Thyroid Function Testing in the Diagnosis and Monitoring of Thyroid Function Disorder

Effective Date: October 24, 2018

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Indications for Testing

- Tests

- Monitoring of Thyroid Disease

- Subclinical Thyroid Disease

- Sick Euthyroid Syndrome

- Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy

- Controversies in Care

- Resources

Scope

This guideline outlines testing for thyroid dysfunction in patients (pediatric and adult), including pregnant women or women planning pregnancy, and the monitoring of patients treated for primary thyroid function disorders. It does not apply to the BC Newborn Screening Program. This guideline outlines testing for thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine (fT4), free triiodothyronine (fT3) and anti-thyroid peroxidase (TPO).

Information on other tests, including thyroglobulin/antithyroglobulin (Tg/anti Tg) and antibodies to the thyroid stimulating hormone receptor (TRAb), are covered in the associated BC Guideline Hormone Testing – Indications and Appropriate Use.

Key Recommendations

- Routine thyroid function testing is not recommended in asymptomatic patients (outside of the BC Newborn Screening Program). Testing may be indicated when non-specific symptoms or signs are present in patients at risk for thyroid disease

- A TSH value within the laboratory reference interval excludes the majority of cases of primary thyroid dysfunction

- If initial TSH testing is normal, repeat testing is unnecessary unless there is a change in clinical condition

- Measurement of fT3 is rarely indicated in suspected thyroid disease

- Screening for undiagnosed hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism should not be performed in hospitalized patients or during acute illness unless hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism is the suspected cause of the clinical presentation or represents a significant co-morbidity

- If a woman is pregnant or planning pregnancy, TSH testing is indicated if she has specific risk factors (see Table 3)

Indications for Testing

Routine thyroid function testing is not recommended in asymptomatic patients (outside of the BC Newborn Screening Program). Testing may be indicated when non-specific symptoms or signs are present in patients who have specific risk factors for thyroid disease. Testing is indicated for patients with a clinical presentation consistent with thyroid disease as delineated in Table 1: Symptoms and Signs of Thyroid Disease below.

Where thyroid testing in an asymptomatic patient has occurred and the patient has been diagnosed with subclinical thyroid disease, see the Subclinical Thyroid Disease section.

If initial testing is normal, repeat testing is unnecessary unless there is a change in clinical condition.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for thyroid disease include1:

- men: age ≥ 60 years2

- women: age ≥ 50 years2

- personal history or strong family history of thyroid disease

- diagnosis of other autoimmune diseases

- past history of neck irradiation

- previous thyroidectomy or radioactive iodine ablation

- drug therapies such as lithium and amiodarone

- dietary factors (iodine excess and iodine deficiency in patients from developing countries); or

- certain chromosomal or genetic disorders (e.g., Turner syndrome3, Down syndrome4 and mitochondrial disease5)

For risk factors during pregnancy, see Table 3 in the Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy section below.

Signs and Symptoms

Table 1: Symptoms and Signs of Thyroid Disease1, 6, 7

This table reflects common manifestations of thyroid disease in adults. Pediatric-specific manifestations of hypothyroidism (e.g., slow growth and delayed osseous maturation8, delayed puberty or precocious puberty (in severe longstanding hypothyroidism)9) or hyperthyroidism (e.g., difficulty gaining weight, growth acceleration, advanced bone age or delayed puberty9) should also be considered in the pediatric context.

| Hypothyroidism: Symptoms and Signs | Hyperthyroidism: Symptoms and Signs | |

|---|---|---|

| Neuropsychiatric |

|

|

| Neuromuscular |

|

|

| Physical Appearance/Voice |

|

|

| Cardiovascular |

|

|

| Thyroid Gland |

|

|

| Thermoregulation |

|

|

| Ophthalmologic |

|

|

| Gastrointestinal |

|

|

| Pituitary Function |

|

|

A. Hypothyroidism rarely causes weight gain in pediatric populations9.

Tests

Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH)

Measurement of TSH is the principal test for the evaluation of thyroid function in the vast majority of circumstances10 provided there is no clinical or historical evidence to suggest damage or disease of the hypothalamic -pituitary axis. Hypothalamic and pituitary disease can cause central hypothyroidism, which is rare11, 12. Central hypothyroidism can be caused by invasive or compressive lesions, iatrogenic factors, injuries, vascular accidents, autoimmune disease, infiltrative disease, congenital conditions and infections11. If central hypothyroidism is being investigated "suspicion of pituitary insufficiency" should be included as a clinical indication and a request for fT4 (with or without TSH) should be indicated in the space provided on the standard out-patient laboratory requisition (see Appendix 1: BC Laboratory Algorithm for Thyroid Tests).

A TSH value within the laboratory reference interval excludes the majority of cases of primary thyroid dysfunction6. The TSH reference interval will vary depending on the testing laboratory. Laboratories in BC retain specimens for 2 to 7 days in case add-on testing is required (see Appendix 1: BC Laboratory Algorithm for Thyroid Tests).

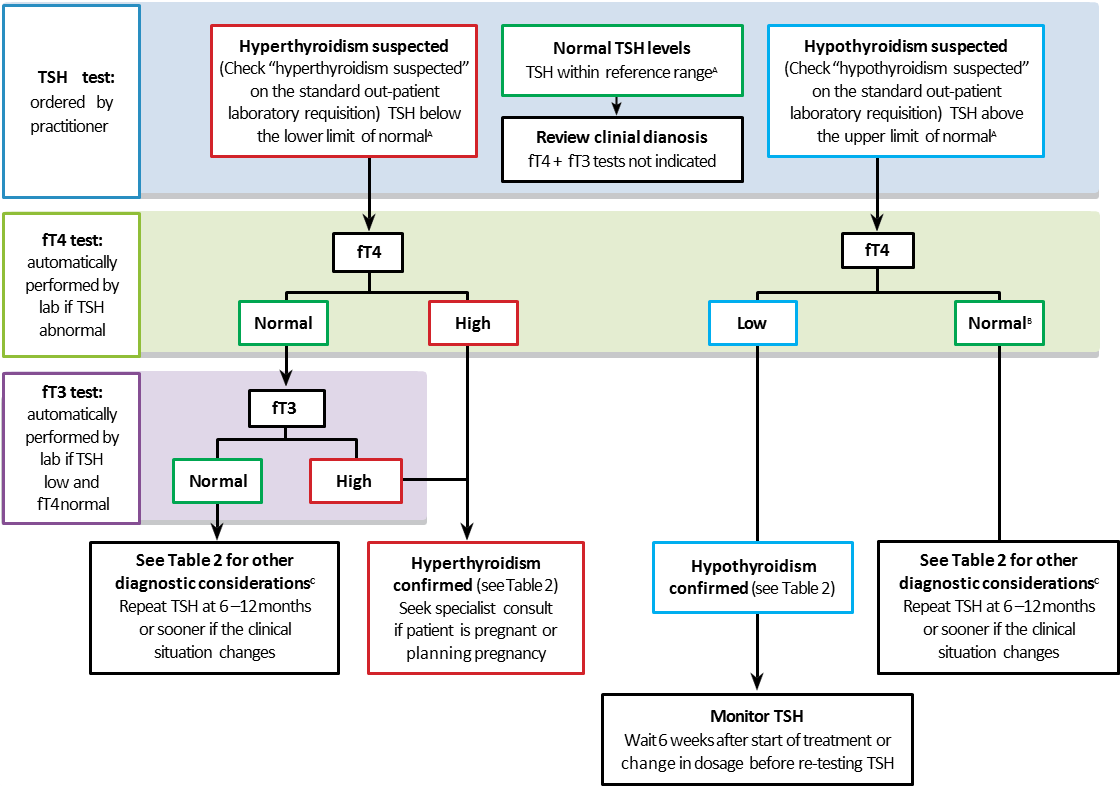

- If "suspected hyperthyroidism" is chosen on the standard out-patient laboratory requisition, the laboratory will perform the TSH test first and then automatically perform the fT4 and fT3 if required

- If "suspected hypothyroidism" is chosen on the standard out-patient laboratory requisition, the laboratory will perform the TSH test first and then automatically perform the fT4 if required

- If free thyroid hormones are ordered without TSH, a clinical indication is required

See Figure 1 for a Clinical Algorithm of Thyroid Function Tests for Diagnosis and Monitoring in Symptomatic Non-Pregnant Patients and Table 2 for Potential Causes of Abnormal Hormone Levels.

Free Thyroxine (fT4) and Free Triiodothyronine (fT3)

Measurements of fT4 and fT3 have replaced those of total T4 and total T3 levels. Laboratories are permitted to substitute free hormone assays when total T3 or T4 have been ordered.

Measurement of fT3 is rarely indicated in suspected thyroid disease6, 13. This is reserved for situations where thyroid disease is suspected clinically and TSH is abnormal, but fT4 is inappropriately normal.

Anti-Thyroid Peroxidase (TPO)

Anti-TPO measurement is not routinely indicated in patients with hypothyroidism as it does not generally change clinical management. In specific circumstances it may be helpful in further clinical decision making. In patients with a goitre or mildly elevated TSH, anti-TPO measurement is used to evaluate whether the cause is autoimmune thyroiditis13. TPO antibody positivity increases the risk of developing hypothyroidism in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism, autoimmune diseases (e.g., type 1 diabetes), chromosomal disorders (e.g., Turner syndrome and Down syndrome) or patients who are on certain drug therapies (e.g., lithium, amiodarone) or are pregnant or postpartum (see Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy section below)13, 14. Once a patient is known to be TPO antibody positive, repeat analysis is not indicated.

There are other thyroid antibody tests with specific indications which are not covered in this guideline and are discussed in the associated BC Guideline Hormone Testing – Indications and Appropriate Use.

Follow-Up Testing

In most cases, ordering a different test is more useful than repeating the same test (e.g., if a patient has specific clinical findings and a TSH result does not appear to correlate with the patient’s clinical status, it may be more appropriate to follow with an fT4 measurement). If fT4 is being ordered to investigate or follow central hypothyroidism, “suspicion of pituitary insufficiency” should be included as a clinical indication and a request for fT4 (with or without TSH) should be written in the space provided on the standard out-patient laboratory requisition.

Consultation with a lab physician or an endocrinologist is recommended when the test result is in conflict with the clinical presentation so that investigation for analytical interferences or rare conditions can be undertaken.

Note that thyroid ultrasound scan is not routinely recommended in patients with abnormal thyroid function tests, unless there is a palpable abnormality of the thyroid gland (Choosing Wisely Endocrinology and Metabolism Recommendation). See the associated BC Guideline Ultrasound Prioritization.

Figure 1: Clinical Algorithm for Thyroid Function Tests for Diagnosis and Monitoring in Symptomatic Non-Pregnant Patients.

This algorithm only applies to patients with an intact hypothalamic-pituitary axis and does not apply to hospitalized patients (Sick Euthyroid Syndrome). For information during pregnancy, see the Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy section. For laboratory testing procedures, see Appendix 1: BC Laboratory Algorithm for Thyroid Tests.

Notes:

- TSH reference intervals may vary depending on the testing lab.

- Overt primary hypothyroidism is diagnosed when the TSH is elevated and the fT4 is low. A decision to treat is often made if the TSH is >10 mU/L even if the fT4 is within the reference range.

- An abnormal TSH level, associated with a normal fT4 and fT3 level is most often due to subclinical thyroid dysfunction. Rarely, it may be related to a lab artefact such as antibody interference.

Table 2. Potential Causes of Abnormal Hormone Levels (TSH, fT4 and fT3)

| Causes of High TSH15–17 | Laboratory Result | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|

|

Hypothyroidism

|

TSH high, fT4 low6 |

See Monitoring: Hypothyroidism or Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy |

|

Subclinical hypothyroidism

|

TSH high (usually less than 10 mU/L)A, |

See Subclinical Hypothyroidism or Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy |

|

Recovery from non-thyroidal illness

|

Testing not usually indicated |

See Sick Euthyroid Syndrome |

|

Very rare causes

|

TSH high (or normal), fT4 high15, 16 |

| Causes of Low TSH15–17 | Laboratory Result | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|

|

Hyperthyroidism or other causes of thyrotoxicosis

|

TSH low, fT4 high6 |

See Monitoring: Hyperthyroidism |

|

Hyperthyroidism or other causes of thyrotoxicosis

|

TSH low, fT4 normal/low, fT3 high6 |

See Monitoring: Hyperthyroidism |

|

Subclinical hyperthyroidism |

TSH lowA, fT4 normal, fT3 normal21 |

See Subclinical Hyperthyroidism |

|

Sick Euthyroid Syndrome

|

Testing not usually indicated |

See Sick Euthyroid Syndrome |

|

Very rare causes

|

TSH normal (or low), fT4 low6 |

- Treatment is considered when TSH is above 10 mU/L18 for subclinical hypothyroidism or below 0.1 mU/L21 for subclinical hyperthyroidism.

- Assay artefact may cause abnormal laboratory results. Immunoassays for thyroid function tests are subject to analytical interference due to heterophile antibodies22, variant TSH isoforms by glycosylation22, macro TSH (TSH in combination with IgG antibody)22, or high dose biotin administration23. If an assay artefact is suspected, consult with a lab physician.

Monitoring of Thyroid Disease

Hypothyroidism

Since TSH values change slowly24, frequent repeat testing is not indicated. TSH may be repeated after at least 6 weeks following a change in thyroid hormone replacement dose or in a patient’s clinical status13. Care should be taken not to overtreat with levothyroxine, as it can result in atrial fibrillation (more commonly in the elderly) and bone loss in postmenopausal women13.

Once TSH has normalized with treatment, it should be checked annually unless a new indication arises. This confirms adequacy of treatment dose and compliance with therapy.

Note that even within the reference interval, TSH levels in the same individual can vary by 50% when measured at different times of day, with lowest values in the late afternoon and highest values at midnight25. In individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism, TSH values can vary by up to 40% even when measured at the same time on different days without indicating a change in thyroid function26. As long as TSH remains within the reference interval, changes over time are not important.

Patients taking lithium and amiodarone are at increased risk for hypothyroidism13 and monitoring of TSH is recommended every 6 months. Amiodarone treatment may also lead to amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis and monitoring is recommended every 3-6 months21.

Hyperthyroidism

To monitor patients on treatment for Graves’ disease or other causes of hyperthyroidism, allow at least one month or longer before repeating fT4 and TSH levels since pituitary secretion of TSH may be suppressed for protracted periods following hyperthyroidism21. Until TSH suppression resolves, initial treatment and dosing decisions should be based on fT4, or in the case of T3 thyrotoxicosis, on fT321.

Patients taking amiodarone are at increased risk of amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis and monitoring is recommended every 3–6 months21.

Hypothalamic or Pituitary Disease

TSH is only useful as a measure of thyroid disease if the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis is intact. When pituitary or hypothalamic disease is suspected, fT4 measurement is required to make the diagnosis or assess adequacy of thyroid replacement therapy11, 12.

Subclinical Thyroid Disease

Subclinical thyroid disease is a biochemical diagnosis and typically has either no symptoms or non-specific symptoms, is more common in women, and prevalence increases with advanced age18, 21.

Subclinical Hypothyroidism

In subclinical hypothyroidism, TSH is elevated in the presence of normal levels of fT4 (see Table 2)13, 18.

Treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism is recommended when TSH rises above 10 mU/L18. Treatment can be considered when TSH is between the upper limit of the reference interval but ≤10 mU/L and any of the following are present13:

- symptoms suggestive of hypothyroidism

- elevated TPO antibodies

- evidence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, or associated risk factors for these diseases; or

- pregnancy (see Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy section below)

The prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism in the general population is between 4.3–8.5%13. Every year, 2.6% of subclinical hypothyroidism patients without elevated TPO antibodies and 4.3% of subclinical hypothyroidism patients with elevated TPO antibodies progress to overt hypothyroidism13.

Monitoring of TSH in untreated patients with subclinical hypothyroidism is indicated at 6–12 month intervals, or sooner if the clinical situation changes27.

Subclinical Hyperthyroidism

In subclinical hyperthyroidism, the TSH is suppressed in the presence of normal levels of fT4 (see Table 2)21. Subclinical hyperthyroidism is less common, with a prevalence of 0.7%21.

Patients with atrial fibrillation or osteoporosis should be screened for hyperthyroidism. In patients over age 60 with TSH 0.1 mU/L but with a normal fT4, the relative risk for atrial fibrillation increases threefold28. Post-menopausal women with subclinical hyperthyroidism may have an increased rate of bone loss29. In the elderly, there is a higher cardiovascular risk and an increased risk of fracture. Treatment of subclinical hyperthyroidism should be considered in the elderly21, 30. Patients with subclinical hyperthyroidism due to multi-nodular goitre or toxic adenoma are unlikely to normalize and are therefore more likely to benefit from treatment.

Sick Euthyroid Syndrome

In Sick Euthyroid Syndrome (Non-Thyroidal Illness Syndrome), the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis is affected by a non-thyroid illness. It occurs in patients without a previously diagnosed thyroid disease31.

Almost any condition that can make a person ill can cause Sick Euthyroid Syndrome and the elderly are more susceptible because of multiple co-morbid conditions15. The syndrome is acute and spontaneously reverses and occurs commonly after surgery, during fasting, during many acute febrile illnesses, and after acute myocardial infarction. Malnutrition, renal and cardiac failure, hepatic diseases, uncontrolled diabetes, cerebrovascular diseases, and malignancy can also produce abnormalities in thyroid function tests15.

Testing

Ideally, thyroid function tests should not be performed in hospitalized patients unless hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism is the suspected cause of the clinical presentation or represents a significant co-morbidity. However, where thyroid testing has occurred, any abnormal results should be interpreted with caution and with a realization that Sick Euthyroid Syndrome is the most likely explanation for the finding if performed in hospitalized patients rather than true thyroid disease.

Multiple patterns of hormone levels are possible (see Table 2); abnormalities fluctuate during the course of illness and recovery. However, usually fT3 is low, fT4 is low in some sicker patients, and TSH is low or normal12,16. As patients recover from their illness, TSH may normalize or become elevated19.

TSH levels must be interpreted with caution in hospitalized individuals. However, values below < 0.1 mU/L or > 20 mU/L merit a consultation with endocrinology or internal medicine10. Levothyroxine replacement has not been shown to be beneficial and should not be used in patients with Sick Euthyroid Syndrome12.

Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy

Currently, there is insufficient evidence to advocate for universal screening (see Universal Screening During Pregnancy in the Controversies in Care Section below). Based on the 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Disease During Pregnancy and the Postpartum, if a woman is pregnant or planning pregnancy, TSH testing is indicated if she has any of the risk factors listed in Table 314. Pregnant women often experience symptoms that can be non-specific or vague and as such, it may be difficult to distinguish between symptoms of thyroid dysfunction and normal changes of pregnancy. Clinicians should have a low threshold for TSH testing in pregnancy.

Table 3. Risk Factors for Thyroid Disease in Women who are Pregnant or Anticipating Becoming Pregnant14

|

Hypothyroidism in Pregnancy and Postpartum

Research data support a possible connection between untreated overt maternal hypothyroidism and neuropsychological impairment in the offspring34, 35. If hypothyroidism has been diagnosed before or during pregnancy, treatment should be adjusted to achieve a TSH level within the normal trimester specific reference interval.

First trimester reference intervals, in particular, are less than the normal population reference interval. Laboratories in BC should report trimester specific reference intervals as an appended comment on all women of child bearing age. Treatment should be initiated for women whose TSH is above the trimester specific upper limit of normal as reported by the laboratory (see Treatment of Women with Subclinical Hypothyroidism in the Controversies in Care Section below).

A preconception TSH between the lower reference limit and 2.5 mU/L is recommended in women being actively treated for hypothyroidism14.

In women with overt and subclinical hypothyroidism (treated or untreated) and women at risk for hypothyroidism (euthyroid patients who are TPO antibody positive, post-hemithyroidectomy or treated with radioactive iodine), TSH should be measured every 4–6 weeks until midgestation and at least once near 30 weeks gestation14.

In women being treated for hypothyroidism, levothyroxine replacement dosage may need to increase by 25–50% during pregnancy, particularly in the first trimester20, 33. After starting thyroid hormone replacement or a dose change during pregnancy, TSH should be remeasured every 4–6 weeks20, 33.

Postpartum

After delivery, most women treated for hypothyroidism will need a decrease in the levothyroxine dose that they received during pregnancy. TSH should be evaluated 6 weeks after the dose change14.

Hyperthyroidism in Pregnancy and Postpartum

Hyperthyroid patients should have appropriate specialist consultation (endocrinologist or maternal-fetal medicine (e.g., obstetric internal medicine)) when contemplating pregnancy or during pregnancy.

In the course of a normal pregnancy, TSH may be low in the first trimester, when human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) peaks. Pathological causes of low TSH in pregnancy may include multiple gestation, hyperemesis gravidarum and molar pregnancy14. In this context, a normal fT4 generally excludes hyperthyroidism14, 20. After hCG mediated hyperthyroidism, the most common pathological cause of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy is autoimmune Grave’s disease. Toxic multinodular goitre and toxic adenoma are less common than autoimmune causes14.

During pregnancy, if TSH is low, repeat the TSH along with fT414 (using laboratory reported pregnancy specific reference intervals). If TSH is still low and fT4 is high, refer to a specialist in endocrinology or maternal-fetal medicine (e.g., obstetric internal medicine). If TSH is still low but fT4 is normal, repeat testing in 4 weeks is suggested. If TSH is still low referral to a specialist is recommended.

Postpartum

Because of changes in the modulation of the immune system, there is an increased risk of thyroiditis and new presentation or relapse of Graves’ disease in the postpartum period14. One study found that hyperthyroidism diagnosed within 3 months of delivery was most often caused by postpartum thyroiditis while hyperthyroidism diagnosed after 6.5 months was caused by Graves’ disease36.

If a patient is persistently hyperthyroid postpartum, referral to an appropriate specialist in endocrinology or maternal-fetal medicine (e.g., obstetric internal medicine) is recommended.

Postpartum Thyroiditis

Postpartum thyroiditis is an autoimmune disorder and the presence of anti-TPO antibodies increases the risk of disease37. This condition occurs in approximately 5% of women in the first year postpartum37.

Postpartum thyroiditis is often mild and transient. There is insufficient evidence to recommend screening all women for postpartum thyroiditis. Women previously known to be TPO antibody positive should have a TSH performed at 3 and 6 months postpartum or as clinically indicated33. The disorder may present as hyperthyroidism followed by hypothyroidism and subsequent recovery of normal thyroid function. Some women may present with hypothyroidism without a hyperthyroid interval and may remain hypothyroid14. Up to 10–50% of the women who have had postpartum thyroiditis will go on to develop permanent primary hypothyroidism after a postpartum thyroiditis episode14.

An annual TSH is recommended in patients with a history of postpartum thyroiditis14. There is a significant risk for recurrent postpartum thyroiditis in subsequent pregnancies14.

Controversies in Care

Controversies in Care: Universal Screening During Pregnancy

There is clear evidence that treating a pregnant woman known to be hypothyroid has important benefits14. Treatment reduces adverse pregnancy outcomes including preterm delivery or miscarriage38 and neuropsychological impairment of the offspring is associated with hypothyroidism34. At one time, studies suggested that failure to detect even subclinical hypothyroidism might have similar consequences34, 39. This led some groups to recommend that every woman be screened40. Subsequent better designed studies have not confirmed these concerns41. In fact, harm could occur when pregnant women are overtreated42. If a woman has risk factors, TSH testing is specifically recommended in early pregnancy (see the section on Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy).14 In a woman without symptoms and without risk factors, testing is discretionary.

Controversies in Care: Treatment of Pregnant Women with Subclinical Hypothyroidism

Although there is no strong evidence to support routinely measuring TPO antibodies in pregnant women, the American Thyroid Association recommends that treatment may be initiated at lower TSH levels in women known to be TPO antibody positive14. If the TSH value is above 2.5 mU/L but within the reference interval, some practitioners would consider treating if the TPO antibody is positive.

Resources

Practitioner Resources

- RACE: Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise Program – www.raceconnect.ca

A telephone consultation line for select specialty services for physicians, nurse practitioners and medical residents. If the relevant specialty area is available through your local RACE line, please contact them first. Contact your local RACE line for the list of available specialty areas. If your local RACE line does not cover the relevant specialty service or there is no local RACE line in your area, or to access Provincial Services, please contact the Vancouver Coastal Health Region/Providence Health Care RACE line.- Vancouver Coastal Health Region/Providence Health Care: www.raceconnect.ca

Available Monday to Friday, 8 am to 5 pm at 604-696-2131 (Vancouver area) or 1-877-696-2131 (toll free) - Northern RACE: 1-877-605-7223 (toll free)

- Kootenay Boundary RACE: www.divisionsbc.ca/kootenay-boundary/our-impact/team-based-care/race-line 1-844-365-7223 (toll free)

- Fraser Valley RACE: www.raceapp.ca (download at Apple and Android stores)

- South Island RACE: www.raceapp.ca/ (download at Apple and Android stores) or see www.divisionsbc.ca/south-island/race

- Note that endocrinology on Vancouver Island is available through the Royal Jubilee Hospital/Victoria General Hospital on call endocrinologist. The on call endocrinologist can be reached through intranet.viha.ca or the Royal Jubilee Hospital switchboard.

- Vancouver Coastal Health Region/Providence Health Care: www.raceconnect.ca

- Pathways – PathwaysBC.ca

An online resource that allows GPs and nurse practitioners and their office staff to quickly access current and accurate referral information, including wait times and areas of expertise, for specialists and specialty clinics. In addition, Pathways makes available hundreds of patient and physician resources that are categorized and searchable.

References

- Rugge JB, Bougatsos C, Chou R. Screening for and Treatment of Thyroid Dysfunction: An Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 118. AHRQ Publication No. 15-05217-EF-1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2014. (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews).

- Hennessey JV, Klein I, Woeber KA, Cobin R, Garber JR. Aggressive case finding: a clinical strategy for the documentation of thyroid dysfunction. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Aug 18;163(4):311–2.

- Radetti G, Mazzanti L, Paganini C, Bernasconi S, Russo G, Rigon F, et al. Frequency, clinical and laboratory features of thyroiditis in girls with Turner’s syndrome. The Italian Study Group for Turner’s Syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 1995 Aug;84(8):909–12.

- Korsager S, Chatham EM, Ostergaard Kristensen HP. Thyroid function tests in adults with Down’s syndrome. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1978 May;88(1):48–54.

- Chow J, Rahman J, Achermann JC, Dattani MT, Rahman S. Mitochondrial disease and endocrine dysfunction. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017 Feb;13(2):92–104.

- J. Larry Jameson, Anthony P. Weetman. Disorders of the Thyroid Gland. In: Anthony Fauci, Eugene Braunwald, Dennis Kasper, Stephen Hauser, Dan Longo, J. Jameson, et al., editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. p. 2224–47.

- Marie-Dominique Beaulieu. Screening for Thyroid Disorders and Thyroid Cancer in Asymptomatic Adults. In: Richard B. Goldbloom, editor. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care | The Red Brick: The Canadian Guide to Clinical Preventive Health Care (1994). p. 612–8.

- Rivkees SA, Bode HH, Crawford JD. Long-term growth in juvenile acquired hypothyroidism: the failure to achieve normal adult stature. N Engl J Med. 1988 Mar 10;318(10):599–602.

- Hanley P, Lord K, Bauer AJ. Thyroid Disorders in Children and Adolescents: A Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Oct 1;170(10):1008–19.

- Dufour DR. Laboratory Tests of Thyroid Function: Uses and Limitations. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007 Sep 1;36(3):579–94.

- Persani L. Central Hypothyroidism: Pathogenic, Diagnostic, and Therapeutic Challenges. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Sep 1;97(9):3068–78.

- Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, Burman KD, Cappola AR, Celi FS, et al. Guidelines for the Treatment of Hypothyroidism: Prepared by the American Thyroid Association Task Force on Thyroid Hormone Replacement. Thyroid. 2014 Sep 29;24(12):1670–751.

- Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, Hennessey JV, Klein I, Mechanick JI, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Endocr Pract Off J Am Coll Endocrinol Am Assoc Clin Endocrinol. 2012 Dec;18(6):988–1028.

- Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, Brown RS, Chen H, Dosiou C, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Disease During Pregnancy and the Postpartum. Thyroid Off J Am Thyroid Assoc. 2017 Mar;27(3):315–89.

- Rehman SU, Cope DW, Senseney AD, Brzezinski W. Thyroid disorders in elderly patients. South Med J. 2005 May;98(5):543–9.

- Koulouri O, Moran C, Halsall D, Chatterjee K, Gurnell M. Pitfalls in the measurement and interpretation of thyroid function tests. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013 Dec;27(6):745–62.

- Toolkit: Less is More with T3 & T4 [Internet]. Choosing Wisely Canada. [cited 2017 Oct 6]. Available from: https://choosingwiselycanada.org/perspective/toolkit-t4-t3/

- Pearce SHS, Brabant G, Duntas LH, Monzani F, Peeters RP, Razvi S, et al. 2013 ETA Guideline: Management of Subclinical Hypothyroidism. Eur Thyroid J. 2013 Dec;2(4):215–28.

- Warner MH, Beckett GJ. Mechanisms behind the non-thyroidal illness syndrome: an update. J Endocrinol. 2010 Apr 1;205(1):1–13.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 148: Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Apr;125(4):996–1005.

- Ross DS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, Greenlee MC, Laurberg P, Maia AL, et al. 2016 American Thyroid Association Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Hyperthyroidism and Other Causes of Thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid Off J Am Thyroid Assoc. 2016 Oct;26(10):1343–421.

- Estrada JM, Soldin D, Buckey TM, Burman KD, Soldin OP. Thyrotropin isoforms: implications for thyrotropin analysis and clinical practice. Thyroid Off J Am Thyroid Assoc. 2014 Mar;24(3):411–23.

- Li D, Radulescu A, Shrestha RT, Root M, Karger AB, Killeen AA, et al. Association of Biotin Ingestion With Performance of Hormone and Nonhormone Assays in Healthy Adults. JAMA. 2017 Sep 26;318(12):1150–60.

- Kaplan MM. Clinical Perspectives in the Diagnosis of Thyroid Disease. Clin Chem. 1999 Aug 1;45(8):1377–83.

- Caron PJ, Nieman LK, Rose SR, Nisula BC. Deficient nocturnal surge of thyrotropin in central hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986 May;62(5):960–4.

- Karmisholt J, Andersen S, Laurberg P. Variation in thyroid function tests in patients with stable untreated subclinical hypothyroidism. Thyroid Off J Am Thyroid Assoc. 2008 Mar;18(3):303–8.

- Hennessey JV, Espaillat R. Diagnosis and Management of Subclinical Hypothyroidism in Elderly Adults: A Review of the Literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 Aug 1;63(8):1663–73.

- Sawin CT, Geller A, Wolf PA, Belanger AJ, Baker E, Bacharach P, et al. Low serum thyrotropin concentrations as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in older persons. N Engl J Med. 1994 Nov 10;331(19):1249–52.

- Faber J, Jensen IW, Petersen L, Nygaard B, Hegedüs L, Siersbaek-Nielsen K. Normalization of serum thyrotrophin by means of radioiodine treatment in subclinical hyperthyroidism: effect on bone loss in postmenopausal women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1998 Mar;48(3):285–90.

- Toft AD. Clinical practice. Subclinical hyperthyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2001 Aug 16;345(7):512–6.

- Farwell A. Thyroid Hormone Therapy is not Indicated in the Majority of Patients with the Sick Euthyroid Syndrome. Endocr Pract. 2008 Dec 1;14(9):1180–7.

- Lothian Guidance for Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Dysfunction in Pregnancy. [Internet]. [cited 2017 Dec 29]. Available from: http://www.nhslothian.scot.nhs. uk/Services/A-Z/DiabetesService/InformationHealthProfessionals/MUHEndocrineManagementProtocols/007b_Thyroid Function Testing in Primary Care Pregnancy Guidance 17.10.08.pdf

- De Groot L, Abalovich M, Alexander EK, Amino N, Barbour L, Cobin RH, et al. Management of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy and postpartum: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Aug;97(8):2543–65.

- Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Allan WC, Williams JR, Knight GJ, Gagnon J, et al. Maternal thyroid deficiency during pregnancy and subsequent neuropsychological development of the child. N Engl J Med. 1999 Aug 19;341(8):549–55.

- Pop VJ, Kuijpens JL, van Baar AL, Verkerk G, van Son MM, de Vijlder JJ, et al. Low maternal free thyroxine concentrations during early pregnancy are associated with impaired psychomotor development in infancy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999 Feb;50(2):149–55.

- Ide A, Amino N, Kang S, Yoshioka W, Kudo T, Nishihara E, et al. Differentiation of postpartum Graves’ thyrotoxicosis from postpartum destructive thyrotoxicosis using antithyrotropin receptor antibodies and thyroid blood flow. Thyroid Off J Am Thyroid Assoc. 2014 Jun;24(6):1027–31.

- Stagnaro-Green A. Approach to the Patient with Postpartum Thyroiditis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Feb 1;97(2):334–42.

- Vissenberg R, van den Boogaard E, van Wely M, van der Post JA, Fliers E, Bisschop PH, et al. Treatment of thyroid disorders before conception and in early pregnancy: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2012 Jul;18(4):360–73.

- Allan WC, Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Williams JR, Mitchell ML, Hermos RJ, et al. Maternal thyroid deficiency and pregnancy complications: implications for population screening. J Med Screen. 2000;7(3):127–30.

- Gharib H, Tuttle RM, Baskin HJ, Fish LH, Singer PA, McDermott MT. Subclinical Thyroid Dysfunction: A Joint Statement on Management from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the American Thyroid Association, and The Endocrine Society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Jan 1;90(1):581–5.

- Casey BM, Thom EA, Peaceman AM, Varner MW, Sorokin Y, Hirtz DG, et al. Treatment of Subclinical Hypothyroidism or Hypothyroxinemia in Pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2017 02;376(9):815–25.

- Korevaar TIM, Muetzel R, Medici M, Chaker L, Jaddoe VWV, Rijke YB de, et al. Association of maternal thyroid function during early pregnancy with offspring IQ and brain morphology in childhood: a population-based prospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016 Jan 1;4(1):35–43.

Abbreviations

fT4 - Free thyroxine

fT3 - Free triiodothyronine

hCG - human chorionic gonadotropin

TPO - Thyroid peroxidase

TSH - Thyroid stimulating hormone

Diagnostic Codes

244 (Hypothyroidism), 242 (Hyperthyroidism)

Appendices

Contributors to guideline

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the Effective Date.

The guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee in collaboration with BC’s Agency for Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and adopted by the Medical Services Commission.

The Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

- encourage appropriate responses to common medical situations

- recommend actions that are sufficient and efficient, neither excessive nor deficient

- permit exceptions when justified by clinical circumstances

Contact Information:

Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee

PO Box 9642 STN PROV GOVT

Victoria BC V8W 9P1

Email: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca

Website: www.BCGuidelines.ca

Disclaimer

The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the “Guidelines”) have been developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The Guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The Guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional.