Urinary Tract Infections in the Primary Care Setting – Investigation

Effective Date: July 29, 2020

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Rationale

- Urine Collection and Storage

- Tests for UTI

- UTI Classification

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Methodology

- Resources

- Appendix 1 – Point of care urine collection prior to urine culture

- Appendix 2 - Interpretation of urine testing results reported by laboratories in BC

Scope

This protocol provides guidance on appropriate testing for suspected urinary tract infection (UTI) in adults ≥ 16 years. It also includes guidance in certain populations with potential asymptomatic bacteriuria, such as the elderly, pregnant women and those who will undergo urological procedures.

Individual antibiotic recommendations and testing for sexually transmitted infections are out of scope. A link to resources for antibiotic management is provided. Please see the BC Centre for Disease Control website for information on testing for sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Key Recommendations

- UTI is a clinical diagnosis.

- Urine microscopy is NOT recommended for investigating UTI.1,2

-

Urine dipstick is more helpful in some scenarios than others:

In women with a clear presentation of acute cystitis (high pre-test probability), the dipstick is not required as the result will not change management. A negative dipstick is not sensitive enough to rule out infection in this scenario.3

However, in women with atypical or unclear symptoms (low pre-test probability), a positive urine dipstick can support the diagnosis, while a negative urine dipstick can rule out UTI.4

Male UTIs are atypical and dipstick testing is warranted for suspected UTI.5

-

Urine culture is not required in most cases of cystitis. It should be requested only when there is a higher risk of resistant uropathogen, or in specific circumstances to confirm the diagnosis (see Table 2).

-

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is common and does NOT require treatment in most patients (see Table 3).

Two exceptions where screening for and antibiotic treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria are warranted are: a) in pregnant women; and b) in those who will undergo urological procedures with mucosal trauma.6

New onset confusion and delirium alone are NOT considered symptoms of UTI. In elderly or debilitated patients with new cognitive or functional changes and no symptoms of UTI, testing for, and treatment of, UTI is not warranted.6,7

-

If indicated, the sample for urine culture should ideally be collected at the laboratory to prevent organism overgrowth. However, if collected at the point of care, the urine should be stored in the fridge for no more than 24 hours prior to submission to the laboratory under refrigerated conditions.

-

Empiric fluoroquinolone therapy should be avoided in the treatment of UTIs due to moderate resistance rates and increased risk of adverse events8–10 (hypoglycemia11, tendonitis12, CNS toxicity12, aortic dissection13 and C. difficile infection14).

Prescribe fluoroquinolone therapy only if the likelihood of resistance is low and the patient has contraindications and/or allergies to other antibiotics.

- Gross hematuria in the absence of other symptoms requires referral to urology. In the case of isolated microscopic hematuria, refer to BCGuidelines.ca: Microscopic Hematuria.

Rationale

- Suspected UTI is one of the most common presentations in the primary care setting.

- Urine dipstick, urine microscopy and urine cultures are some of the most commonly utilized tests.

- UTI can be misdiagnosed, resulting in inappropriate test utilization and/or unnecessary antibiotics.

- Normal bladders are not necessarily sterile. Bacteria in the urine may be normal for an individual and does not need treatment unless/until it causes urinary symptoms or fever, or if they are pregnant or about to have urological procedure with mucosal trauma.

- Asymptomatic bacteriuria is common:6,15

- Premenopausal women – up to 5%

- Postmenopausal women – up to 10%

- Elderly (> 70 years) in the community – up to 16% in women, and up to 7% in men

- Elderly in long-term care (LTC) facilities – up to 50% in women and up to 40% in men

- Indwelling catheter – 100% after 1 month from insertion16

- To promote laboratory and antimicrobial stewardship, this protocol provides the following:

- information on collection and interpretation of urine dipstick, urine microscopy and urine cultures;

- approach to diagnosing and classifying UTI; and

- indications for appropriate testing in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

Urine Collection and Storage

- Prolonged and/or improper storage of urine can negatively impact the analysis.17

- Urine dipstick: may cause false positive nitrites.

- Urine microscopy: cells (i.e. red blood cells and white blood cells) may degrade (at room temperature for > 1 hour; in the fridge > 4 hours)18, resulting in lower counts than actual.

- Urine culture: improper storage conditions (i.e. at room temperature for > 30 minutes) can promote growth of bacteria and result in higher organism counts which can falsely be interpreted as positive.

- The preferred location for urine dipstick is at the point of care (i.e. in the clinic). However, the preferred location for urine microscopy and culture specimen collection is in a laboratory (e.g. patient service centres and hospitals) as this minimizes degradation and/or organism overgrowth from prolonged storage and transportation.

- For urine cultures, in circumstances where either the patient is unable to go to the laboratory, or where the patient will start an antibiotic imminently (and hence suppress organism growth), the patient may have their urine collected at the point of care and transported to the laboratory.

- Avoid collecting urine from old urinary catheters, catheter bags and diapers due to contamination.16,17

- The optimal volume of collected urine is 10-12 cc.

- The urine should be stored in the fridge (2-8°C) for no more than 24 hours prior to submission under refrigerated conditions.

- See Appendix 1 for instructions on point of care urine collection prior to urine culture.

Tests for UTI

Urine dipstick (also known as macroscopic urinalysis, routine urinalysis, chemical reagent strip)

- The test used in the laboratory is the same as the one used in the clinic at the point of care.

- The relevant reagents to diagnose UTI/bacteriuria are (see Appendix 2):19

- Leukocyte esterase (LE) – detects pyuria (white blood cells). Pyuria is not specific for UTI and may occur with other inflammatory disorders (e.g. vaginitis).

- Nitrite – detects presence of certain bacteria, such as E. coli.

- Blood – detects hematuria. For assessing UTI, it should be used in conjunction with LE or nitrite.

- In the case of isolated microscopic hematuria, refer to BCGuidelines.ca: Microscopic Hematuria.

- LE and/or nitrite are frequently positive in asymptomatic bacteriuria, especially in the elderly.6 Hence, do not order in the elderly if isolated altered mental status, cloudy urine or malodorous urine.7,20

- Sensitivity of urine dipstick testing ranges between 64.3-100% for presence of bacteria with or without pyuria.3 The accuracy of urine dipstick depends on the pretest probability and the population tested.

- In premenopausal women who have a clear presentation of acute cystitis (probability of UTI is high), the urine dipstick is not necessary as a negative dipstick does not rule out infection.3

- Conversely, in women with atypical or unclear symptoms (probability of UTI is < 50%), a positive urine dipstick can support the diagnosis, while a negative urine dipstick can rule out UTI.4

Urine microscopy (also known as microscopic urinalysis)

- Urine microscopy (white blood cells, red blood cells and bacteria) is NOT needed to diagnose a UTI.1,2 If the dipstick is negative, urine microscopy does not provide an advantage over dipstick testing and it is important to reassess the diagnosis.

- Urine microscopy is used to confirm microscopic hematuria in the absence of infection (See BCGuidelines.ca: Microscopic Hematuria) and to investigate parenchymal renal diseases (see Appendix 2).

Urine culture (may include susceptibility results if uropathogen(s) is/are identified)

- A urine culture should be requested in specific circumstances to confirm the diagnosis (if needed) and to guide antibiotic therapy (see Table 2 and Appendix 2).

- This test may be positive due to UTI, asymptomatic bacteriuria or contamination from skin, perineal or gastrointestinal flora.

- If the patient has antibiotic allergies or is being treated with an antibiotic, it is important to document this on the requisition. This may impact the antibiotic susceptibilities reported.

- The organism concentration (i.e. colony count) reported varies by collection type and laboratory. While the threshold of < 105 CFU/mL (100 x 106 CFU/L) has traditionally been used to distinguish growth due to contamination, those with low colony counts may still have infection if they are symptomatic.3 Conversely, asymptomatic patients may have counts > 105 CFU/mL, but treatment may not be warranted (see Table 3).6

- The laboratory workup considers both the number of different bacterial species identified and their respective concentrations. The following can affect the cultures and results:16,17

- Collection from old urinary catheters may produce false positive results from contaminating organisms.

- Improper collection due to contamination with skin, perineal or gastrointestinal flora can produce a false positive result (if the urine was indeed sterile) or a “mixed organisms” result.

- Prolonged storage without refrigeration or preservatives (e.g. boric acid) can produce false positive culture results due to organism overgrowth.

- Antibiotics prior to urine collection can suppress bacterial growth and produce false negative results. This suppression may also permit the growth of flora (e.g. Candida), which are non-contributory to the infection and are misinterpreted as pathogens.

- Profiles of antimicrobial susceptibility testing are available at your local laboratory.

UTI Classification

- For this protocol, UTI is classified as cystitis, where the infection is confined to the bladder, or complicated UTI, with extension outside the bladder (i.e. pyelonephritis and systemic infection) based on Table 1. This definition of complicated UTI may be different than that described in some literature.

Table 1. Symptoms/Signs of UTI used for classification

|

Cystitis18,21,22 |

Complicated UTI (beyond bladder)18,23–25 |

NOT symptoms/signs of UTI in isolation7,20 |

*Note: in older women, new onset dysuria is the most discriminating clinical finding for symptomatic UTI22 |

Symptoms of systemic illness:

|

*Note: the presence of vaginal discharge reduces the probability of UTI by 25%3 |

Diagnosis

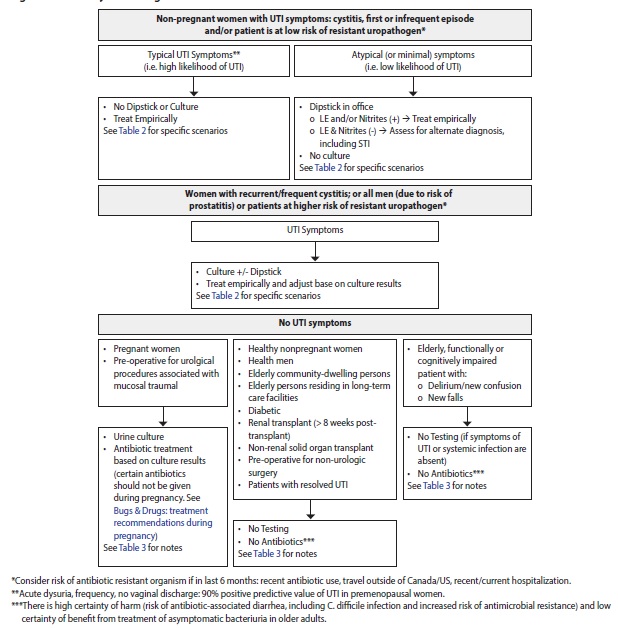

- Symptoms, clinical history, and demographics determine the approach to diagnosis and testing (see Summary in Figure 1 and details in Table 2 and Table 3). If there are symptoms of vaginitis or urethritis, evaluate for other genitourinary infections, including STIs.

Figure 1. Summary of investigations of UTI

Table 2. Approach to diagnosis and investigations of UTI

|

Diagnosis |

Investigations |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

Women with UTI Symptoms |

||

|

Cystitis, first or infrequent episode (≤ 3 per year, expert opinion) Consider risk of antibiotic resistant organisms (ARO) if in last 6 months:5

|

In premenopausal women, the presence of acute dysuria, frequency and no vaginal discharge has a 90% positive predictive value of UTI21 Typical symptoms (i.e. high likelihood of UTI)

Atypical (or minimal) symptoms (i.e. low likelihood of UTI) à Dipstick26

|

Within BC, the most common uropathogens (E.coli) are > 95% susceptible to first line antibiotics.5,27 In non-pregnant women, antibiotic-sparing strategies (i.e. symptomatic management with NSAID28,29, or delayed prescription30,31) can be considered based on patient preference, symptom severity and risk of complications. However, this may result in delayed symptom resolution by a few days and up to 5% increased risk of pyelonephritis.28 If symptoms resolve despite laboratory confirmed resistance and the patient is NOT pregnant, continue antibiotics. However, if the patient is pregnant, change to suitable antibiotics.32 |

|

Cystitis, unresolving or recurring within < 4 weeks after treatment |

Dipstick and urine culture5 |

Consider complicated UTI5 |

|

Cystitis, frequent culture-positive recurrence (> 3 per year, expert opinion)

|

Urine culture5,33 If coitus related:

If non-coitus related:

|

Evaluate for risk factors related to recurrence, and rule out structural or functional abnormalities.33 In patients who remain symptomatic despite prophylactic therapy, consider repeating urine cultures to assess for possible resistance to antimicrobials.35 Do not order routine urine cultures (e.g., monthly) in the absence of symptoms, even in patients with recurrent UTI and/or on prophylactic antibiotics. |

|

Complicated UTI |

Dipstick and urine culture5,18

|

For immunocompromised states (e.g. transplant patients, neutropenia, HIV): If febrile, do blood culture, pre-treatment urine cultures are recommended. Consultation with microbiologist or Infectious Diseases physician recommended for all culture negative recurrent UTI.5 |

|

Men with UTI Symptoms |

||

|

Cystitis, first episode |

Dipstick and urine culture5 If > 50 years old:

|

Consider STI5 |

|

Complicated and recurrent UTI (> 1 UTI), including prostatitis |

Dipstick and urine culture5

|

Consider STI26 For immunocompromised states (e.g. transplant patients, neutropenia, HIV): If febrile, do blood culture, pre-treatment urine cultures are recommended. Consultation with microbiologist or Infectious Diseases physician recommended for all culture negative recurrent UTI.5 |

Table 3. Approach to diagnosis and investigations of asymptomatic bacteriuria

|

Diagnosis |

Investigations |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

Asymptomatic Women and Men |

||

|

Pregnant women (first trimester screening) |

Urine culture 6,36

|

Antibiotic treatment based on culture results, recognizing that certain antibiotics should not be given during pregnancy. See Bugs & Drugs: BugsandDrugs.org: treatment recommendations during pregnancy. |

|

Pre-operative for urological procedures associated with mucosal trauma |

Urine culture prior to procedure6 |

Antibiotic treatment based on culture results, given before procedure6 |

|

No testing required6 |

No antibiotics6,7 For renal transplant patients (< 8 weeks post-transplant) à refer to renal transplant service |

|

Spinal cord injury (including intermittent catheter use) |

No testing required if symptoms of UTI or systemic infection are absent.6 UTI symptoms may be atypical, and include increased spasticity, autonomic dysreflexia, new or worsening urinary incontinence or leakage, a sense of unease with vague back and abdominal pains.37 |

No antibiotics This is a diagnostically challenging group as patients with neurogenic bladders have a high prevalence of bacteriuria and high incidence of UTI. Treatment may be warranted in patients who present with recent onset or change in signs or symptoms in the setting of bacteriuria and pyuria with no alternate diagnosis.6 |

|

Elderly, functionally or cognitively impaired patient with:

|

No testing required if symptoms of UTI or systemic infection are absent.6,7 |

No antibiotics6,7 Before assuming UTI is the cause, assess for other issues with careful observation. Hydrate patient and evaluate for6,7:

There is high certainty of harm (risk of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, including C. difficile infection and increased risk of antimicrobial resistance) and low certainty of benefit from treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in older adults.6 |

|

With indwelling urinary catheter

|

No testing required if symptoms of UTI or systemic infection are absent6,16

If patient is symptomatic, collect urine for culture after removal of old catheter or from a newly inserted catheter.16 |

Catheters can be colonized with bacteria after 24 hours of insertion, and 100% are colonized within 1 month.5,16 |

Management

In non-pregnant women with clinically suspected UTI (cystitis, first or infrequent episode), antibiotic-sparing strategies (i.e. symptomatic management with NSAID 28,29, or delayed prescription 30,31) can be considered based on patient preference, symptom severity and risk of complications. However, this may result in delayed symptom resolution by a few days and up to 5% increased risk of pyelonephritis.28

Treatment resources for the management of urinary tract infections can be found through your local hospital, health authority or laboratory, as well as through the following resources:

Bugs & Drugs® - www.bugsanddrugs.org (This link will only work if IP address is from BC or Alberta)

- This is produced with the support of Alberta Health Services, Alberta Health, the BC Ministry of Health, and the Do Bugs Need Drugs?® program.

- It is available as a webpage and mobile application.

Spectrum Antimicrobials - www.spectrum.md

- This is a commercial product that has been adopted by several Alberta and BC hospitals and health authorities.

- It is available as a webpage and a mobile application.

Empiric fluoroquinolone therapy should be avoided in the treatment of UTIs due to moderate resistance rates and increased risk of adverse events8–10 (hypoglycemia11, tendonitis12, CNS toxicity12, aortic dissection13 and C. difficile infection14).

- Prescribe fluoroquinolone therapy only if the likelihood of resistance is low and the patient has contraindications and/or allergies to other antibiotics.

Publicly available antibiograms include:

- LifeLabs - www.lifelabs.com/healthcare-providers/reports/antibiograms/

- Fraser Health - http://medicalstaff.fraserhealth.ca/Clinical-Resources/#Antimicrobial

- Interior Health – www.interiorhealth.ca/sites/Partners/LabServices/DeptSpecific/microbiology/Pages

/default.aspx - Island Health - https://app.spectrum.md/en/clients/16-island-health (Available with each pathogen)

- Northern Health - https://physicians.northernhealth.ca/physician-resources/clinical-resources/antimicrobial-stewardship-program#about (Available in the Resources and Tools tab)

- Vancouver Coastal Health – www.vhpharmsci.com/PagePocket/index.html (Available in the Anti-Infective Comparison card)

Methodology

These protocol recommendations are tailored to support practice in British Columbia and are based on guidance from the Association of Medical Microbiology, Infectious Disease Canada, the Infectious Diseases Society of America6 and Bugs & Drugs5. Where available, key references are provided. In situations where there is a lack of rigorous evidence, we provide best clinical opinion to support decision making and high-quality patient care. The protocol development process included significant engagement and consultation with primary care providers, specialists and key stakeholders, including Provincial Laboratory Medicine Services. For more information about GPAC protocol development processes, refer to the GPAC handbook available at BCGuidelines.ca.

Resources

Practitioner Resources

- Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada - Asymptomatic bacteriuria in long-term care residents and elderly patients in acute care

- Infectious Diseases Society of America - Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria: 2019 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America

Patient and Caregiver Resources

- HealthLink BC

- Choosing Wisely – Antibiotics for urinary tract infections in older people

References

1. Chen M, Eintracht S, MacNamara E. Successful protocol for eliminating excessive urine microscopies: Quality improvement and cost savings with physician support. Clin Biochem. 2017 Jan;50(1–2):88–93.

2. Point-of-Care Urine Dipstick Testing for Suspected Urinary Tract Infections for Adults: Diagnostic Accuracy. Ottawa: CADTH; 2019 Feb. (CADTH rapid response report: reference list).

3. Chu CM, Lowder JL. Diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infections across age groups. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jul;219(1):40–51.

4. Meister L, Morley EJ, Scheer D, Sinert R. History and Physical Examination Plus Laboratory Testing for the Diagnosis of Adult Female Urinary Tract Infection. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(7):631–45.

5. Bugs & Drugs: Urinary Tract [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: https://bugsanddrugs.org/11637b67-b975-4fbf-bc47-5a559ae6ebf4

6. Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, Colgan R, DeMuri GP, Drekonja D, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria: 2019 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2019 Mar 21;

7. Blondel-Hill E, Patrick D, Nott C, Abbass K, Lau TT, German G. AMMI Canada position statement on asymptomatic bacteriuria. Off J Assoc Med Microbiol Infect Dis Can [Internet]. 2018 Mar 12 [cited 2019 Jan 25]; Available from: https://jammi.utpjournals.press/doi/abs/10.3138/jammi.3.1.02

8. Quinolone- and fluoroquinolone-containing medicinal products [Internet]. European Medicines Agency. 2018 [cited 2019 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/quinolone-fluoroquinolone-containing-medicinal-products

9. Government of Canada HC. Information Update - Fluoroquinolone antibiotics may, in rare cases, cause persistent disabling side effects [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Jun 14]. Available from: https://healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall-alert-rappel-avis/hc-sc/2017/61920a-eng.php

10. George Sakoulas MD. Adverse Effects of Fluoroquinolones: Where Do We Stand? NEJM J Watch [Internet]. 2019 Feb 13 [cited 2019 Jun 14];2019. Available from: https://www.jwatch.org/NA48248/2019/02/13/adverse-effects-fluoroquinolones-where-do-we-stand

11. FDA reinforces safety information about serious low blood sugar levels and mental health side effects with fluoroquinolone antibiotics; requires label changes. [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-reinforces-safety-information-about-serious-low-blood-sugar-levels-and-mental-health-side

12. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA updates warnings for oral and injectable fluoroquinolone antibiotics due to disabling side effects. [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-updates-warnings-oral-and-injectable-fluoroquinolone-antibiotics

13. FDA warns about increased risk of ruptures or tears in the aorta blood vessel with fluoroquinolone antibiotics in certain patients. [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-warns-about-increased-risk-ruptures-or-tears-aorta-blood-vessel-fluoroquinolone-antibiotics

14. Pépin J, Saheb N, Coulombe M-A, Alary M-E, Corriveau M-P, Authier S, et al. Emergence of Fluoroquinolones as the Predominant Risk Factor for Clostridium difficile–Associated Diarrhea: A Cohort Study during an Epidemic in Quebec. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Nov 1;41(9):1254–60.

15. Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in the Elderly. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1997 Sep 1;11(3):647–62.

16. Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC, et al. Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection in Adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Mar 1;50(5):625–63.

17. Mundt LA, Shanahan K. Graff’s Textbook of Routine Urinalysis and Body Fluids. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. 352 p.

18. G. Bonkat (chair), R.R. Bartoletti, F. Bruyère, T. Cai, S.E. Geerlings, B. Köves, S. Schubert, F. Wagenlehner, Guidelines Associates: T. Mezei, A. Pilatz, B. Pradere, R. Veeratterapillay. Urological Infections, European Association of Urology [Internet]. Uroweb. [cited 2019 Apr 29]. Available from: https://uroweb.org/guideline/urological-infections/

19. Simerville JA, Maxted WC, Pahira JJ. Urinalysis: A Comprehensive Review. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Mar 15;71(6):1153–62.

20. Schulz L, Hoffman RJ, Pothof J, Fox B. Top Ten Myths Regarding the Diagnosis and Treatment of Urinary Tract Infections. J Emerg Med. 2016 Jul;51(1):25–30.

21. Bent S, Nallamothu BK, Simel DL, Fihn SD, Saint S. Does this woman have an acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection? JAMA. 2002 May 22;287(20):2701–10.

22. Mody L, Juthani-Mehta M. Urinary Tract Infections in Older Women. JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;311(8):844–54.

23. Fairley KF, Carson NE, Gutch RC, Leighton P, Grounds AD, Laird EC, et al. Site of infection in acute urinary-tract infection in general practice. The Lancet. 1971 Sep 18;298(7725):615–8.

24. Colgan R, Williams M, Johnson JR. Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Pyelonephritis in Women. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Sep 1;84(5):519–26.

25. Michels TC, Sands JE. Dysuria: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis in Adults. Am Fam Physician. 2015 Nov 1;92(9):778–86.

26. SIGN 88 Management of suspected bacterial urinary tract infection in adults [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5582677/

27. Antibiograms – LifeLabs [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: /healthcare-providers/reports/antibiograms/

28. Kronenberg A, Bütikofer L, Odutayo A, Mühlemann K, Costa BR da, Battaglia M, et al. Symptomatic treatment of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections in the ambulatory setting: randomised, double blind trial. BMJ. 2017 Nov 8;359:j4784.

29. Gágyor I, Bleidorn J, Kochen MM, Schmiemann G, Wegscheider K, Hummers-Pradier E. Ibuprofen versus fosfomycin for uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2015 Dec 23;351:h6544.

30. Little P, Moore MV, Turner S, Rumsby K, Warner G, Lowes JA, et al. Effectiveness of five different approaches in management of urinary tract infection: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010 Feb 5;340:c199.

31. Knottnerus BJ, Geerlings SE, van Charante EPM, ter Riet G. Women with symptoms of uncomplicated urinary tract infection are often willing to delay antibiotic treatment: a prospective cohort study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013 May 31;14:71.

32. Summary of the evidence: Urinary tract infection (lower): antimicrobial prescribing. NICE [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 15]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng109/chapter/Summary-of-the-evidence

33. Dason S, Dason JT, Kapoor A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of recurrent urinary tract infection in women. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011 Oct;5(5):316–22.

34. Albert X, Huertas I, Pereiró II, Sanfélix J, Gosalbes V, Perrota C. Antibiotics for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD001209.

35. Arnold JJ, Hehn LE, Klein DA. Common Questions About Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Women. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Apr 1;93(7):560–9.

36. Moore A, Doull M, Grad R, Groulx S, Pottie K, Tonelli M, et al. Recommendations on screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. CMAJ. 2018 Jul 9;190(27):E823–30.

37. Jahromi MS, Mure A, Gomez CS. UTIs in Patients with Neurogenic Bladder. Curr Urol Rep. 2014 Aug 12;15(9):433.

Abbreviations

ARO Antibiotic Resistant Organisms

LE Leukocyte Esterase

PVR Post-Void Residual

STI Sexually Transmitted Infection

UTI Urinary Tract Infection

This protocol is based on scientific evidence current as of the effective date.

The protocol was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee in collaboration with Provincial Laboratory Medicine Services and adopted by the Medical Services Commission.

For more information about how BC Guidelines are developed, refer to the GPAC Handbook available at

BCGuidelines.ca: GPAC Handbook.

THE GUIDELINES AND PROTOCOLS ADVISORY COMMITTEE

|

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

Contact Information: Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee PO Box 9642 STN PROV GOVT Victoria, BC V8W 9P1 Email: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca Website: www.BCGuidelines.ca Disclaimer The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the guidelines) have been developed by the guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional. |

Appendix 1 – Point of care urine collection prior to urine culture1

Urine Collection

Upon rising or at any time, collect urine in the C&S container provided.

- Wash and dry hands.

- Begin urinating into the toilet. Without stopping the flow of urine, place the container in the urine stream to collect some urine and remove the container before the urine stops flowing.

- Close the container tightly, taking care not to touch the rim or the inside of the container with your fingers.

Labelling:

- Label the container with your name, date of birth, and the date of collection.

Packaging:

- Place the container in the bag provided and securely close the bag.

- Fold any paperwork and place in the external pocket of the specimen transport bag.

- This ensures the specimen will not leak onto the paperwork.

Storage and Transport:

- Refrigerate and bring specimen to the laboratory within one hour of collection.

References:

Patient Test Instructions – LifeLabs [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 2]. Available from: www.lifelabs.com/patients/preparing-for-a-test/patient-test-instructions/

Appendix 2 - Interpretation of urine testing results reported by laboratories in BC1,2

|

Finding |

Positive result indicates1,2 |

|

Urine Dipstick |

|

|

Specific Gravity |

Indicates relative hydration/dehydration. |

|

pH |

Alkaline urine suggests presence of urea-splitting organism. |

|

Leukocytes, white blood cells, pyuria |

Measured by Leukocyte Esterase. Dipstick is positive in the presence of > 5-15 WBC/high-power field. |

|

Nitrite |

Detects presence of certain bacteria that convert nitrates into nitrites. Dipstick is positive when bacteria > 105 CFU/mL. |

|

Protein |

Proteinuria is defined as 10-20 mg per dL. 1+ = approximately 30 mg protein per dL 2+ = 100 mg per dL 3+ = 300 mg per dL 4+= 10000 mg per dL |

|

Glucose |

Presence indicates glycosuria. |

|

Ketones |

Measured by acetic acid. Presence indicates ketonuria. |

|

Blood |

Detects presence of hemoglobin. Urine dipsticks can detect low levels of blood in urine (correlates with > 1-4 RBC/high-power field). |

|

Urine Microscopy |

|

|

Red Blood Cells (RBCs) |

Urinary tract inflammation or glomerular bleeding (0-2 RBC/high power field (hpf) normal value, ≥3 RBC/hpf significant for microscopic hematuria). For a list of other causes, see Urinalysis: A Comprehensive Review.19 In the case of isolated microscopic hematuria, refer to BCGuidelines.ca: Microscopic Hematuria. |

|

White Blood Cells (WBCs) |

Infection, interstitial nephritis. |

|

Hyaline casts |

Normal when found absence of other casts. |

|

Granular casts |

Acute tubular necrosis (ATN). |

|

RBC casts |

Glomerulonephritis. |

|

WBC casts |

Acute interstitial nephritis or pyelonephritis. |

|

Waxy casts |

Non-specific, acute or chronic kidney impairment. |

|

Fatty casts |

Marked proteinuria or nephrotic syndromes. |

|

Renal tubular epithelial cells |

Acute tubular necrosis (ATN). |

|

Bacteria |

Infection, contamination and/or overgrowth. |

|

Schistosome ova/miracidia |

Detection of Schistosoma haematobium requires a special request. |

|

Urate or other crystals |

Interpret based on crystal found. |

|

Urine Culture |

|

|

Organism(s) |

The report only includes organisms suspected to be uropathogens (e.g. E. coli). This depends on patient demographics, concentration (i.e. colony count) of the specific organism(s) and the specific laboratory protocol. In urine with multiple (or mixed) organisms, identification may not be performed as it may produce misleading results that are not related to the UTI. |

|

Antibiotic susceptibilities |

The report only includes antibiotics that can be used for UTI. The specific antibiotics listed depend on the patient demographics, documented antibiotics and allergies, organism(s) identified, colony count of the organism(s) and the specific laboratory protocol. |

References:

- Chu CM, Lowder JL. Diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infections across age groups. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jul;219(1):40–51.

- Simerville JA, Maxted WC, Pahira JJ. Urinalysis: A Comprehensive Review. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Mar 15;71(6):1153–62

TOP

TOP