and ability to adhere.

- Benzodiazepines are not a preferred option for outpatient withdrawal management due to their side effects, tendency to potentiate the effects of alcohol when used concurrently, and potential for non-medical use. Although not preferred, if benzodiazepines are prescribed for outpatient withdrawal management, the following measures may be considered:

- Prescribing a short course prescription (3–7 days) with a fixed-dose schedule.

- Daily dispensing from a pharmacy.

- Frequent clinical visits to closely monitor side effects, symptoms, and alcohol use, and to make dose adjustments as needed.

- People of Asian descent are at increased risk of serious cutaneous adverse drug reactions [e.g., Stevens- Johnson Syndrome, Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN), maculopapular rash] due to a higher baseline prevalence of the HLA-B*1502 allele, a marker for carbamazepine toxicity. Avoid carbamazepine in this population unless genetic testing is available and has excluded risk.41

- In addition to a PAWSS score < 4, candidates for outpatient withdrawal management should meet the following criteria. Patients who do not meet these criteria should be referred to inpatient treatment:

- No contraindications such as severe or uncontrolled comorbid medical conditions (e.g., acute confusion, gastrointestinal bleeding, electrolyte imbalance, infection, cognitive impairment, chronic and complex pain disorders), serious and unstable psychiatric conditions, history of documented seizure disorder concurrent severe substance use disorders other than tobacco use, pregnancy, old age or physical frailty, and/or social instability.

- Ability to commit to daily medical visits for the first 3 -5 days, or to participate in an appropriate remote mode of medical follow-up when in-person visits are not feasible.

- Ability to take oral medications.

- Stable accommodation and reliable caregiver for support and symptom monitoring during acute withdrawal period (i.e., 3-5 days).

- See Appendix A: Pharmacotherapy Options for Outpatient Management of Alcohol Withdrawal for more information.

Recommendation 9: Withdrawal Management for Patients at High Risk of Severe Complications

For patients at high risk of severe complications of withdrawal (e.g., PAWSS ≥ 4), clinicians should offer a short- term benzodiazepine prescription. This is ideally completed in an inpatient setting. Where inpatient admission is not available, benzodiazepine medications can be offered to patients in outpatient settings if they can be closely monitored and supported.

Remarks

- Conditions that could indicate inpatient withdrawal management regardless of PAWSS score include:

- Multiple unsuccessful attempts at outpatient withdrawal management

- Failure to respond to medications after 24-48 hours

- Unstable medical conditions

- Unstable psychiatric disorders

- Chronic, complex pain disorders

- Concurrent use of other CNS depressants (e.g., prescribed or nonmedical use of Z-drugs, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, opioids)

- Severe liver compromise (e.g., jaundice, ascites, decompensated cirrhosis)

- Pregnancy

- Lack of a safe, stable, and substance-free setting and /or caregiver to dispense medication

- If a patient has a PAWSS ≥ 4 but inpatient treatment is not feasible due to patient preference or access to beds, and a clinical decision to prescribe benzodiazepines is made, develop a care plan that optimizes connection with a community pharmacist, consider involving family members or other supports and monitor patient closely (e.g., daily phone calls, frequent clinical visits).

- Provide education regarding risks of concurrent benzodiazepine and alcohol use. Ensure the patient is aware of symptoms that require management in an inpatient setting.

- Continuity of care following withdrawal management

Recommendation 10: Benzodiazepines should not be prescribed as ongoing treatment for AUD.

Recommendation 11: Where possible and when appropriate, patients who complete withdrawal management should be offered continuing care. Withdrawal management is a short-term intervention that does not resolve underlying medical, psychological, or social issues associated to AUD, and should be considered a bridge to continuing care, treatment, and support that will address these concerns.

Recommendation 12: Patients should not be prescribed antipsychotics or SSRI antidepressants if the primary reason is for the treatment of AUD.

- If SSRI antidepressants are prescribed for individuals with co-occurring mood disorder, clinicians and patients should be alert to the risk of increased alcohol cravings and use with SSRI therapy and discontinue as appropriate.42

- Patients with AUD are often prescribed modern antidepressants and/or antipsychotics to treat AUD symptoms, but these medications have little benefit in AUD and may worsen AUD outcomes.

Pharmacological Management

Recommendation 13: First-line Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Use Disorder

Consider offering naltrexone or acamprosate to adult patients with moderate to severe AUD. These are first-line pharmacotherapy agents that may support patient-identified treatment goals.

- Naltrexone is recommended for patients who have a treatment goal of either abstinence or a reduction in alcohol consumption.

- Acamprosate is recommended for patients who have a treatment goal of abstinence.

Remarks

- Naltrexone is contraindicated in patients regularly taking opioids/those with opioid dependence, as it will initiate precipitated withdrawal in individuals who have not ceased opioid use for 7–10 days. Caution is advised in prescribing naltrexone to patients with renal and liver disease, patients who are pregnant, and patients under the age of 18, and patients over the age of 65.*Ф

- Acamprosate is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (i.e., creatinine clearance ≤ 30mL/min), patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or its constituents, and in patients who are breastfeeding.

- Completion of withdrawal management is not a mandatory prerequisite to starting treatment

* Naltrexone may have a protective effect against overdose for individuals who regularly use alcohol and infrequently use opioids and may reduce opioid use.43

Ф Naltrexone should not be prescribed to patients who are taking opioids, either prescribed or illicit. This includes opioids prescribed for opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder (e.g., buprenorphine/naloxone, methadone, slow-release oral morphine). Prescribing naltrexone to an individual taking opioids increases the risk of precipitated withdrawal or potentially fatal overdose if opioids are consumed in an effort to overcome naltrexone’s opiate blockade. The safety and efficacy of combination naltrexone and disulfiram is unknown. The combined use of two potentially hepatotoxic medications is not recommended unless the benefits outweigh the risks.

- Duration of treatment

-

AUD is a chronic, relapsing, and remitting medical condition, therefore, an ongoing and individually tailored approach to clinical management is required.

-

Most clinical practice guidelines recommend that AUD pharmacotherapy be prescribed for at least 6 months, at which point the utility of continuing treatment can be re-assessed in collaboration with the patient.40, 44, 45

-

If deemed clinically necessary, medications can be continued indefinitely unless safety concerns arise.46 For additional details, please refer to tables available at BCCSU guidelines.

-

Patients may also choose to restart medications while still abstinent if they are experiencing cravings or triggers to return to alcohol use.

-

-

-

Alternative and emerging pharmacotherapies for AUD

Recommendation 14: Alternative Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Use Disorder

Consider offering topiramate or gabapentin to adult patients with moderate to severe AUD who do not benefit from, have contraindications to first-line medications, or express a preference for an agent.

Remarks

- Selection of an appropriate medication should be made through a shared decision-making process between patient and provider after reviewing evidence of benefits and risks, and especially in the context of the patient’s goals, needs and preferences.

- Contraindications, side effects, feasibility (dosing schedules, out-of-pocket costs), and patient history with either medication should be taken into account.

- As with any medication prescribed off-label, it is important to conduct a full assessment, including careful review of concomitant medications for potential drug-drug interactions, and to clearly document patient consent prior to initiating treatment.

- Gabapentin is contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or its constituents. Caution is advised in prescribing gabapentin to patients with cognitive or mental impairment, taking opioids (prescribed or non-medical use), who are pregnant or breastfeeding, are under the age of 18, and over the age of 65.

- Topiramate is contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or its constituents and in patients who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant. Caution is advised in prescribing topiramate to patients with renal disease or failure, with hepatic disease, under the age of 18, and over the age of 65. Due to dose-dependent risk of significant CNS side effects, gradually titrate dose upwards over a period of 4-8 weeks.

Pharmacotherapy options for youth

- Pharmacotherapies approved for treatment of AUD in adults (naltrexone, acamprosate) can be considered on a case-by-case basis for treatment of moderate to severe alcohol use disorder in youth (e.g., ages 10 and older).40, 47 – 51

- Alcohol is the most commonly used substance in youth, which does warrant routine screening, brief intervention, and advice on safer use. However, very few youths seen in primary care will meet the DSM-5-TR criteria for a moderate to severe alcohol use disorder.

- Consultation with an addiction medicine specialist, the RACE line (Vancouver area: 604-696-2131; toll-free: 1-877-696-2131, www.raceconnect.ca) or the 24/7 Addiction Medicine Clinician Support Line to speak to an Addiction Medicine Specialist at 778-945-7619 is recommended prior to prescribing AUD pharmacotherapy to youth.

Pharmacotherapy options for pregnant patients

- Prescribing AUD pharmacotherapy to pregnant patients should be done in close consultation with a perinatal addiction medicine specialist (Local RACE Line Number: 604-696-2131 or Toll free number: 1-877-696-2131 – Press 3).

- Topiramate is contraindicated in patients who are pregnant or plan to become pregnant due to its association with cleft palate if used in the first trimester.52 There is strong recommendation against the use of disulfiram in pregnancy, due to the potential risks of a severe disulfiram- alcohol reaction to the fetus.38

- As there is insufficient evidence to support use of baclofen and ondansetron in non-pregnant patients, neither medication is considered appropriate for use in pregnancy. Refer to Fischler et al. (2022) for off-label and investigational drugs for AUD treatment.

Ongoing Care – Psychosocial treatment interventions

Recommendation 15: Specialist-led Psychosocial Treatment Interventions for AUD

Consider providing all patients with AUD information about and referrals to specialist-led psychosocial treatment interventions. See the resource section for referral information.

Remarks

- The referring clinician should continue to play an active role after connecting individuals to psychosocial treatment interventions by checking in with patients on their experience and overall satisfaction, encouraging regular attendance, and including related patient- or program-defined goals in their treatment plan.

- Referring clinicians should attempt to establish regular communication with specialist providers and programs to facilitate continuity of care, transitions in care, and to share relevant information (with the patient’s permission, e.g., assessments, progress notes, discharge summaries).

- Combining pharmacotherapy and psychosocial treatment interventions

- Use a stepped and integrated care approach, where treatment type and intensity are continually adjusted to match the individual patient’s needs and circumstances over time. All therapeutic interventions should be understood as a trial of therapy and reassessed on a regular basis.

- A stepped strategy recognizes that many individuals may benefit from the ability to access different psychosocial treatment and recovery support options at different times in their recovery.

- The stepped approach may include treatment intensification (e.g., adding specialized psychosocial treatment to a pharmacotherapy-based strategy, consideration of structured treatment programs), transitions between different treatment options, and strategies to de-intensify pharmacological or psychosocial treatment at the patient’s discretion, where the patient can opt to re-initiate pharmacotherapy or psychosocial treatment at any time if needs and circumstances change.

Recommendation 16: Peer-based Support Groups for Individuals with AUD

Consider providing all patients with AUD information about and referrals to peer-support services, harm reduction interventions and/or other services in the community (as appropriate/per patient goals).

Remarks

- Recommend providers are aware of and make informed referrals to peer-support groups that are active locally and online, including groups for specific populations (e.g., men, women, 2SLGBTQ+, co-occurring disorders, etc.), age-appropriate options for youth, and services for families.

- The primary care clinician or care team are encouraged to continue to play an active role after connecting individuals to peer support groups by checking in on their experiences and overall satisfaction, encouraging regular attendance, and including related patient or program-defined goals in the patient’s treatment plan. Note that some groups focus on abstinence, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (A.A.), others on harm reduction. The patient’s preferences’ need to be matched to the group’s goals. Encourage an individual to explore several options, understanding that some will be a better fit.

- Peer support groups

- Self-Management and Recovery Training© (SMART© Recovery) – Offers mutual support meetings where participants design and implement their own recovery plan to create a more balanced, purposeful, fulfilling, and meaningful life. SMART provides specialized meetings and resources for a variety of communities. It is a method of moving from addictive substances and associated behaviors to a life of positive self-regard and willingness to change.

- Alcoholics Anonymous (A.A.) and 12-Step Programs – A fellowship of people who come together to solve their drinking problem. The primary purpose is to help individuals to achieve and maintain sobriety. Open meetings are available to anyone interested in A.A.’s program of recovery from alcohol use disorder. Non-drinkers may attend open meetings as observers. Closed meetings are for A.A. members only or for those who have a drinking problem and have a desire to stop drinking.

- LifeRing – Provides access to community-based mutual self-help support groups for those who self-identify with problematic substance use.

- Community-based treatment and recovery programs

- Intensive Outpatient Programs

- Inpatient Treatment Programs

- Supportive Recovery Housing

- Employer supported programs

- Psychosocial support services

- There is likely a benefit to AUD care being offered in the context of interdisciplinary primary care teams that are equipped to address these needs when possible.

- Where patients have encountered barriers to engagement in care, intensive case management,53, 54 assertive community outreach teams,54 – 56 and peer-based outreach and support services57, 58 may also be effective strategies to improve retention in treatment.

- Managed alcohol programs (MAP)

MAPs are a harm reduction strategy used to minimize the personal harm and adverse societal effects of severe AUD, particularly as experienced by individuals who may be homeless or unstably housed.59,60 Refer to the Provincial Guideline for the Clinical Management of High-Risk Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder (2019) and Managed Alcohol Programs – Canadian Operational Guidance Document (2023) for more information.

- Controversies in Care

The recommendation for screening youth is based on known risks and harms of high-risk drinking and AUD, the benefits of early identification, intervention, and treatment, and the accuracy of youth-specific screening tools (e.g., NIAAA Screening Tool) for predicting current or future alcohol-related problems in youth.

While further research is needed on the balance of benefits and harms of screening and brief intervention for youth, screening and brief intervention are cost-effective and non-invasive interventions that address the preventable burden of alcohol use and high-risk drinking among youth. Screening and brief intervention for youth is in line with recommendations of the American Academy of Pediatrics and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Resources

Abbreviations:

AUD

CIWA-Ar

HRD

MAP

PAWSS

SASQ

SBIRT

SUD

Alcohol use disorder

Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised

High-risk drinking

Managed alcohol programs

Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale

Single Alcohol Screening Question

Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment

Substance use disorder

Diagnostic Codes

303: Alcohol dependence syndrome

305: Non dependent use of drugs

Appendices

- Appendix A: Pharmacotherapy Options for Outpatient Management of Alcohol Withdrawal

- Appendix B: Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Use Disorder

- Appendix C: Common Types of Interactions Between Alcohol and Medications

Associated Documents

The following documents accompany this guideline:

- Full Guideline

- One-Page Summary

- Quick Guide to Outpatient Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder

- Practitioner Support

- AUD Questionnaires

- Quality Improvement

- BCGuideline: Fall Prevention: Risk Assessment and Management for Community-Dwelling Older Adults

- List of Contributors

References

- Wood E, Bright J, Hsu K, Goel N, Ross JWG, Hanson A, et al. Canadian guideline for the clinical management of high-risk drinking and alcohol use disorder. Can Med Assoc J. 2023 Oct 16;195(40):E1364–79.

- In: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Understanding Alcohol Use Disorder [Internet] National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/understanding-alcohol-use-disorder

- Erol A, Karpyak VM. Sex and gender-related differences in alcohol use and its consequences: Contemporary knowledge and future research considerations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;(v;156:1–13).

- Butt P. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Alcohol and health in Canada: a summary of evidence and guidelines for low-risk drinking [Internet [Internet]. Ottawa, Ont: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse; 2012. Available from: https://www.deslibris.ca/ID/233659

- CANSIM SC. 82-624-X — Table 1 — Rates of selected mental or substance use disorders, lifetime and 12 month, Canada, household 15 and older [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-624-x/2013001/article/tbl/tbl1-eng.htm

- Canada S. Table 13-10-0096-11 — Heavy drinking, by age group, 2016 and 2017 [Internet [Internet]. Statistics Canada; 2019. Available from: https://www150. statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310009611

- Rehm J, Baliunas D, Brochu S, Fischer B, Gnam W, Patra J. The costs of substance abuse in Canada 2002 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/ eprint/95508

- Organization WH. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018 [Internet [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. p. 450. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274603

- University of Victoria, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research. British Columbia Alcohol and Other Drug Monitoring Project: substance related hospitalizations and deaths [Internet [Internet]. University of Victoria; 2022. Available from: https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/cisur/stats/

- Justice BCM, Service BCC. Illicit Drug Overdose Deaths in BC: January 1, 2008 – December 31, 2018 [Internet]. Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/ birth-adoption-death-marriageand-

- Stockwell T, Zhao J, Macdonald S, Pakula B, Gruenewald P, Holder H. Changes in per capita alcohol sales during the partial privatization of British Columbia’s retail alcohol monopoly 2003-2008: a multi-level local area analysis. Addiction. 2009;(v;104(11):1827–36).

- Slaunwhite AK, Macdonald S. Primary health care utilization for alcohol-attributed diseases in British Columbia Canada 2001–2011. BMC Fam Pr. 2015;Dec;16(1):34.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Alcohol Harm in Canada: Examining Hospitalizations Entirely Caused by Alcohol and Strategies to Reduce Alcohol Harm [Internet]. Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2017. Available from: http://proxy.library.carleton.ca/loginurl=https://www.

- Paradis C, Butt P, Shield K, Poole N, Wells S, Naimi T, et al. Canada’s guidance on alcohol and health: final report [Internet]. Ottawa, Ont.: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction; 2023. Available from: https://www.ccsa.ca/canadas-guidance-alcohol-and-health

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer. Lyon, France : Geneva: International Agency for Research on Cancer ; Distributed by WHO Press; 2010. p. 1424.

- World Health Organization, editor. International Agency for Research on Cancer [Internet]. Lyon; Available from: https://www.iarc.who.int/fr/risk-factor/alcohol-fr/

- Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, Tramacere I, Islami F, Fedirko V. Light alcohol drinking and cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;Feb;24(2):301–8.

- Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, Tramacere I, Islami F, Fedirko V. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose–response meta- analysis. Br J Cancer. 2015;Feb;112(3):580–93.

- Cao Y, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL. Light to moderate intake of alcohol, drinking patterns, and risk of cancer: results from two prospective US cohort studies. BMJ. 2015 Aug 18;

- Chen WY, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Moderate Alcohol Consumption During Adult Life, Drinking Patterns, and Breast Cancer Risk. JAMA. 2011 Nov;2;306(17):1884.

- White AJ, DeRoo LA, Weinberg CR, Sandler DP. Lifetime Alcohol Intake, Binge Drinking Behaviors, and Breast Cancer Risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2017 Sep;1;186(5):541–9.

- Nelson DE, Jarman DW, Rehm J, Greenfield TK, Rey G, Kerr WC. Alcohol-Attributable Cancer Deaths and Years of Potential Life Lost in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2013;Apr;103(4):641–8.

- Institute NC. Alcohol and Cancer Risk [Internet [Internet]. National Cancer Institute; 2021. p. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-

- Spithoff S, Kahan M. Primary care management of alcohol use disorder and at-risk drinking: Part 2: counsel, prescribe, connect. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. Vol. Jun;61(6):515–21. 2015.

- Force USPST, SJ C, AH K, DK O, MJ B, AB C. Screening and Behavioral Counseling Interventions to Reduce Unhealthy Alcohol Use in Adolescents and Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018 Nov. 13;320(18):1899.

- Oregon Pain Guidance. The Art of Difficult Conversations [Internet]. Oregon Pain Guidance; Available from: https://www.oregonpainguidance.org/guideline/the- art-of-difficult-conversations/

- Meca A, Tubman JG, Regan T, Zheng DD, Moise R, Lee TK. Preliminary Evaluation of the NIAAA/AAP Brief Alcohol Use Screener. Alcohol Alcohol. 2017 May;1;52(3):328–34.

- British Columbia Centre on Substance Use (BCCSU). Provincial Guideline for the Clinical Management of High-Risk Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder [Internet [Internet]. Available from: https://www.bccsu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/AUD-Guideline.pdf

- Young GP, Rores C, Murphy C, Dailey RH. Intravenous phenobarbital for alcohol withdrawal and convulsions. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;Aug;16(8):847–50.

- Naranjo CA, Sellers EM, Chater K, Iversen P, Roach C, Sykora K. Nonpharmacologic intervention in acute alcohol withdrawal. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;Aug;34(2):214–9.

- McKay A, Koranda A, Axen D. Using a symptom-triggered approach to manage patients in acute alcohol withdrawal. Medsurg Nurs J Acad Med-Surg Nurses. 2004;Feb;13(1):15–20, 31:21.

- Maldonado S JR, Y A, JF HE, K S, H L, S. The “Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale” (PAWSS): Systematic literature review and pilot study of a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol. 2014;Jun;48(4):375–90.

- Elholm B, Larsen K, Hornnes N, Zierau F, Becker U. Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome: Symptom-Triggered versus Fixed-Schedule Treatment in an Outpatient Setting. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011 May;1;46(3):318–23.

- Chung T, Martin CS, Armstrong TD, Labouvie EW. Prevalence of DSM-IV Alcohol Diagnoses and Symptoms in Adolescent Community and Clinical Samples. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;May;41(5):546–54.

- Clark DB. Pharmacotherapy for Adolescent Alcohol Use Disorder: CNS Drugs. Vol. Jul;26(7):559–69. 2012.

- Enato E, Moretti M, Koren G. Motherisk Rounds: The Fetal Safety of Benzodiazepines: An Updated Meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;Jan;33(1):46–8.

- Bhat A, Hadley A. The management of alcohol withdrawal in pregnancy — case report, literature review and preliminary recommendations. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;273(e1-273.e3).

- DeVido J, Bogunovic O, Weiss RD. Alcohol Use Disorders in Pregnancy. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;Mar;23(2):112–21.

- Organization WH. Guidelines Review Committee. WHO Guidelines for the Identification and Management of Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders in Pregnancy [Internet. WHO [Internet]. 2014 Jan 26; Available from: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/pregnancy_guidelines/en/

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA. Detoxif Subst Abuse Treat Treat Improv Protoc TIP Ser [Internet]. (45). Available from: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma15-4131.pdf

- PrTEGRETOL® (carbamazepine) Product Monograph; tablets, 200 mg; chewable tablets, 100 mg and 200 mg; controlled-release tablets, 200 mg and 400 mg; suspension, 100 mg/tsp (5 mL. Submiss Control No [Internet]. 213356. Available from: https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00045114.PDF

- Gandhi P, Healy D, Bozinoff N. Severe alcohol use disorder after initiation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy. Can Med Assoc J. 2023 Oct 16;195(40):E1380–2.

- Minozzi S, Amato L, Vecchi S, Davoli M, Kirchmayer U, Verster A. Oral naltrexone maintenance treatment for opioid dependence. editor., editor. Cochrane Collab. 2011 May 2;001333 3.

- Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Department of Defense (DoD). VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of substance use disorders [Internet]. Available from: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/VADoDSUDCPGFinal1.pdf

- Reus F VI, LJ B, O E, AE H, DM HL, M. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;Jan;175(1):86–90.

- Kranzler HR, Soyka M. Diagnosis and Pharmacotherapy of Alcohol Use Disorder: A Review. JAMA 2018 Aug. 28;320(8):815.

- Melamed O. Fundamentals of Addiction: Screening [Internet]. Buckley L, editor. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH); [cited 2023 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.camh.ca/en/professionals/treating-conditions-and-disorders/fundamentals-of-addiction/f-of-addiction---screening#:~:text=All%20patients%20 aged%2010%20years,up%20with%20a%20brief%20assessment.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guidance — Alcohol Use Disorders: Diagnosis, Assessment and Management of Harmful Drinking and Alcohol Dependence [Internet [Internet]. NICE; 2011. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg115

- Rolland B, Paille F, Gillet C, Rigaud A, Moirand R, Dano C. Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Dependence: The 2015 Recommendations of the French Alcohol Society, Issued in Partnership with the European Federation of Addiction Societies. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;Jan;22(1):25–37.

- Lingford-Hughes A, Welch S, Peters L, Nutt D, Ball D, Buntwal N, et al. With expert reviewers (in alphabetical order.

- Royal College of General Practitioners, Alcohol Concern, DrugScope, Royal College of Psychiatrists, College, Centre for Quality Improvement (CCQI). Practice Standards for Young People with Substance Misuse Problems. In: Publication number CCQI 127 [Internet] CCQI [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://www. drugsandalcohol.ie/17885/2/Practice_standards_for_young_people_with_substance_misuse_problems.pdf

- Hunt S, Russell A, Smithson WH, Parsons L, Robertson I, Waddell R. Topiramate in pregnancy: Preliminary experience from the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register. Neurology. 2008 Jul;22;71(4):272–6.

- Penzenstadler L, Machado A, Thorens G, Zullino D, Khazaal Y. Effect of Case Management Interventions for Patients with Substance Use Disorders: A Systematic Review [Internet]. Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00051/full

- Simoneau H, Kamgang E, Tremblay J, Bertrand K, Brochu S, Fleury MJ. Efficacy of extensive intervention models for substance use disorders: A systematic review: Efficacy of intervention models. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018 Apr;

- Drummond C, Gilburt H, Burns T, Copello A, Crawford M, Day E. Assertive Community Treatment For People With Alcohol Dependence: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016 Dec 8;

- Passetti F, Jones G, Chawla K, Boland B, Drummond C. Pilot Study of Assertive Community Treatment Methods to Engage Alcohol-Dependent Individuals. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008 Feb;14;43(4):451–5.

- Reif S, Braude L, Lyman DR, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Ghose SS. Peer Recovery Support for Individuals With Substance Use Disorders: Assessing the Evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;Jul;65(7):853–61.

- Bassuk EL, Hanson J, Greene RN, Richard M, Laudet A. Peer-Delivered Recovery Support Services for Addictions in the United States: A Systematic Review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;63:1–9.

- Fairgrieve C, Fairbairn N, Samet JH, Nolan S. Nontraditional Alcohol and Opioid Agonist Treatment Interventions. Med Clin North Am. 2018;Jul;102(4):683–96.

- Pauly BB, Vallance K, Wettlaufer A, Chow C, Brown R, Evans J. Community managed alcohol programs in Canada: Overview of key dimensions and implementation: Community managed alcohol programs. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018 Apr 9;

|

BC Guidelines are developed for the Medical Services Commission by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, a joint committee of Government and the Doctors of BC. BC Guidelines are adopted under the Medicare Protection Act and, where relevant, the Laboratory Services Act. Disclaimer: This guideline is based on best available scientific evidence and clinical expertise as of February 21, 2024. It is not intended as a substitute for the clinical or professional judgment of a health care practitioner. |