Osteoporosis: Diagnosis, Treatment and Fracture Prevention

Effective Date: May 1, 2011

Revised: October 1, 2012

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Step 1: Assessment of Risks of Osteoporosis or Fracture

- Step 2: Risk Stratification

- Step 3: Lifestyle Advice (Regardless of Risk Level)

- Step 4: Therapy

- Step 5: Monitoring

- Patient Education

- References

- Resources

- Abbreviations

- Appendices

Scope

Osteoporosis (OP) is a significant risk factor for fragility fracture. This guideline summarizes current recommendations for risk estimation, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of osteoporosis and related fractures in a general adult population (age 19+ years).

Diagnostic Code: 733.0: Osteoporosis

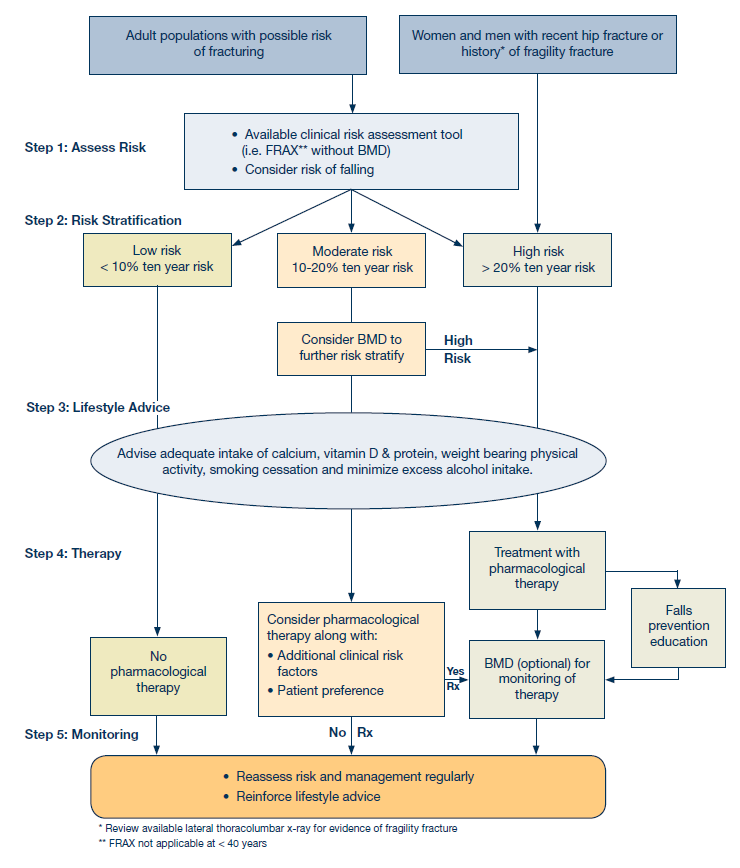

The following steps are outlined in this guideline (See Algorithm 1):

- Assessment of Risk

- Risk Stratification

- Lifestyle Advice (regardless of risk level)

- Therapy

- Monitoring

Step 1: Assessment of Risks of Osteoporosis or Fracture

There are two aspects of risk that can be explored by identifying known risk factors:

- Risk of developing OP (Section 1.1); and

- Risk of fracture within 10 years (Section 1.2).

1.1 Risk of developing osteoporosis

|

Family history |

Parental history of hip facture |

|

Medical history |

|

|

For men |

|

|

For women |

|

|

Lifestyle |

|

* See Frailty in Older Adults – Early Identification and Management for definition

** i.e., ≥ 3 months (consecutive) therapy at a dose of prednisone ≥ 7.5 mg per day or equivalent

1.2 Calculate the 10-year fragility fracture risk

The fracture risk of a patient can be estimated as Low (< 10% in next 10 years), Moderate (10 - 20% in next 10 years), or High (> 20% in next 10 years) using known risk factors and a clinical assessment tool. There are two tools available to calculate 10-year fracture risk. One is the FRAX® (see Appendix C [PDF, 382KB]), developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), and the other is produced by the Canadian Association of Radiologists and Osteoporosis Canada (CAROC). 1-3

FRAX®* employs a web-based (www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX) calculator that includes a number of risk factors; including bone mineral density (BMD) which is optional. The CAROC paper-based risk table takes into account age, sex, fracture history and glucocorticoid use to determine a ten-year absolute risk of all osteoporotic fractures but BMD is required to calculate risk.

*Although the FRAX® tool has been developed for prognosis and is not prescriptive, this guideline suggests the use of a tool to identify all risk groups for whom treatment will depend on individual clinical parameters and specific therapeutic indications listed in Steps 3 and 4 (e.g., age, previous vertebral fracture, T score, where appropriate).

1.3 Falls and the risk of fracture (also see “Falls prevention strategies” in Section 4.1)

Over and above the risk of OP, other clinical factors predict those at increased risk of fracture, including:4

Previous fragility fracture:

- Fractures sustained in falls from standing height or less, in which bone damage is disproportional to the degree of trauma. Includes vertebral compression fractures not attributable to previous major trauma, which may be suggested by height loss.

- Where other disease has been ruled out, patients with low trauma fragility fractures may have OP and are at high risk of other fragility fractures within 10 years.

- Fractures of the hip, vertebra, humerus, and wrist are most closely associated with OP and increased future fracture risk whereas those of the skull, fingers, toes, and patella fractures are not.

A fall in the last year

High risk of falling as determined by:

- Physical frailty or significant weight loss (loss of muscle mass). Refer to Frailty in Older Adults – Early Identification and Management

- A global assessment of functional mobility like the timed ‘Up and Go’ test5

- Poor strength

- Balance problems

- Gait problems

- Dizziness

- Poor vision

- Psychotropic medications

- Cardiac insufficiency

- Urinary frequency and toileting issues

- Other validated tests6

Algorithm 1: Recommendations for evaluation and management of osteoporotic and fragility fracture risk

Step 2: Risk Stratification

2.1 Levels of risk

Fracture risk estimation, using known risk factors and a clinical assessment tool, can be used to categorize patients as Low (< 10% in next 10 years), Moderate (10 – 20% in next 10 years) or High (> 20% in 10 years) fracture risk.

2.2 Risk stratification using Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (DXA) BMD

BMD is not indicated unless patients (men and women) are age > 65 years, at moderate risk of fracture (10 - 20% 10-year risk), and results are likely to alter patient care.7,8,9 There has been a shift away from BMD and towards emphasizing multivariate fracture risk using a risk calculation model (FRAX® or CAROC). BMD is not recommended to be used alone as it explains only a portion of fracture risk. If a clinical risk assessment tool suggests moderate fracture risk category, consider BMD testing to further stratify risk and guide treatment; if high risk, consider treatment.

BMD is NOT indicated for:

- Investigation of chronic back pain

- Investigation of exaggerated dorsal kyphosis (fractures are best excluded by radiography)

- Screening women aged < 65 years, unless significant clinical risk factors have been identified

- Part of a routine evaluation around the time of menopause

- Confirmation of OP when a fragility fracture occurs

T-score classification (number of standard deviations above or below the mean peak BMD):6

- Normal: T is -1 and above

- Osteopenia: T is -1.1 to -2.4

- Osteoporosis: T -2.5 and below

- Established or severe OP: T is -2.5 or below and one or more prevalent low-trauma fractures

DXA is a quantitative test and it requires careful quality assurance. Structural abnormalities, positioning, artifacts (e.g., body weight), and analysis can significantly affect results.9

2.3 Laboratory testing (bone turnover markers and vitamin D)

Indications: Blood tests are not indicated to make an OP diagnosis or determine risk. Blood tests are only useful to establish or to rule out secondary causes of OP. Refer to Appendix B - Testing for Suspected Secondary Causes of OP in Selected Patients (PDF, 211KB).

Bone turnover markers: At present no single or combined assay is recommended except in specific circumstances.10Assays have a proven use in research studies involving large samples but they are complex and variation is too great to be useful at the individual level.

Vitamin D: Routine testing is not required to diagnose OP or before/after starting vitamin D supplementation. Refer to Vitamin D Testing Protocol.

Step 3: Lifestyle Advice (Regardless of Risk Level)

Nutrition: Help reduce fracture risk via adequate daily calcium and vitamin D. Note: doses recommended below for calcium and vitamin D represent total intake from diet and supplements.

- Calcium: Recommend 1000-1200 mg elemental calcium per day including supplements, if necessary.11-13 See OP Patient Guide (PDF, 269KB). Advise patients not to exceed recommended amounts, as evidence does not support higher doses of calcium supplementation.14 In addition, a 2010 meta-analysis reported an increase in myocardial infarction in men and women given calcium supplementation (i.e., ≥ 500 mg elemental calcium per day) versus placebo. Note: this meta-analysis studied calcium supplementation alone and not in combination with vitamin D and the increased risk was associated with dietary intakes of greater than 800 mg (approximately) elemental calcium per day.15

- Vitamin D: Recommend 800-1000 IU per day of vitamin D3, including supplements if necessary, to adults over the age of 50.17 Higher doses (i.e., 2000 IU per day) may be needed in some cases and are considered safe.16 See Patient Guide (PDF, 269KB) and Vitamin D Testing Protocol.

- Protein: Recommend an adequate intake of dietary protein (1g/kg/day).21

Exercise: Regular weight-bearing and muscle-strengthening reduce the risk of falls and fractures by improving agility, strength, posture, and balance, as well as general health benefit.

Smoking: Tobacco products are detrimental to the skeleton as well as to overall health.

Alcohol: Intake of 3 or more units (5oz wine, 1.5oz spirits, 12oz beer) per day is detrimental to bone health and increases the risk of falling.

Step 4: Therapy

4.1 Falls prevention strategies

Falls prevention is the first line of treatment (versus OP medications) for those at high risk for falling.

Items to identify falls risk and reduce falls (review with patient at least annually)

- Ask about falls in the past year

- Assess the time taken to stand from sitting

- Assess muscle strength, balance, and gait by watching the patient walk and move

- Check and correct postural hypotension and cardiac arrhythmias

- Evaluate any neurological problems

- Review prescription meds that may affect balance

- Provide a checklist for improving safety at home, i.e., The Safe Living Guide-A Guide to Home Safety for Seniors, www.phac-aspc.gc.ca

Consider referral to geriatric medicine, a falls prevention program, homecare, occupational therapy or physical therapy.

4.2 Pharmacological therapy

(See also Appendix D - Prescription Medication Table for Osteoporosis [PDF, 277KB])

Medications may be recommended, depending on fracture risk assessment. Manage based on degree of risk:

Section 4.1: Items to identify falls risk and reduce falls (review with patient at least annually)

Low risk: Generally require lifestyle advice and daily intake of calcium and vitamin D.22

Moderate risk: Medication is usually not necessary but can be considered in addition to lifestyle advice and adequate daily intake of calcium and vitamin D. When considering medications, take into account patient preference and additional clinical risk factors (Table 3).22

Additional clinical risk factors:

- Vertebral fractures (> 25% height loss with end-plate disruption)

- Men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer

- Women receiving aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer

- Long-term or repeated systemic corticosteroid use (oral or parenteral) that does not meet the conventional criteria for recent prolonged systemic corticosteroid use (i.e., ≥ 3 months consecutive) therapy at a dose of prednisone ≥ 7.5 mg per day or equivalent)

- Recurrent falls

Consider referral to geriatric medicine, a falls prevention program, homecare, occupational therapy or physical therapy.

High risk: Consider medication in addition to lifestyle advice and adequate daily intake of calcium and vitamin D.23 Patients with hip and other fragility fractures are considered to be high risk. Individuals can be considered as candidates for medication after implementing fall prevention strategies and providing lifestyle advice (see Step 3).

OP medications available in Canada include (alphabetically): alendronate, calcitonin, denosumab, estrogens (with or without progesterone), etidronate, raloxifene, risedronate, teriparatide, and zoledronic acid.23 Data are insufficient to determine if one drug class is superior to another for fracture prevention.22 Medication adherence (compliance and persistence) is required for fracture reduction, yet rates of adherence to OP treatments are low.24

- Consider barriers to adherence including mode of administration, dosing regimens, side effects, and cost (see Appendix D - Prescription Medication Table for Osteoporosis [PDF, 277KB]).

- Combine adequate calcium and vitamin D with all pharmacological treatments. (See Step 3)

For information regarding PharmaCare coverage of these medications please refer to Appendix D (PDF, 277KB).

4.2.1 Bisphosphonates

These drugs preserve bone by decreasing rate of bone turnover and enhancing bone mineralization. 22,23,25,26,30 To date, this class of drugs (specifically alendronate, risedronate, and zoledronic acid) has the largest body of randomized controlled trial evidence for osteoporosis. Superiority of one bisphosphonate over another has not been conclusively shown. Most studies have been in post-menopausal women and the optimal duration of therapy is unknown (to date most studies, with fractures as an endpoint, have had an average five years duration).

|

Bisphosphonates |

Points to consider |

|

Alendronate (oral) |

|

|

Etidronate (oral) |

|

|

Zoledronic acid (intravenous) |

|

4.2.2 Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators [SERMs]: Raloxifene

SERMs can act as estrogen agonists or antagonists. Raloxifene acts as an estrogen agonist on bone tissue. The estrogenic effects of raloxifene on bone in postmenopausal women decrease bone turnover. 22,25,26,35

|

Drug |

Points to consider |

|

Raloxifene (oral) |

|

4.2.3 RANK Ligand Inhibitor: Denosumab

Denosumab is an injectable monoclonal antibody to the receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB ligand (RANKL). It inhibits bone resorption by osteoclasts by blocking the interaction between RANKL and its receptor RANK on the surface of osteoblasts.35,39,40

|

Drug |

Points to consider |

|

Denosumab |

|

4.2.4 Synthetic Parathyroid Hormone: Teriparatide

Teriparatide is an anabolic agent that improves bone quality, quantity, and increases bone strength. 22-24,30,36

|

Drug |

Points to consider |

|

Teriparatide |

|

4.2.5 Calcitonin Peptides: Calcitonin Salmon

Calcitonin Salmon is an inhibitor of bone resorption; available in parenteral and nasal spray formulations. Although calcitonin does not build bone, in women > 5 years beyond menopause, it appears to slow bone loss and increase spinal bone density. 26,37,38

|

Drug |

Points to consider |

|

Calcitonin (nasal) |

|

4.2.6 Hormone Replacement Therapy [HRT] (estrogen with or without progesterone)

HRT is primarily indicated for the management of moderate to severe menopausal symptoms in women. 22,24-26,35 A beneficial effect has been seen on BMD and fracture risk due to the significant anti-resorptive activity of estrogen.

|

Drug |

Points to consider |

|

HRT (oral or transdermal) |

|

Step 5: Monitoring

5.1 Clinical re-assessment

Re-assess patients as clinically indicated to monitor side effects, compliance, height loss, incident fractures, and risk of falls, which may alter patient management.

5.2 Follow-up BMD measurements

There is insufficient evidence to recommend a testing frequency for patients not taking OP medications. Based on a patient’s risk profile, BMD retesting may be indicated in 3-10 years.

For patients on OP medication, repeat BMD examinations are not justified based on current evidence. If a BMD is to be done, any changes would be difficult to detect prior to 3 years.41 Consider more frequent testing in specific high risk situations (e.g., multiple risk factors, or receiving ≥ 7.5 mg prednisone daily or its equivalent for 3 months consecutively who require a baseline examination and repeat scans at 6-month intervals while on treatment).

Women > 65 years will usually lose bone. A stable BMD value on treatment may reflect successful treatment and appreciable decreases in fracture risk may accompany minor increases in BMD. Minor increases in BMD may also be due to testing variance. Ideally, any follow-up BMD testing is recommended to be done on the same DXA machine and at the same time of year.

Patient Education

A patient guide to OP (PDF, 296KB) is included with this guideline. Further information for patients about OP is available at Health Link BC (www.healthlinkbc.ca).

References

- Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, et al. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(4):385-97.

- Kanis JA, Compston J, Cooper A, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men from the age of 50 years in the UK. Maturitas. 2009 Feb 20;62(2):105-8.

- Siminoski K, Leslie WD, Frame H, et al. Recommendations for bone mineral density reporting in Canada. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2005 June;56(3):178-88.

- Papaioannou A, Joseph L, Ioannidis G, et al. Risk factors associated with incident clinical vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women: the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos). Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(5):568-78.

- Podsiadlo, D, Richardson, S. The timed ‘Up and Go’ test: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000 Jan;48(1):104-5.

- Lord SR, Menz HB, Tiedemann A. A physiological profile approach to falls risk assessment and prevention. Phys Ther. 2003;83(3):237-52.

- National Osteoporosis Foundation, Clinician's guide to the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis, c2008 [updated 2010 Jan.; cited April 1, 2010]. Available from: https://www.bonehealthandosteoporosis.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/995.pdf

- Osteoporosis: review of the evidence for prevention, diagnosis and treatment and cost-effectiveness analysis. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8 Suppl 4:S7-80.

- Khan AA, Brown JP, Kendler DL, et al. The 2002 Canadian bone densitometry recommendations: take-home messages. CMAJ. 2002 Nov;12;167(10):1141-5.

- Garnero P, Mulleman D, Munoz F, et al. Long-term variability of markers of bone turnover in postmenopausal women and implications for their clinical use: the OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res. 2003 Oct;18(10):1789-94.

- Health Canada. Dietary reference intakes: reference values for elements. C2005 [cited March 1, 2011]. Available from: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/nutrition/reference/table/ref_elements_tbl-eng.php

- Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Canada. Bone Health. JOGC. 2009;31:S34-41.

- National Institute of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. C2010 [cited June 11, 2010]. Available from:http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/calcium.asp.

- Tang B, Eslick G, Nowson C, et al. Use of calcium or calcium in combination with vitamin D supplementation to prevent fracture and bone loss in people aged 50 years and older: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2007;370:657-66.

- Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Baron JA, et al. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;341:c3691

- Vieth R. Vitamin D toxicity, policy and science. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:S2;V64-V68.

- Hanley DA, Cranney A, Jones G, et al. Vitamin D in adult health and disease: a review and guideline statement from Osteoporosis Canada. CMAJ. 2010 Jul 19. [Epub ahead of print]

- Institute of Medicine. Vitamin D. In: Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1997; p.250-87.

- Briot K, Audran M, Cortet B, et al. Vitamin D: skeletal and extra skeletal effects; recommendations for good practice. Presse Med. 2009;38:43-54.

- Cranney A, Horsley T, O’Donnell S, et al. Effectiveness and safety of vitamin D in relation to bone health. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2007 Aug;(158):1-235. Review.

- Hannan MT, Tucker KL, Dawson-Hughes B, et al. Effect of dietary protein on bone loss in elderly men and women: The Framingham Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(12):2504-12.

- MacLean C, Newberry S, Maglione M, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of treatments to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:197-213.

- Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties: The Canadian Drug Reference for Health Professionals. Toronto, Ontario;2010.

- Stroup J, Kane M, Abu-Baker A. Therapy Update: Teriparatide in the treatment of osteoporosis. Am J Health-Sys Pharm. 2008;65(6):532-9.

- Marcus R, Wong M, Heath H III, et al. Antiresorptive treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: comparison of study designs and outcomes in large clinical trials with fracture as an endpoint. Endocr Rev. 2002:23:16-37.

- Reid R, Blake J, Abramson B, et al. Menopause and osteoporosis update 2009. JOGC. 2009;31(Supp 1):S1-49. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/journal-of-obstetrics-and-gynaecology-canada/vol/31/issue/1/suppl/S1

- Orwoll E, Ettinger M, Weiss S, et al. Alendronate for the treatment of osteoporosis in men. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:604-610.

- Ringe JD, Faber H, Dorst A. Alendronate treatment of established primary osteoporosis in men: Results of a 2-year prospective study. J of Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5252-5255.

- Adachi JD, Bensen WG, Brown J, et al. Intermittent etidronate therapy to prevent corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:382-387.

- Boucher M, Murphy G, Coyle D, et al. Bisphosphonates and teriparatide for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women [Technology overview no 22]. 2006. Ottawa, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.

- Alendronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Wells, George A. Cranney, Ann. Peterson, Joan. Boucher, Michel. Shea, Beverley. Welch, Vivian. Coyle, Doug. Tugwell, Peter. Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2, 2011.

- Risedronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Wells, George A. Cranney, Ann. Peterson, Joan. Boucher, Michel. Shea, Beverley. Welch, Vivian. Coyle, Doug. Tugwell, Peter. Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4, 2010.

- Etidronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Wells, George A. Cranney, Ann. Peterson, Joan. Boucher, Michel. Shea, Beverley. Welch, Vivian. Coyle, Doug. Tugwell, Peter. Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4, 2010.

- Intravenous zoledronate for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Albergaria, Ben-Hur. Gomes Silva, Brenda Nazare. Atallah, Alvaro N. Fernandes Moca Trevisani, Virginia. Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1, 2009.

- The North American Menopause Society: NAMS Continuing medical education activity; Management of Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women: 2010 Position Statement 2010;17(1):23-56. Available from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/714984

- Orwoll E, Scheele WH, Paul S, et al. The effect of teriparatide [human parathyroid hormone (1-34)] therapy on bone density in men with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(1):9-17.

- Ishida Y, Kawai S. Comparative efficacy of hormone replacement therapy, etidronate, calcitonin, alfacalcidol, and vitamin K in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: The Yamaguchi Osteoporosis Prevention Study. Am J Med. 2004;117:549-55.

- Tóth E, Csupor E, Mészáros S, et al. The effect of intranasal salmon calcitonin therapy on bone mineral density in idiopathic male osteoporosis without vertebral fractures – an open label study. Bone. 2005;36:47-51.

- Reid IR, Miller PD, Brown JP, et al. Effects of denosumab on bone histomorphometry: the FREEDOM and STAND studies. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;10:2256-65.

- Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(8):756-65.

- Compston J. Monitoring osteoporosis treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009 Dec;23:781-8.

Resources

- BC Guidelines: Clinical Practice Guidelines

- BC Seniors Health Care Support Line, 1-877 952-3181, and website www.seniorsbc.ca/healthcare

- Injury Prevention and Mobility Laboratory, Simon Fraser University www.sfu.ca/ipml

- Centre for Hip Health and Mobility, University of British Columbia www.hiphealth.ca

Abbreviations

|

BMD |

bone mineral density |

|

BMI |

body mass index |

|

DXA |

dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry |

|

FDA |

Food & Drug Administration (U.S.A) |

|

GIO |

glucocorticoid induced osteoporosis |

|

HRT |

hormone replacement therapy |

|

IU |

international units |

|

OP |

osteoporosis |

Appendices

Appendix A - Examples of Medications that May Contribute to Bone Loss (PDF, 211KB)

Appendix B - Testing for Suspected Secondary Causes of OP in Selected Patients (PDF, 211KB)

Appendix C - Using the FRAX® Calculator to Assess Absolute Fracture Risk (PDF, 362KB)

Appendix D - Pharmacological Therapy for Osteoporosis (PDF, 227KB)

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the Effective Date.

This guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, approved by the British Columbia Medical Association and adopted by the Medical Services Commission.

|

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

|

Disclaimer The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the "Guidelines") have been developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The Guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The Guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problems. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional.

TOP

TOP