Cobalamin (vitamin B12) and Folate Deficiency

Revised Date: January 18, 2023

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Background

- Epidemiology

- Patient Risk Factors Associated with B12 Deficiency

- Patient Risk Factors Associated with Folate Deficiency

- Prevention

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Ongoing Care

- References

- Resources

- Appendix A: Dietary sources of cobalamin

Scope

This guideline covers the primary care investigation and management of cobalamin (vitamin B12 or simply B12) and folate deficiency in adults. This guideline outlines the indications for B12 testing and discusses an observed increase in B12 testing in BC. Specifically:

- Outpatient and inpatient laboratory test volumes for B12 investigations increased from 267,721 to 570,265 between 2013 and 2020. This resulted in an increase in annual B12 testing expenditure from $3.0 million to $5.6 million during the same time period.

- On average, 420,303 tests cost $4.4 million per year.

- Patients ³ 65 years of age accounted for the majority (37%) of B12 test volumes in 2019.

- Female patients account for 62% of annual test volumes while males account for 38%.

Key Recommendations

- Routine B12 screening and testing in asymptomatic patients is not supported by evidence.

- Consider B12 supplementation without testing in asymptomatic patients with risk factors for B12 deficiency (see Table 1: Patient Risk Factors Associated with B12 Deficiency). Patients can call 8-1-1 to speak with a HealthLink BC registered dietitian.

- B12 deficiency can cause preventable permanent injury and should be considered with new onset neurological conditions and symptoms suggestive of B12 deficiency (See Low B12 symptoms section below).

- Folate testing is rarely indicated but may be available via consultation with the laboratory medicine physician or scientist.

- Folate deficiency in pregnancy is associated with preventable and serious fetal harm, i.e., neural tube defects (NTD). Folic acid supplementation is recommended during pregnancy.

- A daily multivitamin containing B12 and folic acid is recommended for all people who could become pregnant, especially those with a vegan diet.

Background

The terms cobalamin (cyanocobalamin) and vitamin B12 can be used interchangeably. B12 will be used throughout this guideline. A 2022 CADTH review1 performed at the request of GPAC found:

- No studies evaluating the clinical utility of B12 testing in people with suspected B12 deficiency.

- No studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of B12 testing in people with suspected B12 deficiency.

- No evidence-based guidelines regarding the use of B12 testing in people with suspected B12 deficiency.

No relevant literature was identified regarding the diagnostic test accuracy, clinical utility, and cost-effectiveness of serum folate testing in people with suspected folate deficiency.

Vitamin B12

B12 is a water-soluble vitamin found in foods derived from animal products and from fortified foods.2 (see HealthLink BC’s page on Quick Nutrition Check for Vitamin B12 for dietary information).The prevalence of B12 deficiency in the general population differs between older and younger people. For example, 6% of those < 60 years in the United Kingdom were found to be B12 deficient, compared to 20% of those ≥ 60 years. B12 deficiency also correlates to geographic location and ethnic background (e.g., 6% of those in the United States were found to be B12 deficient, compared to 40% in Latin American countries and 70% in East Indian adults. Most cases of B12 3 deficiency in high-income countries are attributable to malabsorptive disorders. A specific form of malabsorption, pernicious anemia, is caused by autoimmunity to intrinsic factor resulting in failure to absorb dietary B12. Other causes for malabsorption include Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, and medication interactions (e.g., proton pump inhibitor, metformin). A rare but serious form of B12 deficiency can arise from the protracted use of nitrous oxide (N20) as a recreational inhalant. Vitamin B12 deficiency may also be caused by diet (e.g., vegan diet, breastfed neonates born to B12 deficient mothers).1

As vitamin B12 is stored in body tissue, mainly the liver, sub-clinical deficiency from dietary deficiency alone develops over the course of several years (e.g., 5-10 years).4 Manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency may be mild, such as fatigue and heart palpitations, but may progress to neurological manifestations, including peripheral neuropathy and dementia-like symptoms. 5

There is currently no agreed upon reference standard for measuring B12, and all are susceptible to confounding factors. A lack of agreement around cut-off levels (i.e., thresholds) to diagnose deficiency adds another layer of difficulty in diagnosing deficiency, as these thresholds may differ.1

Low B12 Symptoms: Patients may present with any of the following (specific or red flag symptoms in Bold):

- Neurologic abnormalities associated with impaired nerve function and demyelination, including new onset and otherwise unexplained central nervous system symptoms (e.g., cognitive impairment), motor and/or sensory neuropathy, and subacute combined degeneration of the dorsal and lateral columns of the spinal cord4 (e.g., symmetric paresthesias, numbness, gait disorder, positive Babinski and exaggerated patellar reflex).

- Glossitis (including pain, swelling, tenderness, and loss of papillae of the tongue), and/or chronic (>3 months) unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., pain or diarrhea), reflecting impaired regeneration of epithelial cells.

- Worsening macrocytic anemia: B12 deficiency may also cause a macrocytic (megaloblastic) anemia BUT, in the presence of folate supplementation, this anemia may be masked so that B12 deficiency may present with exclusively neurologic features. Therefore, in patients with neurologic symptoms do not rely on the complete blood cell count (CBC) to help rule in or out B12 deficiency.

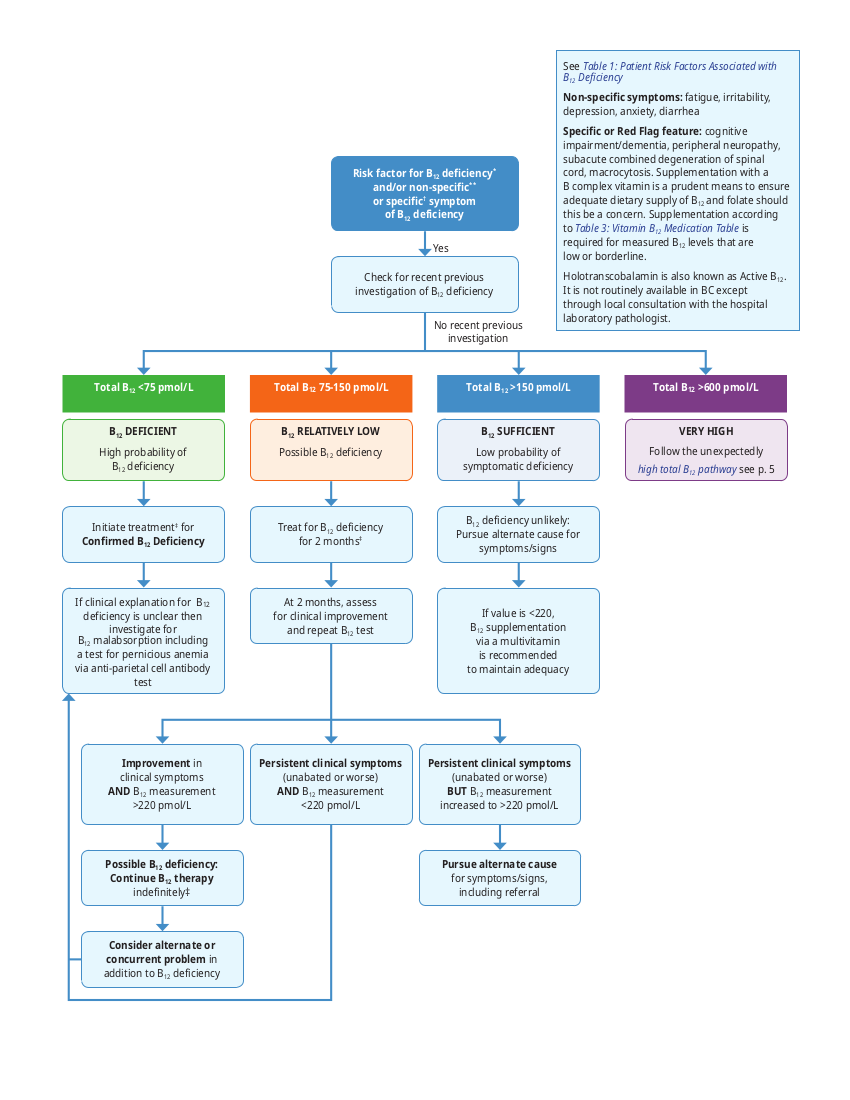

- If a patient has specific or red flag features B12 deficiency testing should be initiated (see Figure 1: B12 Test Result Review and Process Algorithm for Patients with Risk Factor for B12 Deficiency* and/or Non-specific** or Specific† Symptom of B12 Deficiency).

Folate

Folate is found in dark green vegetables, legumes (i.e. peas, beans and lentils), and citrus fruit (see HealthLink BC’s page on Getting Enough Folic Acid (Folate) for dietary information).2, 6 Mandatory folic acid fortification of foods (i.e. white flour, enriched pasta and cornmeal) was implemented in Canada in 1998.6 This was associated with a significant increase in average population folate levels, and folate deficiency is now rare in Canada. Two outpatient laboratories in BC reported > 99% of folate tests were normal in 2010.

In rare cases, folate deficiency is associated with megaloblastic anemia and birth defects, especially neural tube defects, in children born to mothers with folate deficiency.7

Epidemiology

Between 2019 and 2021, 2.17 million B12 tests were performed for 1.39 million patients in BC. Approximately 33% of patients had two or more tests during this time period. Nine percent of all B12 tests had an abnormal result. The cost of a B12 test in BC is $14.38.

Patient Risk Factors Associated with B12 Deficiency

There is no evidence to support regular B12 screening for asymptomatic patients. In asymptomatic patients with risk factors (see Table 1: Patient Risk Factors Associated with B12 Deficiency below) consider supplementation in lieu of testing.

Table 1: Patient Risk Factors Associated with B12 Deficiency

Bold represents factors associated with more rapid onset of clinical symptoms i.e., within 5 years. Non-bold represents slower contributing factors (e.g., 5 to 10 years). Refer to Table 3: Treatment of B12 deficiency for supplementation routes, dosage and duration.

| Factor | B12 Deficiency |

|---|---|

| Medications |

• Histamine 2 (H2) receptor antagonists4, 8, 9 * |

| Factors contributing to inadequate intake |

• Low intake of B12 rich foods4, 10 |

| Decreased Ileal Absorption |

• Gastric/bariatric surgery4, 8, 10 |

| Decreased Intrinsic Factor |

• Atrophic gastritis10 |

* Vitamin B12 deficiency is associated with either long-term proton inhibitor (PPI) or Histamine-2 receptor blocker (H2 blocker) use, but a causal relationship is not established.20

Patient Risk Factors Associated with Folate Deficiency

There is no evidence to support regular folate screening for asymptomatic patients. Consider supplementation in asymptomatic patients with risk factors (see Table 2: Patient Risk Factors Associated with Folate Deficiency below) consider supplementation. Refer to Table 6: Treatment of folate deficiency for supplementation routes, dosage and duration.

Table 2: Patient Risk Factors Associated with Folate Deficiency

| Folate Deficiency Patient Risk Factors |

|---|

|

Prevention

Prevention of B12 Deficiency

B12 is present in many animal products e.g., dairy products, and eggs; therefore, a typical non-vegetarian diet contains adequate B12. Practitioners should consider specific B12 dietary counselling for patients currently on a vegetarian, or vegan diet, including patients who have recently initiated such a diet. To help prevent B12 deficiency, encourage all individuals to consume a diet with sufficient B12. Consider a dietitian referral for patients to call 8-1-1 to speak with a HealthLink BC dietitian. With respect to B12 supplementation:

- Consider supplementation when patients adhere to a vegan or strict vegetarian diet.

- Consider supplementation when the patient has risk factors associated with B12 Deficiency as described in see Table 1: Patient Risk Factors Associated with B12 Deficiency above.

- Doses usually used in supplementation16 are not associated with harm.7 (See Table 3: B12 Medication Table below).

- Oral supplements are available over the counter in various doses and dosage forms. (Prices vary).

- Some PharmaCare plans provide coverage for select oral and parenteral formulations (1000 micrograms [mcg]/mL).

Prevention of Folate Deficiency

It is recommended that all people who could become pregnant take a daily supplement containing 400 mcg/0.4mg folic acid to reduce the risk of neural tube defects (NTDs).22 This is most easily obtained through a prenatal vitamin.23

- Supplementation of 1 mg daily is recommended for patients with specific risk factors (e.g., bariatric/gastric surgery patients, those with severe malnutrition, chronic alcohol use, chronic hemolytic anemia and conditions with high cell turnover, and use of antimetabolite medications such as methotrexate).21

- The doses of folic acid used in supplementation (see Table 5: Folic Acid Medication Table below) are non-toxic and are not associated with harm.21, 23 Consider supplementation when the patient is prescribed medications causing folate deficiency, e.g., methotrexate.8

- Over the counter folate products include: 400 mcg/0.4 mg and 1 mg tablets.†

- Prescription folate products covered by PharmaCare‡ include: 5 mg tablets and 5 mg/mL injection.

Diagnosis

B12 Testing

Routine B12 screening is not supported by the current body of evidence. The test has the following limitations:

- Levels of B12 do not correlate well with clinical symptoms. Elderly patients may have normal B12 levels with clinically significant B12 deficiency.

- Women taking oral contraceptives may have decreased serum B12 levels in the absence of clinical deficiency (due to decreases in the B12 carrier protein, haptocorrin).

- There is a large ‘indeterminate zone’ between normal and abnormal levels (see Figure1: B12 Test Result Review and Process Algorithm for Patients with Risk Factor for B12 Deficiency* and/or Non- Specific** or Specific† Symptom of B12 Deficiency below).

- The reference intervals may vary between laboratories. The conventional cut-off for serum B12 deficiency varies from 150-220 pmol/L.24

In a clinically symptomatic patient with specific features of B12 deficiency, order a B12 test, see Figure1: B12 Test Result Review and Process Algorithm for Patients with Risk Factor for B12 Deficiency* and/or Non- Specific** or Specific† Symptom of B12 Deficiency for more detail. Refer to Perinatal Services BC's (PSBC) website for the Early Prenatal Care Summary and Checklist for Primary Care Providers.

Asymptomatic: In asymptomatic patients with risk factors (see Table 1: Patient Risk Factors Associated with B12 Deficiency above) consider supplementation in lieu of testing.

High total B12 pathway:

If the B12 level is above the upper limit of normal, follow up should be organized as follows:

- Was the patient already taking B12? If yes, decrease the dose. If no, go to step ii.

- Does the patient have end stage renal disease? If yes, no specific follow up for B12 is required. If no, go to step iii.

- Are there clinical features of liver disease, myeloproliferative disorder (e.g., blood film changes of unexplained cytopenia, thrombocytosis, or leukocytosis), or another cancer (e.g., cachexia, constitutional symptoms – fever, weight loss, night sweats)? If yes, refer to the appropriate specialist depending on symptoms. If no, go to step iv.

- Verify that the elevated B12 test result is not in error due to test interference (e.g., macroB12 or heterophile antibody interference) by ordering another test (e.g., total homocysteine). If total homocysteine is normal, this corroborates the B12 result. If the total homocysteine is elevated, contact the laboratory pathologist to facilitate further investigations.25

Repeat Testing:

Repeat testing of B12 may be warranted after a trial of therapy or as an assessment of adherence. Repeat testing should wait at least 2 months after therapy has been started.26 If the B12 is normal (rare probability of B12 deficiency – see Table 3: B12 Medication Table), a repeat investigation is not required in the absence of new signs of disease. In absence of a reversible factor therapy, supplementation in most cases is lifelong.

Folate Testing

Serum folate and red blood cell (RBC) folate testing is no longer offered in BC.

In cases of unexplained macrocytic anemia associated with high homocysteine levels and normal B12 testing results, folate testing may be arranged if supported by laboratory specialist consultation. Refer to Table 2: Patient Risk Factors Associated with Folate Deficiency for more information.

If folate deficiency is suspected, it is reasonable to give oral folic acid (0.4 – 1 mg/day) without doing laboratory investigation for deficiency at least until the hemoglobin and mean corpuscular volume normalizes (or longer if the underlying cause cannot be eliminated).

Figure 1: B12 Test Result Review and Process Algorithm for Patients with Risk Factor for B12 Deficiency* and/or Non-specific** or Specific† Symptom of B12 Deficiency

Management

Treatment

In suspected B12 deficiency, supplement both B12 and folate.23, 27

Vitamin B12

Early treatment of B12 deficiency is particularly important because neurologic symptoms may be irreversible. Oral administration is extremely effective and less invasive compared to other routes. For selected symptomatic patients please review Figure 1: B12 Test Result Review and Process Algorithm for Patients with Risk Factor for B12 Deficiency* and/or Non-specific** or Specific† Symptom of B12Deficiency.

Table 3: Vitamin B12 Medication Table

The table below is not an exhaustive list of all vitamin B12 products and therapeutic considerations.

| Product Dosage Forms and Strengths | Recommended Adult Dose | Approx. Cost per month† | PharmaCare Coverage‡ | Therapeutic considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

cyanocobalamin Oral/sublingual tablets: 250, 500, 1000, Liquid: 200 mcg/mL |

500 - 2000 mcg PO daily* pernicious anemia: 1000 mcg po dailyb food-cobalamin malabsorption: 250 mcg po dailyb |

$5 - 10 | Regular benefit (Plan W): 250, 1000 mcg tablets |

|

| Injection (IM or subcut): 1000 mcg/mL |

Initial: 1000mcg IM/subcut dailt for Maintenance: 1000 mcg IM/subcut monthly |

$5 | Regular benefit: 1000 mcg/mL |

|

|

methylcobalamin Tablets: 1000, 2500, 5000 mcg |

500 - 2000 mcg PO dailya | $5 - 10 | Regular benefit (Plan W): 1000 mcg tablet |

|

† Cost of generic without mark-up or professional fee rounded up to nearest $5; calculated from McKesson Canada https://www.mckesson.ca/ (Accessed February 17, 2022)

‡ Coverage is subject to drug price limits set by PharmaCare and to the patient’s PharmaCare plan rules and deductibles. See https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/ health-drug-coverage/pharmacare-for-bc-residents and https://pharmacareformularysearch.gov.bc.ca/.

Note: For complete details, please review product monographs at https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/index-eng.jsp and regularly review current Health Canada advisories, warnings and recalls at: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/media/advisories-avis/index_e.html for the most up to date information.)

Table 4: Treatment of B12 deficiency (adapted from Means 2021)27

| Demographic | Route of administration | Dosage and frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Adults with normal absorption | Oral | 1000 mcg orally once per day. |

| Adults with impaired absorption | Oral | Therapy with very high oral doses of oral vitamin B12 (e.g., 1000 to 2000 mcgg daily) will be effective if the dose is high enough to provide absorption via a mechanism that does not require intrinsic factor or a functioning terminal ileum (i.e., passive diffusion/mass action). |

| Adults with dietary deficiency | Oral | Individuals with diets that lack vitamin B12 (e.g., vegans, vegetarians, infants exclusively breastfed by vitamin B12- deficient mothers) are expected to have normal absorption via the oral route and can be treated with oral supplements that provide the recommended amount (500-2000 mcg). |

| Adults with pernicious anemia | Intramuscular** or deep subcutaneous injection High-dose oral vitamin B12 |

Parental vitamin B12 at an initial dose of 1000 mcg (1mg) once per week for four weeks, followed by 1000 mcg once per month. 1000 to 2000 mcg (1 to 2mg) daily (provided there are no acute symptoms of anemia or neurologic complications and adherence is assured). |

| Adults with altered gastrointestinal anatomy | Parenteral | If the alteration is permanent, then indefinite treatment with parenteral vitamin B12 is usually appropriate. If the alteration is reversed, then therapy may be discontinued, although it is reasonable to check the vitamin B12 level several months after stopping therapy. Check B12 level three or four times during the first year of therapy. |

| Adults with symptomatic anemia, neurologic or neuro-psychiatric findings, or pregnancy | Parenteral Oral |

1000 mcg of vitamin B12 every other day initially for approximately two weeks, followed by administration once monthly (cyanocobalamin). Once the initial deficiency has been corrected, an oral trial is reasonable, based on patient preference and adequate B12 levels. |

Note: Intranasal administration is generally not used. Transdermal forms of vitamin B12 are available over the counter, but this route of administration has not been validated clinically in the setting of vitamin B12 deficiency and should not be relied upon for treatment.

** “Individuals treated with parenteral vitamin B12 can be taught to self-administer the injections, often with good results, minimal to no pain, and lower costs than office-based injection.”27

Folate treatment

Refer to Table 6: Treatment of folate deficiency below for folate deficiency treatment options and the SOGC Guideline No. 427: Folic Acid and Multivitamin Supplementation for Prevention of Folic Acid-Sensitive Congenital Anomalies for more information.

Table 5: Folic Acid Medication Table

The table below is not an exhaustive list of all folic acid products and therapeutic considerations.

| Product Dosage Forms and Strenghts | Recommended Adult Dose | Approx. Cost per month† | PharmaCare Coverage‡ | Therapeutic Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| folic acid Tablets: 04.4, 1, 5 mg |

1 - 5 mg PO dailyf | $5 | Regular benefit: 1 mg (Plan W only), 5 mg tablets |

|

| Injection (IM, subcut): 5mg/mL | 0.4 - 1 mg IM/subcut dailyf | $25 | Non-benefit | Allergic reactions (erythrma, pruritus and/or urticaria) are rareg |

† Cost of generic without mark-up or professional fee rounded up to nearest $5; calculated from McKesson Canada https://www.mckesson.ca/ (Accessed February 17, 2022)

‡ Coverage is subject to drug price limits set by PharmaCare and to the patient’s PharmaCare plan rules and deductibles. See https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/ health-drug-coverage/pharmacare-for-bc-residents and https://pharmacareformularysearch.gov.bc.ca/.

Note: For complete details, please review product monographs at https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/index-eng.jsp and regularly review current Health Canada advisories, warnings and recalls at: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/media/advisories-avis/index_e.html for the most up to date information.

References:

- Vitamin B12 CPhA Monograph. e-CPS. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Pharmacists Association. Accessed online February 17, 2022.

- Andres E, Dali-Youcef N, Serraj K et al. Oral cobalamin (vitamin B12) treatment. An update. Int Jnl Lab Hem 2009;31:1-8.

- Vidal-Alaball J, Butler C, Cannings-John R et al. Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. ; (3): CD004655. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004655.pub2.

- Sharabi A, Cohen E, Sulkes J, et al. Replacement therapy for vitamin B12 deficiency: comparison between the submingual and oral route. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2003;56(6):635-638.

- Obeid R, Fedosov SN, Nexo E. Cobalamin coenzyme forms are not likely to be superior to cyano- and hydroxyl-cobalamin in prevention or treatment of cobalamin deficiency. Mol Nutr Food Res 2015;59:1364-1372.

- Folic Acid: Drug information. UpToDate. Waltham WA: UpToDate Inc. Accessed online February 17, 2022.

- Folic Acid CPhA Monograph. e-CPS. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Pharmacists Association. Accessed online February 17, 2022.

Table 6: Treatment of folate deficiency (adapted from Means 2021)27

| Demographic | Route of administration | Dosage and frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals with reversible cause of deficiency | Oral | 1 to 5 mg daily given for one to four months or until there is laboratory evidence of hematologic and/or neurologic worsening occur). |

| Individuals with chronic cause of deficiency | Oral | 1 to 5 mg daily, may be indefinitely (some advocate repeat testing for vitamin B12 deficiency in patients receiving long-term folic acide, especially if hematologic and/or neurologic worsening occur). |

| Individuals who are unable to take an oral medication (e.g., due to vomiting) or those who have severe or symptomatic anemia due to folate deficiency and hence have a more urgent need for rapid correction | Intravenous | 1 to 5 mg daily |

Ongoing Care

Ongoing Management

Vitamin B12

Duration of therapy

Once a diagnosis of B12 deficiency due to poor absorption of B12 has been made, therapy should be maintained lifelong.25

Folate

Duration of therapy

Patients with pernicious anemia require lifelong therapy, while patients with malabsorption require treatment until underlying condition or diet is corrected.27

Monitoring

Increased clinical surveillance is suggested for patients with non-nutritional folate folate deficiency.27

Quality Check Point

To help practitioners review their own practice, some relevant measures have been included below. These measures may be obtained using your Electronic Medical Records (EMR) or with assistance from the Health Data Coalition:

- % patients on B12

- % patients on folate

- % active patients with B12 test in last year

- % active patients with folate test in last year

- % pregnant patients on folate/B12

This process would count towards Mainpro+ credits or College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia (CPSBC) accreditation processes.

References

- Hamel C, Spry C. Vitamin B12 Testing in People With Suspected Vitamin B12 Deficiency. Can J Health Technol [Internet]. 2022 Mar 24 [cited 2022 Apr 7];2(3). Available from: http://canjhealthtechnol.ca/index.php/cjht/article/view/rc1413

- Health Canada. Foods to which vitamins, mineral nutrients and amino acids may or must be added [D.03.002, FDR] [Internet]. Health Canada; 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 4]. Available from: https://inspection.canada.ca/food-labels/labelling/industry/nutrient-content/reference-information/ eng/1389908857542/1389908896254?chap=1

- Langan RC, Goodbred AJ. Vitamin B12 Deficiency: Recognition and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Sep 15;96(6):384–9.

- Means R, Fairfield K. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of vitamin B12 andfolate deficiency. Date [Internet]. 2021 Mar 26; Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-vitamin-b12-and-folate-deficiency?search=Clinical%20manifestations%20and%20 diagnosis%20of%20vitamin%20B12%20andfolate%20deficiency&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Vitamin B12 & Health. Vitamin B12 and health: vitamin B12 deficiency test [Internet]. Vitamin B12 & Health; [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.b12-vitamin.com/deficiency-test/

- Health Canada. Folate [Internet]. Health Canada; 2012 [cited 2022 Sep 10]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food- nutrition-surveillance/health-nutrition-surveys/canadian-health-measures-survey/folate-nutrition-biomarkers-cycle-1-canadian-health-measures-survey-food- nutrition-surveillance-health-canada.html

- Wilson RD, Audibert F, Brock JA, Carroll J, Cartier L, Gagnon A, et al. Pre-conception Folic Acid and Multivitamin Supplementation for the Primary and Secondary Prevention of Neural Tube Defects and Other Folic Acid-Sensitive Congenital Anomalies. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015 Jun;37(6):534–49.

- Green R, Allen LH, Bjørke-Monsen AL, Brito A, Guéant JL, Miller JW, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2017 Dec 21;3(1):17040.

- Oh R. Vitamin B12 deficiency [Internet]. BMJ Best Practice; 2021 [cited 2021 Dec 20]. Available from: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/822

- Means R, Fairfield K. Causes and pathophysiology of vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies. Date [Internet]. 2019 Nov 22 [cited 2021 Dec 1]; Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-vitamin-b12-and-folate-deficiency?search=vitamin+b12+deficiency&source=sear ch_result&selectedTitle=1%7E150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Anastasi L, Jacobsen J, Nicolopoulos K, Rochet E, Foerster V, Vreugdenburg T. Effectiveness and safety of vitamin B12 tests [Internet]. Switzerland Federal Office of Public Health; 2021 [cited 2021 Dec 1]. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/versicherungen/krankenversicherung/krankenversicherung- leistungen-tarife/hta/hta-projekte/vitaminb12tests.html

- Infante M, Leoni M, Caprio M, Fabbri A. Long-term metformin therapy and vitamin B12 deficiency: an association to bear in mind. World J Diabetes. 2021 Jul 15;12(7):916–31.

- Chapman LE, Darling AL, Brown JE. Association between metformin and vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Diabetes Metab. 2016 Nov;42(5):316–27.

- Linnebank M, Moskau S, Semmler A, Widman G, Stoffel-Wagner B, Weller M, et al. Antiepileptic drugs interact with folate and vitamin B12 serum levels. Ann Neurol. 2011 Feb;69(2):352–9.

- Quay TAW, Schroder TH, Jeruszka-Bielak M, Li W, Devlin AM, Barr SI, et al. High prevalence of suboptimal vitamin B12 status in young adult women of South Asian and European ethnicity. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2015 Dec;40(12):1279–86.

- Schroder TH, Sinclair G, Mattman A, Jung B, Barr SI, Vallance HD, et al. Pregnant women of South Asian ethnicity in Canada have substantially lower vitamin B12 status compared with pregnant women of European ethnicity. Br J Nutr. 2017 Sep 28;118(6):454–62.

- Jeruszka-Bielak M, Isman C, Schroder T, Li W, Green T, Lamers Y. South Asian Ethnicity Is Related to the Highest Risk of Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Pregnant Canadian Women. Nutrients. 2017 Mar 23;9(4):317.

- Hasbaoui BE, Mebrouk N, Saghir S, Yajouri AE, Abilkassem R, Agadr A. Vitamin B12 deficiency: case report and review of literature. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38:237.

- Ward MG, Kariyawasam VC, Mogan SB, Patel KV, Pantelidou M, Sobczyńska-Malefora A, et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Functional Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Patients with Crohnʼs Disease: Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Dec;21(12):2839–47.

- Dela Cruz MT, Patel S, Ngo L, Sullivan K. Does long-term use of proton pump inhibitors cause vitamin B12 deficiency? Evid-Based Pract. 2017 Oct;20(10):8–9.

- Office of Dietary Supplements. Folate Fact Sheet for Health Professionals [Internet]. National Institutes of Healht; 2021 [cited 2021 Nov 8]. Available from: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Folate-HealthProfessional/

- Health Canada. Folic acid and neural tube defects [Internet]. Health Canada; 2018 [cited 2022 Sep 10]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/ services/pregnancy/folic-acid.html

- Douglas Wilson R, Van Mieghem T, Langlois S, Church P. Guideline No. 410: Prevention, Screening, Diagnosis, and Pregnancy Management for Fetal Neural Tube Defects. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2021 Jan;43(1):124-139.e8.

- Allen LH. How common is vitamin B-12 deficiency? Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Feb 1;89(2):693S-696S.

- Wolffenbuttel BHR, Muller Kobold AC, Sobczyńska‐Malefora A, Harrington DJ. Macro-B12 masking B12 deficiency. BMJ Case Rep. 2022 Jan;15(1):e247660.

- Lang T, Croal B. National minimum retesting intervals in pathology [Internet]. The Royal College of Pathologists; 2021 [cited 2022 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.rcpath.org/uploads/assets/253e8950-3721-4aa2-8ddd4bd94f73040e/g147_national-minimum_retesting_intervals_in_pathology.pdf

- Means R, Fairfield K. Treatment of vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies. Uptodate [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Jan 10]; Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-vitamin-b12-and-folate-deficiencies?sectionName=Treatment%20of%20vitamin%20B12%20 deficiency&search=vitamin%20b12%20deficiency%20gatric%20resection&topicRef=7155&anchor=H1540931056&source=see_link#H1540931056

Abbreviation

| H2 | Histamine |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency virus |

| IM | Intramuscular |

| NTDs | Neural tube defects N20 Nitrous oxide |

| PPI | Proton pump inhibitor |

| RBC | Red Blood cell |

Diagnostic code

Vitamin B12: 92450

Folate: 281.2

Associated Document

Practitioner Resources

- RACE: Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise Program – www.raceconnect.ca

RACE means timely telephone advice from specialist for Physicians, Medical Residents, Nurse Practitioners, Midwives, all in one phone call.

Monday to Friday 0800 – 1700

Online at www.raceapp.ca or though Apple or Android mobile device. For more information on how to download RACE mobile applications, please visit www.raceconnect.ca/race-app/

Local Calls: 604–696–2131 | Toll Free: 1–877–696–2131

For a complete list of current specialty services visit the Specialty Areas page.

- Pathways

- An online resource that allows GPs and nurse practitioners and their office staff to quickly access current and accurate referral information, including wait times and areas of expertise, for specialists and specialty clinics. See: https://pathwaysbc.ca/login

- Perinatal Services BC (PSBC) – www.perinatalservicesbc.ca

- Perinatal Services BC (PSBC) provides leadership, support, and coordination for the strategic planning of perinatal services in British Columbia and is the central source in the province for evidence-based perinatal information.

Patient, Family and Caregiver resources

- HealthLinkBC: HealthLinkBC provides reliable non-emergency health information and advice to patients in BC Information and advice in several languages is available by telephone, website, a mobile app and a collection of print resources. People

can speak to a health services navigator, registered dietitian, registered nurse, qualified exercise professional, or a pharmacist by calling 8-1-1 toll-free in BC or 7-1-1 for the deaf and hard of hearing.

- HealthLinkBC: Quick Nutrition Check for Vitamin B12

- HealthLinkBC: Vitamin B12 Deficiency Anemia

- HealthLinkBC: Getting Enough Folic Acid

- HealthLinkBC: Folate and Your Health

- HealthLinkBC: Folic Acid – Oral

- HealthLinkBC: Pregnancy and Nutrition: Folate and Preventing Neural Tube Defects

- HealthLinkBC: Folic Acid Test

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the effective date.

This guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee in collaboration with the Provincial Laboratory Medicine Services, and adopted under the Medical Services Act and the Laboratory Services Act.

For more information about how BC Guidelines are developed, refer to the GPAC Handbook available at

BCGuidelines.ca: GPAC Handbook.

THE GUIDELINES AND PROTOCOLS ADVISORY COMMITTEE

|

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

Contact Information: Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee PO Box Email: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca Disclaimer The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the “Guidelines”) have been developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The Guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The Guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional. |

TOP

TOP