22 - Vision impairments - CCMTA Medical Standards

Vision impairment and medical fitness to drive.

- 22.6.1 Impaired visual acuity – Non-commercial drivers

- 22.6.2 Impaired visual acuity – Commercial drivers

- 22.6.3 Visual field loss – Non-commercial drivers

- 22.6.4 Visual field loss – Commercial drivers

- 22.6.5 Loss of stereoscopic depth perception or monocularity – All drivers

- 22.6.6 Diplopia

- 22.6.7 Impaired colour vision

- 22.7.1 Visual acuity

- 22.7.2 Visual field

- 22.7.3 Contrast sensitivity

- 22.7.4 Examination of visual functions (EVF)

- 22.7.5 Visual field test (VFT)

22.1 About vision impairment

Vision impairment is defined as a functional limitation of the visual system and can be manifested as:

- Reduced visual acuity

- Reduced contrast sensitivity

- Visual field loss

- Loss of depth perception

- Diplopia (double-vision)

- Visual perceptual difficulties, or

- Any combination of the above

This chapter focuses on common vision impairments and medical conditions and treatments that can cause vision impairments.

Common vision impairments

Impaired visual acuity

Visual acuity is the ability of the eye to perceive details. It can be described as either static or dynamic. Static visual acuity, the common measure of visual acuity, is defined as the smallest detail that can be distinguished in a stationary, high contrast target (e.g. an eye chart with black letters on a white background). When tested, it is reported as the ratio between the test subject’s visual acuity and standard “normal” visual acuity.

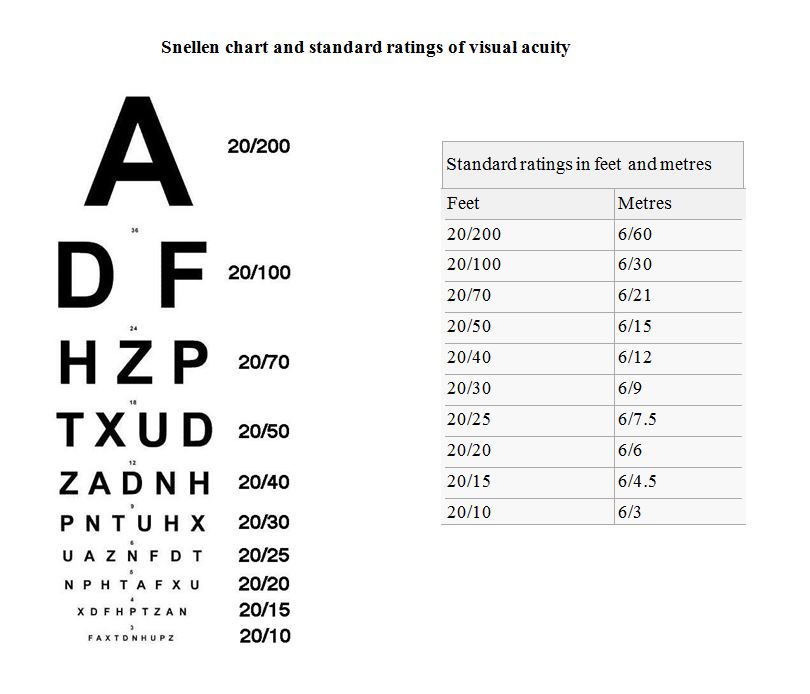

Normal visual acuity is described as 20/20 or 6/6 in metric. A person with 20/40 vision (6/12 metric) needs to be 20 feet (6 metres) away to distinguish detail that a person with normal vision can distinguish at 40 feet (12 metres). The standard Snellen chart for measuring visual acuity and a table of standard ratings is included in 22.7.1

Dynamic visual acuity is the ability to distinguish detail when there is relative motion between the object and the observer. Given the nature of driving, dynamic visual acuity would seem to be more relevant to licensing decisions than static visual acuity. However, barriers to the use of dynamic visual acuity for decision-making include:

- The absence of a practicable method of testing dynamic visual acuity

- Limited research on its relevancy for driving, and

- The lack of established levels of dynamic visual acuity required for driving safely

Myopia, hyperopia, presbyopia and astigmatism (refractive errors)

Myopia, hyperopia, presbyopia and astigmatism are conditions associated with reduced visual acuity. They are known as refractive errors and are the result of errors in the focusing of light by the eye.

Myopia (nearsightedness) is a condition in which near objects are seen clearly but distant objects do not come into proper focus. Individuals with normal daytime vision may experience “night myopia.” Night myopia is believed to be caused by pupils dilating to let more light in, which adds aberrations that result in nearsightedness. It is more common in younger individuals and people who are myopic.

Hyperopia (farsightedness) is a condition in which distant objects are seen clearly but close objects do not come into focus. Age-related farsightedness is called presbyopia. It is not a disease, but occurs as a natural part of the aging process of the eye and usually becomes noticeable as an individual enters their early to mid 40s.

Astigmatism is a visual condition that results in blurred vision. It commonly occurs with other conditions such as myopia and hyperopia.

Visual field loss

The visual field is the extent of the area that a person can see with their eyes held in a fixed position, usually measured in degrees. The normal binocular (using both eyes) visual field is 135 degrees vertically and 180 degrees horizontally from the fixed point.

The visual field can be divided into central and peripheral portions. Central vision refers to vision within 30 degrees of the point of fixation or gaze. The macula, a small area in the center of the retina, is responsible for fine, sharp, straight-ahead central vision.

Peripheral vision allows for the detection of objects and movement outside the scope of central vision.

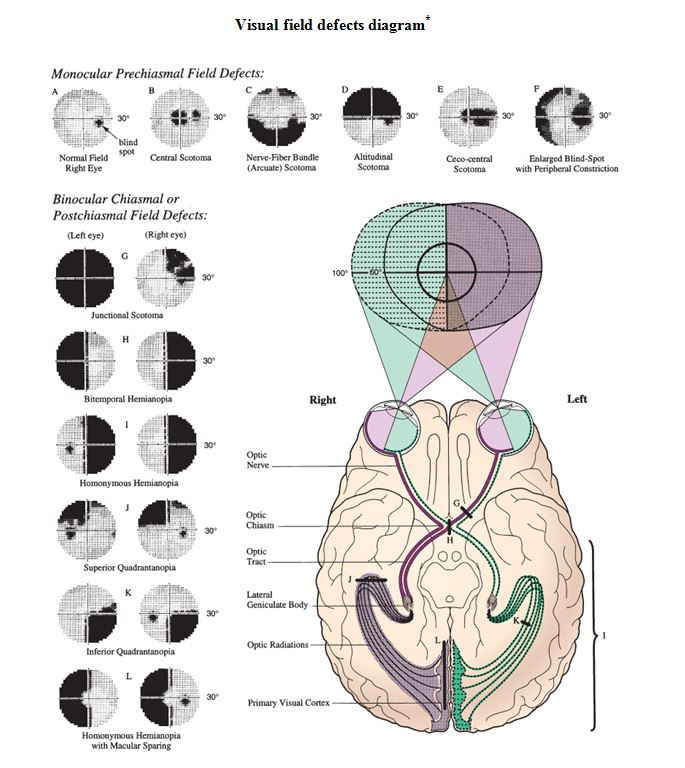

Visual field impairment refers to a loss of part of the normal visual field. The table and diagram on the following two pages provide further information on various types of visual field defects. The term “scotoma” refers to any area where the area of lost visual field is surrounded by normal vision.

Hemianopia, vision loss in one half of the visual field, or quadrantanopia, vision loss in one quarter of the visual field, can occur as a result of a stroke, trauma or tumour. They are not usually caused by a problem with the eye itself.

An important consideration related to hemianopia is the potential for anosognosia. Anosognosia is a condition in which a person with an impairment caused by a brain injury is unaware of the impairment. Research indicates that hemianopic anosognosia is relatively frequent, occurring in approximately two-thirds of those with hemianopia.

Unawareness of visual field deficits has an obvious negative impact on safe driving performance.

| Types of visual field defects* | ||

| Type | Description | Causes |

| Altitudinal field defect | Loss of all or part of the superior or inferior half of the visual field, but in no case does the defect cross the horizontal median |

More common: Ischemic optic neuropathy, hemibranch retinal artery occlusion, retinal detachment Less common: Glaucoma, optic nerve or chiasmal lesion, optic nerve coloboma |

| Arcuate scotoma | A small, arcuate-shaped field loss due to damage to the ganglion cells that feed into a particular part of the optic nerve head, which follows the arcuate shape of the nerve fibre pattern; the defect does not cross the horizontal median |

More common: Glaucoma Less common: Ischemic optic neuropathy (especially nonarteritic), optic disk drusen, high myopia |

|

Binasal field defect (uncommon) |

Loss of all or part of the medial half of both visual fields; the defect does not cross the vertical median |

More common: Glaucoma, bitemporal retinal disease (e.g. retinitis pigmentosa) Rare: Bilateral occipital disease, tumour or aneurysm compressing both optic nerves |

| Bitemporal hemianopia | Loss of all or part of the lateral half of both visual fields; the defect does not cross the vertical median |

More common: Chiasmal lesion (e.g. pituitary adenoma, meningioma, craniopharyngioma, aneurysm, glioma) Less common: Tilted optic disks Rare: Nasal retinitis pigmentosa |

| Blind-spot enlargement | Enlargement of the normal blind spot at the optic nerve head | Papilledema, optic nerve drusen, optic nerve coloboma, myelinated nerve fibres at the optic disk, drugs, myopic disk with a crescent |

| Central scotoma | A loss of visual function in the middle of the visual field, typically affecting the fovea centralis |

Macular disease, optic neuropathy (e.g. ischemic, Leber's hereditary, optic neuritis), optic atrophy (e.g. from tumour compressing the nerve, toxic/metabolic disease) Rare: Occipital cortex lesion |

| Homonymous hemianopia | Loss of part or all of the left half or right half of both visual fields; the defect does not cross the vertical median | Optic tract or lateral geniculate body lesion; temporal, parietal, or occipital lobe lesion of the brain (stroke and tumour more common; aneurysm and trauma less common). Migraine may cause a transient homonymous hemianopia |

| Constriction of the peripheral fields leaving only a small residual central field | Loss of the outer part of the entire visual field in one or both eyes |

Glaucoma, retinitis pigmentosa or some other peripheral retinal disorder, chronic papilledema after panretinal photocoagulation, central retinal artery occlusion with cilioretinal artery sparing, bilateral occipital lobe infarction with macular sparing, nonphysiologic vision loss, carcinoma-associated retinopathy Rare: drugs |

(*From https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/eye-disorders/approach-to-the-ophthalmologic-patient/evaluation-of-the-ophthalmologic-patient - Adapted from The Wills Eye Manual, Douglas J. Rhee, M.D. and Mark F. Pyfer, M.D.© 1999 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.)

(* Source National Eye Institute .)

Blindness/low vision

Total blindness is the complete lack of vision and is often described as no light perception. A person may be considered “blind” even though they have some vision. There is no universally accepted level of visual acuity to define blindness. In North America and most of Europe a person is considered to be legally blind if their visual acuity is 20/200 (6/60) or less in the better eye with the best correction possible, or if their visual field is less than 20 degrees in diameter. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines “low vision” as visual acuity between 20/60 (6/18) and 20/400 (6/120) or a visual field between 10 and 20 degrees in diameter. The WHO definition of “blindness” is visual acuity less than 20/400 (3/60) or a visual field less than 10 degrees.

Monocular vision/Loss of stereoscopic depth perception

Monocular vision refers to having vision in one eye only and is associated with the loss of stereoscopic vision. Stereoscopic vision, in which the brain processes information from each eye to create a single visual image, is integral to depth perception in those with binocular vision.

Impaired colour vision

Individuals with impaired colour vision (colour blindness) lack a perceptual sensitivity to some or all colours. These impairments are usually congenital and, in general, drivers learn to compensate for the inability to distinguish colours when driving.

Impaired contrast sensitivity

Visual contrast sensitivity refers to the ability to perceive differences between an object and its background. Depending on the cause, a loss of contrast sensitivity may or may not be associated with a corresponding loss of visual acuity. Declines in contrast sensitivity are associated with normal aging, and can also result from conditions such as:

- Cataracts

- Age-related macular degeneration

- Glaucoma, and

- Diabetic retinopathy

Impaired dark adaptation and glare recovery

Dark adaptation refers to the process in which the visual system adjusts to a change from a well-lit environment to a dark environment. Glare recovery refers to the process in which the eyes recover visual sensitivity following exposure to a source of glare, such as oncoming headlights when driving at night.

Prolonged dark adaptation is associated with normal aging and results in decreased visual acuity at night. It may also be the result of a medical condition, and where severe, may be referred to as “night blindness.” Night blindness may be caused by a number of medical conditions including:

- Retinitis pigmentosa

- Vitamin A deficiency

- Diabetes

- Cataracts, or

- Macular degeneration

As with dark adaptation, individuals require a longer time to recover from glare as they age. Cataracts and corneal edema are also associated with prolonged glare recovery.

Individuals may also experience prolonged glare recovery following laser assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) or panretinal laser photocoagulation (PRP) surgery.

A number of illnesses can affect glare recovery time, with prolonged recovery times reported in individuals with diabetes, vascular disease and hypertension. Retinal conditions with demonstrated relationships to prolonged glare recovery include age- related maculopathy, “cured” retinal detachment and central serous retinopathy.

Diplopia

Diplopia (double vision) is the simultaneous perception of two images of a single object. These images may be displaced horizontally, vertically or diagonally in relation to each other.

Diplopia can be binocular or monocular. Binocular diplopia is present only when both eyes are open, with the double vision disappearing if either eye is closed or covered.

Monocular diplopia is also present with both eyes open, but unlike binocular diplopia, the diplopia persists when the problematic eye is open and the other eye is closed or covered.

Binocular diplopia, or true diplopia, is an inability of the visual system to properly fuse the images viewed by each eye into a single image. It may be caused by the physical misalignment of the eyes (strabismus) or diseases such as Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis. Two of the most common causes of binocular diplopia in people over 50 are thyroid conditions, such as Grave’s disease, and cranial nerve damage.

Monocular diplopia is not caused by misalignment, but rather by problems in the eye itself. Astigmatism, dry eye, corneal distortion or scarring, vitreous abnormalities, cataracts and other conditions can cause monocular diplopia.

Nystagmus

Nystagmus is an involuntary, rapid, rhythmic movement of the eyeball. The movements may be horizontal, vertical, rotary or mixed. Nystagmus which occurs before 6 months of age is called congenital or early onset, whereas that occurring after 6 months is labelled acquired nystagmus. Early onset nystagmus may be inherited, or the result of eye or visual pathway defects. In many cases, the cause is unknown. Causes of acquired nystagmus are many and it may be a symptom of another condition such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, or even a blow to the head.

Many individuals with nystagmus have significant impairments in their vision, with some having low vision or legal blindness.

Medical conditions causing vision impairments

Cataracts

A cataract is an opacification or clouding of the crystalline lens of the eye, which blocks light from reaching the retina. Cataracts may be due to a variety of causes. Some are congenital, but few occur during the early years of life. The majority of cataracts are the result of the aging process. The presence of a cataract can interfere with visual functioning by decreasing acuity, contrast sensitivity and visual field.

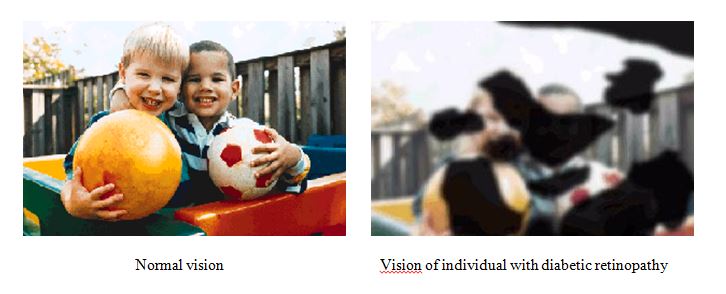

Diabetic retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy is the most common eye disease in those with diabetes, results in significant impairments in vision (blurred vision, vision loss) and is a leading cause of blindness in adults. It is caused by changes in the blood vessels of the retina (microvascular retinal changes) as a result of the disease.

There are two types of diabetic retinopathy: background (non-proliferative) and proliferative. Background retinopathy reflects early changes in the retina and often is asymptomatic. However, it may result in decreased visual acuity. Background diabetic retinopathy can progress into a more advanced or proliferative stage.

Proliferative retinopathy is the result of retinal hypoxia (lack of oxygen to the retina) and carries a much graver prognosis. The lack of oxygen to the retina results in a proliferation of new vessels in the retina or on the optic disc (neovascularization).

Without treatment, the new vessels can leak blood into the centre of the eye, resulting in blurred vision. Fluid (exudate) also can leak into the centre of the macula (that part of the eye where sharp, straight-ahead vision occurs), a condition called macular edema. The leakage causes swelling of the macula, resulting in blurred vision. Macular edema can occur at any stage of diabetic retinopathy, but is more likely to occur as the disease progresses. Research indicates that approximately half of those with proliferative retinopathy also have macular edema.

An example of the effects of diabetic retinopathy on vision is shown below*.

(*Source National Eye Institute - https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/diabetic-retinopathy)

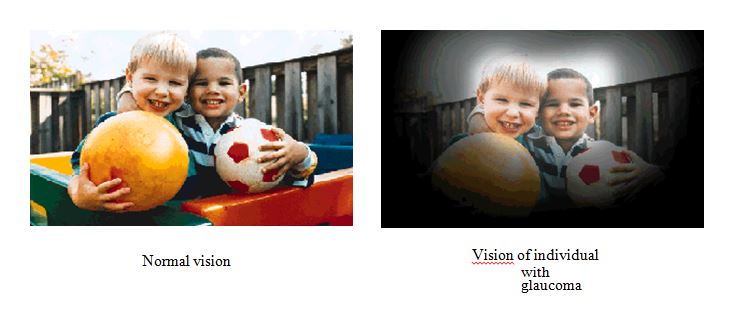

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a group of diseases characterized by increased intraocular pressure. The increased pressure can lead to optic nerve damage, resulting in blindness. Types of glaucoma include adult primary, secondary, congenital and absolute glaucoma. Open angle glaucoma, a type of adult primary glaucoma, is the most common. It is often referred to as the “silent blinder” because extensive damage may occur before the patient is aware of the disease. Early diagnosis and treatment are important for the prevention of optic nerve damage and visual field loss (primarily peripheral vision) due to glaucoma.

An example of the effects of glaucoma on vision is shown below*.

(*Source National Eye Institute - https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/glaucoma)

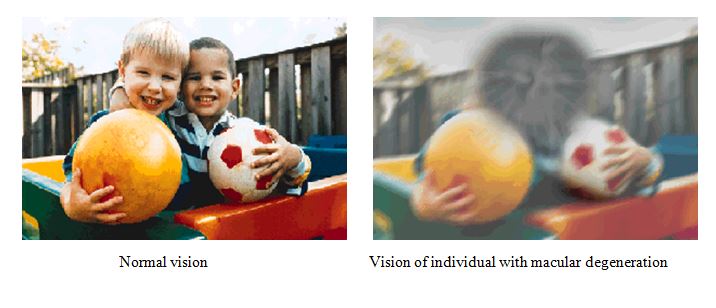

Age-related macular degeneration (ARMD)

Age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) is associated with the advanced stages of age-related maculopathy, or disease of the macula. The macula is the central portion of the retina and is responsible for central vision in the eye. Most individuals with maculopathy have impairments in their central vision. Those with ARMD, however, experience a progressive destruction of the photoreceptors in the macula, resulting in profound central vision loss.

ARMD has two forms, dry and wet. The dry form is the result of atrophy to the retinal pigment, resulting in vision loss due to the loss of photoreceptors (rods and cones) in the central portion of the eye. High doses of certain vitamins and minerals have been shown to slow the progression of the disease and reduce associated vision loss.

Wet ARMD (neovascular or exudative) is due to abnormal blood vessel growth in the eye, leading to blood and protein leakage in the macula. The bleeding, leaking and scarring from these blood vessels eventually result in damage to the photoreceptors, with a rapid loss of vision if left untreated. Treatment for wet ARMD has improved. Recent pharmaceutical advancements have resulted in compounds that, when injected directly into the vitreous humor, can cause regression of the abnormal blood vessels, leading to an improvement in vision.

An example of the effects of ARMD on vision is shown below*.

(*Source National Eye Institute - https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/resources-for-health-educators/eye-health-data-and-statistics/age-related-macular-degeneration-amd-data-and-statistics)

Retinitis pigmentosa

Retinitis pigmentosa is the term given to a group of hereditary retinal diseases that result in the degeneration of rod and cone photoreceptors. The diseases cause progressive visual loss, ending in blindness. Night blindness is an early symptom of retinitis pigmentosa, followed by a constriction of the peripheral visual field. Loss of central vision typically occurs late in the course of the illness.

Typically, symptoms are not prominent in childhood, but with progressive degeneration of the photoreceptor cells, vision is gradually lost during adolescence and adulthood.

22.2 Prevalence

Common vision impairments

Blindness/low vision

Based on WHO classifications, the prevalence of low vision and blindness in Canada is 35.6 and 3.8 per 10,000 individuals, respectively. Among individuals with some vision loss (vision worse than 20/40), cataract and visual pathway disease were the most common causes, together accounting for 40% of visual impairment. Age-related macular degeneration and other retinal diseases were the next most common causes of vision loss, with diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma less frequently encountered as causes of visual impairment.

Myopia, hyperopia, presbyopia and astigmatism (refractive errors)

The prevalence of visual conditions such as astigmatism, hyperopia, myopia and presbyopia in Canada is difficult to determine due to the absence of population based studies evaluating the ocular health of Canadians.

Night myopia is relatively common among younger individuals, with an estimated prevalence of 38% in those 16 to 25 years of age.

Monocular vision, impaired contrast sensitivity, impaired dark adaptation and glare recovery

There are no data on the prevalence of monocular vision, impaired contrast sensitivity or impaired dark adaptation and glare recovery.

Visual field loss including hemianopia

Research indicates that the prevalence of visual field loss for those age 16 to 60 years is between 3% and 3.5%, rising to 13% for those 65 and older.

Diplopia

There are no data on the prevalence of diplopia.

Nystagmus

Although the prevalence of nystagmus is not accurately known, the condition is believed to affect around 1 in 5,000 individuals.

Medical conditions causing vision impairments

Cataracts

Canadian data on the prevalence of cataracts are lacking, but statistics from the United States indicate that approximately 17% of Americans aged 40 years and older have a cataract on at least one eye. Cataracts frequently occur bilaterally (in both eyes), with the prevalence of bilateral cataracts greater among women than men. Overall prevalence of cataracts increases with age, leading to increasing prevalence in the future as the population ages. United States census estimates project that the prevalence of cataracts will increase by 50% by the year 2020.

Cataracts are more common in women and affect Caucasians somewhat more frequently than other races, particularly with advancing age. Risk factors for age-related cataracts include:

- Diabetes

- Prolonged exposure to sunlight

- Use of tobacco, and

- Use of alcohol

Diabetic retinopathy

Individuals with both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes are at-risk for diabetic retinopathy. At present there is little published information about the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in Canada. A study from the United States indicates that, after 20 years from the onset of diabetes, over 90% of people with Type 1 diabetes and more than 60% of people with Type 2 diabetes will have diabetic retinopathy.

Glaucoma

Approximately 67 million people worldwide have glaucoma, with more than 250,000 affected in Canada. Two percent of people over the age of 40 have glaucoma and the prevalence increases to 4% to 6% in people over 60. Those at increased risk for developing glaucoma include those over the age of 60 and individuals with a family history of glaucoma.

Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of blindness, accounting for between 9% and 12% of all cases of blindness. The rate of blindness from glaucoma is between 93 and 126 per 100,000 population 40 years or older.

Age-related macular degeneration (ARMD)

In Canada using 2010 data, more than two million people over the age of 50 have some form of ARMD, with the numbers projected to triple in the next 25 years due to the aging of the population. Dry ARMD is more common than wet ARMD, accounting for 85% of all cases of ARMD. The greatest risk factor for acquiring macular degeneration is age.

Retinitis pigmentosa

The worldwide prevalence of retinitis pigmentosa is approximately 1 in 4,000. Based on this prevalence rate, approximately 8,500 individuals in Canada currently suffer from retinitis pigmentosa.

22.3 Vision impairments and adverse driving outcomes

Common vision impairments

Impaired visual acuity

There is a considerable body of research examining the relationship between static visual acuity and driving performance. Despite the obvious importance of vision when driving, research has failed to find a strong relationship between the two. One of the primary reasons for this is methodological. Given that most jurisdictions have minimum vision requirements for licensing, individuals with significant vision impairments are not licensed and therefore not included in measures of driving performance.

Monocular vision

Research on monocular vision and driving is limited, with most studies conducted before 1980. The evidence suggests that monocular drivers have higher crash and traffic violation rates.

Impaired contrast sensitivity

In general, the available research suggests that impairments in contrast sensitivity are associated with impairments in driving performance. However, those associations are insufficient to support specific decisions regarding loss of contrast sensitivity and continued driving. More research is required to develop screening tools for contrast sensitivity that are valid and reliable in the driver fitness context.

Impaired dark adaptation and glare recovery

Despite its obvious relevance to safe driving performance, there is little in the way of research to assist the medical community or authorities in making decisions related to dark adaptation, glare recovery and driving.

Visual field loss including hemianopia

A significant body of literature now exists on the relationship between visual field loss and driving performance, as measured either by crashes, on-road performance or simulator studies. Few studies have been done on hemianopia and driving. Taken together, the results from the on-road and crash literature suggest that visual field deficits can and do compromise driving performance. However, the current body of evidence fails to inform on the extent of deficit in the visual field that must be present before driving is impaired.

Diplopia and Nystagmus

There is little or no research on diplopia or nystagmus and driving performance.

Medical conditions causing vision impairments

Cataracts

Results on the impact of cataracts on driving performance are mixed, with some studies showing increased risk of crashes, ranging from 1.3 to 2.5 times higher than those without cataracts. However, other studies have failed to find an association between cataracts and crash rates. Results from studies that have examined self-reported difficulties in driving performance are more uniform, with the majority of participants reporting difficulties in many aspects of driving.

Notably, cataract surgery results in an improvement in visual functioning. However, a significant percentage of drivers continue to report difficulties in driving, particularly at night. An important consideration is when driving can safely resume following cataract surgery. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of data to inform on this issue. Of equal importance are the effects of wait times for cataract surgery on visual functions related to driving. Current literature indicates that wait times of 6 months or longer result in decrements in vision that may have an impact on safe driving performance.

Diabetic retinopathy

The majority of research on diabetic retinopathy and driving is concerned with the effects of laser surgery (PRP) for proliferative diabetic retinopathy on visual fields. PRP reduces the risk of severe visual loss in proliferative diabetic retinopathy but also is associated with visual field loss and reductions in peripheral vision.

Glaucoma

There is evidence that drivers with glaucoma are at a significantly greater risk for impaired driving performance than those without the disease, likely due to loss of visual field.

Age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) and retinitis pigmentosa

There is little research on the relationship between ARMD or retinitis pigmentosa and driving performance.

2.4 Effect on functional ability to drive

| Condition | Type of driving impairment and assessment approach | Primary functional ability affected | Assessment tools |

| Vision impairment | Persistent impairment: Functional assessment | Sensory - Vision |

Medical assessments Visual assessment field test Functional assessment |

Drivers with impaired visual acuity may lack the ability to perceive necessary details while driving. Visual field impairments may interfere with driving by limiting the area that a driver can see.

Drivers with reduced contrast sensitivity may have difficulty seeing traffic lights or cars at night. Limitations in research and testing preclude standards for impairments in contrast sensitivity, dark adaptation or glare recovery, although some individuals with these impairments may not be able to drive safely.

22.5 Compensation

The loss of certain visual functions can be compensated for adequately, particularly in the case of long-standing or congenital impairments. When a person becomes visually impaired, the capacity to drive safely varies with the ability to compensate. As a result, there are people with visual deficits who do not meet the vision standards for driving but who are able to drive safely.

Corrective lenses

Most drivers can compensate for a typical loss of visual acuity from myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism or presbyopia by wearing eyeglasses or contact lenses.

Telescopic lenses/other low vision aids

Low vision and telescopic lens aids cannot be used to meet the vision standard.

Telescopic (bioptic) lenses are sometimes used to assist drivers with low vision. A telescopic lens typically is mounted at the top half of a regular spectacle lens, and provides the driver with a magnified view of objects (e.g. text or detail of traffic signs that otherwise could be seen only at distances too short for a safe or timely stop). For the most part, the driver views the road through the spectacle lens, looking intermittently through the telescopic lens to read road signs, determine the status of traffic lights or scan ahead for road hazards.

Although telescopic spectacles, hemianopia aids and other low vision aids may enhance visual function, there are significant problems associated with their use in driving a motor vehicle. These include the loss of visual field, magnification causing apparent motion and the illusion of nearness. There has been little research to evaluate the use of telescopic lenses for driving by drivers with low vision. Although limited, studies indicate that drivers with low vision who drive with telescopic lenses have higher crash rates.

Prism lenses/eye patch

Drivers with binocular diplopia may be able to compensate for their impairment with the use of prism lenses or an eye patch.

Driving in daylight only

Drivers who have a vision impairment may be able to compensate for their impairment by driving during daylight hours only.

Strategies to compensate for visual field loss

Drivers with visual field loss may be able to compensate for their reduced visual field by practicing more rigorous scanning techniques involving more frequent eye and head movement.

Exceptional Cases

The loss of some visual functions can be compensated for adequately, particularly in the case of long-standing or congenital impairments. When an individual becomes visually impaired, the capacity to drive safely varies with his/her compensatory abilities. As a result, there may be individuals with visual deficits who do not meet the vision standards for driving but who are able to drive safely. On the other hand, there may be individuals with milder deficits who do meet the vision standards but who cannot drive safely.

In these exceptional situations, it is recommended that the individual undergo a special assessment for the fitness to drive. The decision on fitness to drive can only be made by the appropriate licensing authorities. However, it is recommended the following information be taken into consideration: (1) favourable reports from the ophthalmologist or optometrist; (2) good driving record; (3) stability of the condition; (4) no other significant medical contraindications; (5) other references (e.g. professional, employment, etc); (6) functional assessment.

In some cases it may be reasonable to grant a restricted or conditional licence to an individual to ensure safe driving. It may also be appropriate to make such permits exclusive to a single class of vehicles.

22.6 Guidelines for assessment

22.6.1 Impaired visual acuity – Non-commercial drivers

| National Standard |

Non-commercial drivers eligible for a licence if:

|

| BC Guidelines |

|

| Conditions for maintaining licence | No conditions are required |

| Restrictions |

RoadSafetyBC will impose the following restriction on an individual who requires corrective lenses in order to meet the fitness guidelines

|

| Reassessment |

|

| Information from health care providers | Uncorrected and corrected standard rating of visual acuity for both eyes open, and examined together. Standards for testing visual acuity are outlined in 22.7.1 |

| Rationale | There is little research evidence regarding the level of visual acuity required for driving fitness. The minimum acuity requirement in the standard is based on consensus medical opinion in Canada. |

22.6.2 Impaired visual acuity – Commercial drivers

| National Standard |

|

| BC Guidelines |

|

| Conditions for maintaining licence | No conditions are required |

| Restrictions |

RoadSafetyBC will impose the following restriction on an individual who requires corrective lenses in order to meet the fitness guidelines:

|

| Reassessment |

|

| Information from health care providers | Uncorrected and corrected standard rating of visual acuity for both eyes open, and examined together. Standards for testing visual acuity are outlined in 22.7.1 |

| Rationale | There is little research evidence regarding the level of visual acuity required for driving fitness. The minimum acuity requirement in the standard is based on consensus medical opinion in Canada |

22.6.3 Visual field loss – Non-commercial drivers

| National Standard |

Non-commercial drivers eligible for a licence if:

|

| BC Guidelines |

|

| Conditions for maintaining licence | No conditions are required. |

| Reassessment |

|

| Information from health care providers | Binocular field print using an approved visual field testing technique. Standards for testing visual field loss are outlined in 22.7.2 |

| Rationale | There is little research evidence regarding the level of visual field required for driving fitness. The minimum visual field requirement in the standard is based on consensus medical opinion in Canada |

22.6.4 Visual field loss – Commercial drivers

| National Standard |

|

| BC Guidelines |

|

| Conditions for maintaining licence | No conditions are required |

| Reassessment |

|

| Information from health care providers | Binocular field print using an approved visual field testing technique. Standards for testing visual field loss are outlined in 22.7.2 |

| Rationale | There is little research evidence regarding the level of visual field required for driving fitness. The minimum visual field requirement in the standard is based on consensus medical opinion in Canada |

22.6.5 Loss of stereoscopic depth perception or monocularity – All drivers

| National Standard |

|

| BC Guidelines |

|

| Conditions for maintaining licence | No conditions are required |

| Reassessment |

RoadSafetyBC will not re-assess, other than routine commercial or age-related re-assessment |

| Information from health care providers |

|

| Rationale | Drivers with monocular vision can compensate for the loss of stereoscopic depth perception by using visual cues, such as the relative size of objects, and generally have adequate depth perception for everyday activities such as driving. The Canadian Ophthalmological Society notes that a driver who has recently lost the sight of an eye or stereoscopic vision may require a few months to recover the ability to judge distance accurately |

22.6.6 Diplopia

This guideline applies to drivers with diplopia within the central 40 degrees of primary gaze (i.e. 20 degrees to the left, right, above, and below fixation).

| National Standard |

|

| BC Guidelines |

|

| Conditions for maintaining licence | No conditions are required |

| Restrictions |

|

| Reassessment | If the diplopia is the result of a progressive condition, RoadSafetyBC will re-assess as recommended by the treating physician or in accordance with the re-assessment guidelines for that medical condition. Otherwise, no re-assessment, other than routine commercial or age-related re-assessment, is required |

| Information from health care providers |

|

| Rationale | Consensus medical opinion in Canada indicates that an individual who has diplopia within the central 40 degrees of primary gaze is not eligible for a licence unless they can compensate for this impairment by wearing an eye patch or prism lenses while driving. |

22.6.7 Impaired colour vision

| National Standard |

All drivers eligible for a licence if:

|

| BC Guidelines | RoadSafetyBC will not generally request further information |

| Conditions for maintaining licence | None |

| Reassessment | No re-assessment, other than routine commercial or age-related re-assessment, is required |

| Information from health care providers | Opinion of treating physician whether a lack of insight or cognitive impairment impairs the ability to compensate |

| Rationale | Impaired colour vision is usually congenital and in general, drivers learn to compensate for the inability to distinguish colours when driving |

22.7 Standards for testing visual functions

22.7.1 Visual acuity

The distance visual acuity of drivers should be tested using the refractive correction (spectacles or contact lenses) that they will use for driving. The examiner should assess visual acuity under binocular (both eyes open) conditions. It is recommended that visual acuity be assessed using a Snellen chart (see below) or equivalent at the distance appropriate for the chart under bright photopic lighting conditions of 275 to 375 lux (or greater than 80 candelas/m2). Charts that are designed to be used at 3 meters or greater are recommended.

22.7.2 Visual field

When a confrontational field assessment is carried out to screen for visual field defects the following procedure should be used at a minimum:

- The examiner is standing or seated approximately 0.6 m (2 feet) in front of the examinee with eyes at about the same level.

- The examiner asks the examinee to fixate on the nose of the examiner with both eyes open.

- The examiner extends his or her arms forward, positioning the hands halfway between the examinee and the examiner. With arms fully extended, the examiner asks the examinee to confirm when a moving finger is detected.

- The examiner should confirm that the ability to detect the moving finger is continuously present throughout the area specified in the applicable visual field standard. Testing is recommended in an area of at least 180° horizontal and 40° vertical, centred around fixation

If a defect is detected, the driver should be referred to an ophthalmologist or optometrist for a full assessment.

During a full visual field test, the following reporting formats are necessary:

1. All field tests must be binocular set at 150 (Class 1-4) or 120 (Class 5-8) continuous degrees along the horizontal meridian

2. Kinetic perimetry must be plotted at III4e isopters

3. Static perimetry must:

- Be in grid format clearly showing points seen and not seen OR numeric grid format showing absolute defects (<10 decibels)

- Not be shaded or coloured

- Not be expanded

Please note: No other reporting formats are acceptable

22.7.3 Contrast sensitivity

Assessment of contrast sensitivity is recommended for applicants referred to an ophthalmologist or optometrist for vision problems related to driving. Contrast sensitivity may be a more valuable indicator of visual performance in driving than Snellen acuity. The Canadian Ophthalmological Society therefore encourages increased use of this test as a supplement to visual acuity assessment.

Contrast sensitivity can be measured by means of several commercially available instruments:

- The Pelli-Robson letter contrast sensitivity chart

- Either the 25% or the 11% Regan low-contrast acuity chart

- The Bailey-Lovie low-contrast acuity chart, or

- The VisTech contrast sensitivity test

The testing procedures and conditions recommended for the specific test used should be followed.

22.7.4 Examination of visual functions form (EVF)

22.7.5 Visual field test form (VFT)