Palliative Care for the Patient with Incurable Cancer or Advanced Disease - Part 1: Approach to Care

Effective Date: February 22nd, 2017

Palliative Care Part 2: Pain and Symptom Management

Palliative Care Part 3: Grief and Bereavement

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Definition

- Background

- Assessment

- Management

- 1. Monitor patient’s functional capacity

- 2. Coordinate care with allied health care providers

- 3. Evaluate symptom burden

- 4. Establish goals of care with patients and families

- 5. Management strategies: non-pharmacologic

- 6. Management strategies: pharmacotherapy

- 7. Referral to a specialist

- 8. Indications for referral to a tertiary palliative care unit

- 9. Ongoing care

- 10. Allied health care and referral to the local hospice palliative care program

- 11. Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD)

- 12. Actively dying: the End-of-Life Care check list

- 13. Death and bereavement

- Resources

Scope

This guideline presents palliative care assessment and management strategies for primary care practitioners caring for adult patients aged ≥ 19 years with incurable cancer and end stage chronic disease of many types, and their families.

NOTE: Care gaps have been identified at important transitions for this group of patients:

- upon receiving a diagnosis of incurable cancer;

- when discharged from active treatment to the community;

- while still ambulatory but needing pain and symptom management; and

- at the transition when End-of-Life care may be needed.

Diagnostic code: 239 (neoplasm of unspecified nature)

Palliative care planning fee code: G14063

Key Recommendations

- Identify patients who would benefit from palliative care early in the illness trajectory: a palliative approach addresses the need for pain and symptom management, as well as psychosocial and spiritual support of patients and their families, beginning in disease management through to survivorship or End-of-Life care.

- Encourage patients to have an advance care planning discussion with family and/or caregivers.

- Establish goals of care with the patient and families/caregivers.

- Before ordering investigations, ensure that the results will change management to improve quality of life and/or prognostication, consistent with the patient’s goals of care.

- Organize care coordination around key illness transitions.

Definition

The World Health Organization1 defines palliative care as an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.

Palliative care:

- provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms;

- affirms life and regards dying as a normal process;

- intends neither to hasten nor postpone death;

- integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient;

- offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death;

- offers a support system to help the family cope during the patient’s illness and in their own bereavement;

- uses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families, including bereavement counselling, if indicated;

- will enhance quality of life, and may also positively influence the course of illness; and

- is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and includes those investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications.

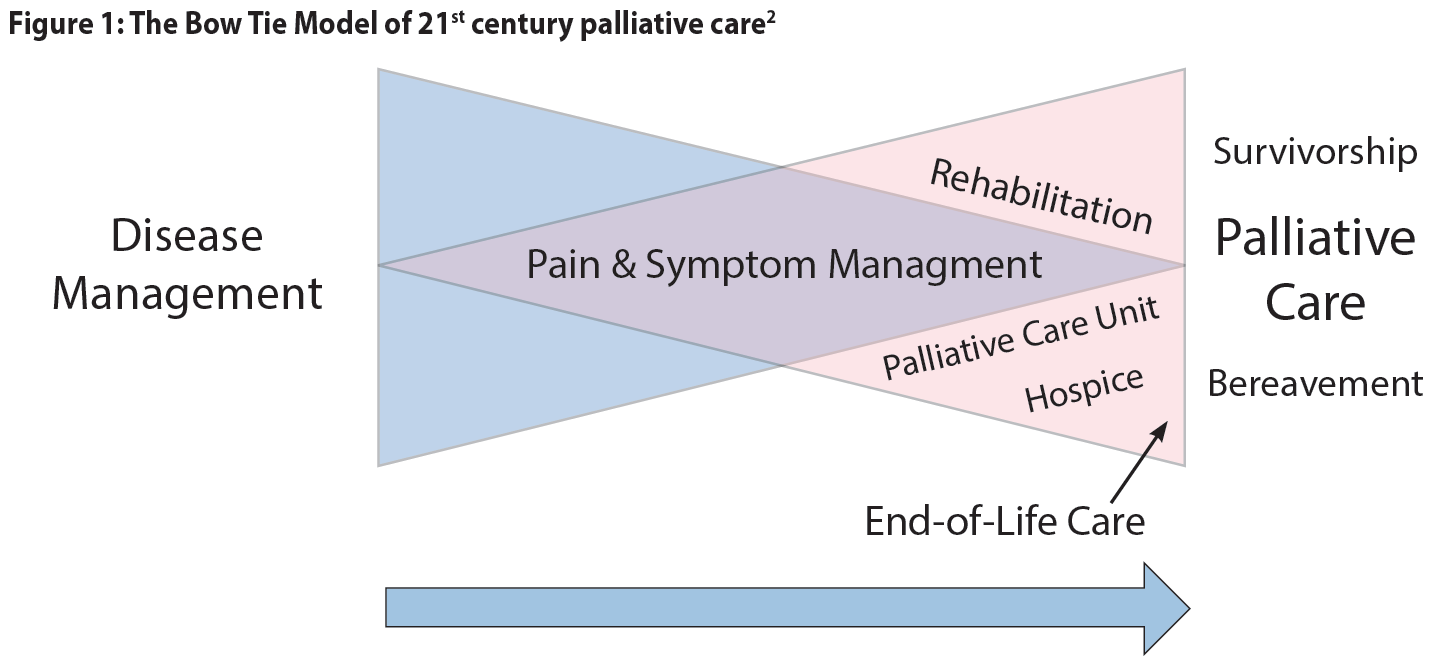

The bow tie model of 21st century palliative care consists of two overlapping triangles resembling a bow tie, with an arrow pointing from left to right.2 The first triangle represents disease management and the second triangle is palliative care. The base of the palliative care triangle (end of the model) includes both death and survival as possible outcomes. The arrow indicates that this is a dynamic process with a gradual switch in focus. The key difference between this and traditional models is that survivorship is included as a possible outcome.

Patients diagnosed with incurable cancer or advanced disease may not identify themselves as requiring palliative care. A palliative approach addresses the need for pain and symptom management, and the psychosocial and spiritual support of patients and their families, even if they choose to undergo life-prolonging treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and/or surgery.

Patients diagnosed with incurable cancer or advanced disease may not identify themselves as requiring palliative care. A palliative approach addresses the need for pain and symptom management, and the psychosocial and spiritual support of patients and their families, even if they choose to undergo life-prolonging treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and/or surgery.

A proactive chronic disease management approach will help prevent care gaps that may occur during transitions in care and/or when the patient is not supported by a cancer agency or community hospice palliative care program.

Assessment

A palliative approach is needed for patients living with active, progressive, life-limiting illnesses who need pain and symptom management and support around practical or psychosocial issues, have care needs that would benefit from a coordinated or collaborative care approach, and/or have frequent emergency room visits. Assess where patients are in their illness trajectory, functional status, and symptom burden. Clarify goals of care in a culturally sensitive manner.

Estimating prognosis allows optimal use of limited time for patients and families. Rapid change in clinical condition is an understandable and helpful sign. Although prognoses can only be estimated, poor prognostic factors include:

- progressive weight loss (especially > 10% over 6 months);

- rapidly declining level on the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) (refer to Appendix A: Palliative Performance Scale);

- dyspnea;

- dysphagia; and

- cognitive impairment.

Investigations (Refer to Appendix B: Possible Investigations and Interventions)

Before ordering investigations, ensure that the results will change management to improve quality of life and/or prognostication, consistent with the patient’s goals of care. Investigations may be indicated to:

- better understand and manage distressing clinical complications;

- assist in determining prognosis;

- clarify appropriate goals of care; and

- determine whether all options have been considered before admission to hospice.

Evaluate performance status and symptom burden in order to accurately assess a patient’s need for added supports and symptom management. Assessment scales are commonly used to facilitate communication and collaboration among providers (e.g. Appendix A: Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), Associated Document: Supportive & Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICTTM), and Appendix C: Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESASr)).

1. Monitor patient’s functional capacity

Use the PPS (refer to Appendix A: Palliative Performance Scale) to base care on a patient’s functional capacity and prognosis. “The single most important predictive factor in cancer is performance status and functional ability – if patients are spending more than 50% of their time in bed/lying down, prognosis is likely to be about three months or less”. 3 The SPICT™ outlines general and disease-specific indicators and is used to assess patients for the BC Palliative Care benefits program (Associated Document: Information about BC Palliative Care Benefits).

2. Coordinate care with allied health care providers

Organize care coordination around key illness transitions.4 To enhance coordination with allied health providers involved in the care of the patient, the following steps are recommended:

Transition 1: Disease advancement (would not be surprised if patient died in the next year)

- Identify and register patient in need of palliative care.

- Initiate advance care planning.

- Identify the patient's values and beliefs.

- Clarify illness trajectory, possible complications, prognosis, and expected outcomes to inform goals of care.

- Consider the need for referral/coordination with Home and Community Care.

- Consider referral to Home Care Nursing when patient’s PPS is transitioning from 70% to 60% or lower.

Transition 2: Decompensation, experiencing life-limiting illness (prognosis approximately six months and PPS 50%)

- Discuss care coordination.

- Consider hospice palliative care referrals.

- Consider an application to BC Palliative Care Drug Plan (Plan P) when patient is in last six months of life and has a PPS of 50% or less (refer to Associated Document: Information about BC Palliative Care Benefits).

Transition 3: Dependency and symptom increase (concern about ability to support client at home given increasing care needs)

- Initiate End-of-Life care planning, including assessment of preferred location for care.

Transition 4: Decline and last days (anticipating death in the next few days or weeks)

- Discuss medications required in home with Home Care Nursing.

- Assess if patient and family are comfortable with their End-of-Life care plan.

- Support required changes to End-of-Life care plan.

Transition 5: Death and bereavement

- Perform follow-up bereavement visit or call.

Refer to Associated Document: Practice Support Program (PSP) End-of-Life Care Algorithm.

3. Evaluate symptom burden

Use a scale like the ESASr (refer to Appendix C: Edmonton Symptom Assessment System) to assess symptom management. Pain and other symptoms are assigned a numerical rating between 0 (none) and 10 (most severe imaginable). Record the level and range of symptom severity, aiming for ≤ 3 and thoroughly assess for values ≥ 4. For ESASr symptom scores, using pain as an example, a useful frame of reference is:5

- 0-1: no pain or minimal pain.

- 3: able to watch TV or read newspaper without paying much attention to pain.

- 5: pain is too distracting to find much pleasure in activities (e.g., TV, reading).

- > 5: on the verge of being or already overwhelmed by pain.

- 10: the worse pain that you could imagine.

4. Establish goals of care with patients and families

As the underlying condition progresses, a patient’s goals of care often become less disease-specific and more palliative.

Discuss a patient’s wishes before clinical deterioration, possibly over several visits. Start by determining how much the patient desires to know about their disease and how much they desire to participate in decision making. When translation is required, a professional interpreter (rather than a family member) is advisable.

- Enquire regarding cultural and individual preferences. Factors such as age, gender, religion, and culture can affect patient and caregiver approach to palliative care and conversations about end of life. The Canadian Virtual Hospice has resources supporting culturally-sensitive palliative care including the online resource livingmyculture.ca.

- Well-established communication strategies such as “The Serious Illness Conversation Guide”6 can be helpful for discussing goals of care. Refer to Associated Document: The Serious Illness Conversation Guide.

- Determine the patient’s understanding of the disease and condition.

- Discuss the anticipated course of the illness, treatment choices, and options in relation to a patient’s preferences, needs, and expectations.

- Document advance care planning discussions and the existence of any Advance Directive/Representation Agreement.

- In the absence of a representation agreement, identify a Temporary Substitute Decision Maker (TSDM) (see page 28 of the My Voice guide, available at: www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/family-social-supports/seniors/health-safety/advance-care-planning).

- Document whether the following forms have been completed (refer to Associated Document: Resource Guide for Patients and Caregivers and Resource Guide for Practitioners):

- No CPR (https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/more/health-features/no-cpr-form),

- Notification of Expected Death in the Home (www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/forms/3987fil.pdf), and

- Medical Orders for Scope of Treatment (MOST) (refer to your health authority for more information).

- Establish plans for key decisions for acute episodes, crisis events, and declining function in relation to life-sustaining therapies and hospitalizations, considering all comorbidities.

- Clarify the patient’s preferred place of care.

- Establish the caregiver’s ability to provide care at home, if that is the patient’s preference.

- Review the goals of care regularly, and when there is a change in clinical status.

5. Management strategies: non-pharmacologic

Lifestyle management

- Exercise: Regular exercise and activity has been proven to improve quality of life and function in cancer survivors.7

- Nutrition: Nutritional needs are different for patients with cancer as their appetite is often reduced and forcing additional food may contribute to nausea or vomiting. When the goal is life prolongation, a consultation with a dietitian may be helpful.

- Rest: Fatigue is a common accompaniment of cancer or its treatment. Adequate rest and pacing of activities is important. Poor sleep will contribute to a lower quality of life for both the patient and caregiver.

Family and caregiver support (refer to Associated Document: Resource Guide for Patients and Caregivers).

- Caregivers who take time off work can apply for the Employment Insurance (EI) Compassionate Care Benefit (refer to Associated Document: Resource Guide for Patients and Caregivers).

- Registration can be made to the Palliative Benefits Program when a patient’s life expectancy is estimated to be six months or less (refer to Associated Documents: Information about BC Palliative Care Benefits).

- Completing the “Notification of Expected Death in the Home” form means families can avoid waiting for a physician or nurse to pronounce death.

Patient self-management (refer to Associated Document: Resource Guide for Patients and Caregivers)

- Encourage patients to have an advance care planning discussion with family and/or caregivers (for an example see the “My Voice” booklet in the Resource Guide).

- Symptom reporting: Suggest that patients record symptoms using a numerical rating scale (0 = none to 10 = extreme) and report symptoms consistently ≥ 4.

- Medications: Suggest that patients keep up-to-date medication profiles to carry with them to appointments and ER visits, including flow sheets to record breakthrough medication. Ensure that treatment of incident pain is understood.

- Bowel protocol: Constipation, an opioid side effect, does not improve over time. Provide written instructions for a bowel protocol that patients may self-administer (refer to BCGuidelines.ca - Palliative Care Part 2: Pain and Symptom Management and Associated Document: BCCA Bowel Protocol).

- Providing help 24/7: Includes contact numbers (and hours, where applicable) for the GP on call, home nursing, and HealthLinkBC (call 811).

6. Management strategies: pharmacotherapy

Refer to BCGuidelines.ca - Palliative Care Guideline Part 2: Pain and Symptom Management.

7. Referral to a specialist

Refer to Appendix D: Indications for Referral to a Specialist

8. Indications for referral to a tertiary palliative care unit

Referral is indicated for control of pain and other symptoms when these cannot be met in the community, and for support for severe psychological, spiritual, or social distress.

9. Ongoing care

Planned visits

- A shared care plan, complete with planned follow-up visits, helps patients and families feel supported.

- Planned visits proactively anticipate care transitions and care crises (refer to PSP End-of-Life Care Algorithm: www.pspexchangebc.ca/pluginfile.php/2416/mod_resource/content/1/00.0_EOL_End_of_Life_Algorithm_v8.5.pdf (login required).

- Recommended visit frequency depends on prognosis. For example, if the illness is stable (PPS ≥70%), quarterly visits are recommended, but if the illness is changing monthly, then visit monthly. More frequent planned visits are warranted in the face of more rapid decline.

Monitoring and documentation (refer to Appendix E: Cancer Management Flow Sheet)

- Prognostic factors: Monitor for impending transition or crisis (e.g., new or accelerated weight loss, dyspnea, cognitive impairment, or change in PPS).

- Signs and symptoms: Each visit, record pain scale for each pain type and location.

- Medications: In addition to slow release opioid, record use of breakthrough medications, antinauseants, and bowel protocol. Also consider adjuvant analgesics (refer to BCguidelines.ca Palliative Care Guideline Part 2: Pain and Symptom Management).

- Care plan: Ensure that supports for patient and family are arranged through Home and Community Care and also document discussions regarding patient goals and advance directives.

Palliative care emergencies

Table 1: Palliative care emergencies: recognize and respond

|

Emergency |

Investigation |

Intervention |

|

Spinal cord compression |

Stat MRI (CT if MRI is not available) |

Dexamethasone, surgical decompression and/or radiotherapy |

|

Superior vena cava compression |

CT chest |

Dexamethasone, SVC stent or radiotherapy |

|

Pathological fracture |

X-ray, CT |

Internal/external fixation, sufficient analgesia |

|

Acute renal failure / obstructive nephropathy |

Ultrasound |

Ureteral stents or nephrostomies |

|

Other: airway obstruction, hemorrhage, seizures |

As required |

Anticipate and provide crisis orders |

Abbreviations: MRI - magnetic resonance imaging; CT - computed tomography; SVC - superior vena cava

10. Allied health care and referral to the local hospice palliative care program

- High quality palliative care is generally provided via a team approach and GPs are important team members as they often have good relationships with patients and families and the knowledge and expertise to coordinate and provide care for the whole patient. Team members may include medical specialists, advanced practice nurses, home care nurses, social workers, case managers, pharmacists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, dietitians, spiritual care workers, hospice volunteers, and home support workers.

- Patients are often best educated by allied health providers when it comes to topics such as myths about opioids, proper use of breakthrough medications, managing side effects, accessing help after hours, how to plan a home death, etc.

- Refer to the local hospice palliative care program early in the illness trajectory so patients and their families can learn what supports are available before they are required.

11. Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD)

It is likely that some conversations about end of life may result in patients or families wanting to discuss Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD). A palliative approach to care is appropriate for all people living with chronic life-threatening illness, whether or not they choose MAiD, and specialist palliative care consultation is encouraged if MAiD is being considered. MAiD is intentionally beyond the scope of this guideline. However, practitioners seeking information about it are directed to the following resources:

- BC Ministry of Health: www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/accessing-health-care/home-community-care/care-options-and-cost/end-of-life-care/medical-assistance-in-dying/information-for-providers

12. Actively dying: the End-of-Life Care check list

There are several points to consider when patients enter the dying phase:

- Review a patient’s goals of care, preferred place of care, and what to do in an emergency.

- Refer the patient to home nursing if not already arranged.

- Consider hospice palliative care referrals.

- Ensure that the required forms are completed (No CPR, MOST DNR M1, Notification of Expected Death in the Home).

- Discontinue non-essential medications.

- Arrange for subcutaneous (SC)/transdermal medication administration or a drug kit to be placed in the home when a patient is no longer able to take medications by mouth (refer to Appendix F: Typical Home Drug Kit and Subcutaneous Medication List).

- Arrange for a hospital bed +/- pressure relief mattress.

- Arrange for a Foley catheter, as needed.

- Leave an order for a SC anti-secretion medication (e.g., atropine, glycopyrrolate).

13. Death and bereavement (Refer to BCGuidelines.ca: Palliative Care Part 3: Grief and Bereavement)

Recognition of and preparation for complex grieving optimally takes place before death occurs (refer to risk factors for prolonged grief disorder (complicated grief) in BCGuidelines.ca Palliative Care Part 3: Grief and Bereavement).

At time of death:

- Personally contact the bereaved caregiver/family.

- Provide information about grief and what to expect and refer to resources.

- Arrange follow-up contact.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. [Cited 2016 Oct] Available from http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- Hawley PH . The bow tie model of 21st century palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014; Jan 47(1):e2-5.

- Royal College of General Practitioners. The gold standards framework. Prognostic indicator guidance. 4th Edition. Oct 2011 [Cited 2016 Oct]. Available from http:// www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/cd-content/uploads/files/General%20Files/Prognostic%20Indicator%20Guidance%20October%202011.pdf

- Practice Support Program. PSP End of Life Care Algorithm. c2016 [Cited 2016 Oct]. Available from http://www.gpscbc.ca/psp-learning/end-of-life/tools-resources

- Lynn J, Schuster J, Wilkinson A, Simon LN. Improving care for the end of life: a sourcebook for health care managers and clinicians. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2008.

- Bernacki RE and Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Dec;174(12):1994-2003.

- Cramp F, Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD006145.

Appendices

- Appendix A: Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) (PDF, 86KB)

- Appendix B: Possible Investigations and Interventions (PDF, 332KB)

- Appendix C: Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESASr) (PDF, 231KB)

- Appendix D: Indications for Referral to a Specialist (PDF, 77KB)

- Appendix E: Cancer Management Flow Sheet (PDF, 82KB)

- Appendix F: Typical Home Drug Kit and Subcutaneous Medication List (PDF, 83KB)

Associated Documents

- BCGuidelines.ca – Palliative Care: Resource Guide for Patients and Caregivers (PDF, 850KB)

- BCGuidelines.ca – Palliative Care: Resource Guide for Practitioners (PDF, 491KB)

- BCGuidelines.ca – Information about BC Palliative Care Benefits (PDF, 174KB)

- Supportive & Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICTTM): www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/forms/349_spict_tool.pdf

- Practice Support Program (PSP) End-of-Life Care Algorithm: https://divisionsbc.ca/sites/default/files/Divisions/Thompson%20Region/Attachment%20Library/End-of-Life-Algorithm-v8.5.pdf

- The Serious Illness Guide, developed by Ariadne Labs6 is also available as a resource on the BC Cancer Agency’s Advance Care Planning website. http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/new-patients-site/Documents/SeriousIllnessConversationGuideCard.pdf

- BC Cancer Agency Bowel Protocol: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/family-oncology-network-site/documents/suggestionsfordealingwithconstipation.pdf

- Notification of Expected Death in the Home: www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/forms/3987fil.pdf

- No Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation – Medical Order: www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/forms/302fil.pdf

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the Effective Date.

This guideline was developed by the Family Practice Oncology Network and the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, approved by the British Columbia Medical Association, and adopted by the Medical Services Commission.

|

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

Contact Information: Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, Email: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca Disclaimer The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the “Guidelines”) have been developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The Guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The Guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional. |